When the House was busy negotiating its Obamacare repeal bill this spring, conservative Republicans said they had one—and pretty much only one—goal for the legislation: It had to bring down insurance premiums. Period.

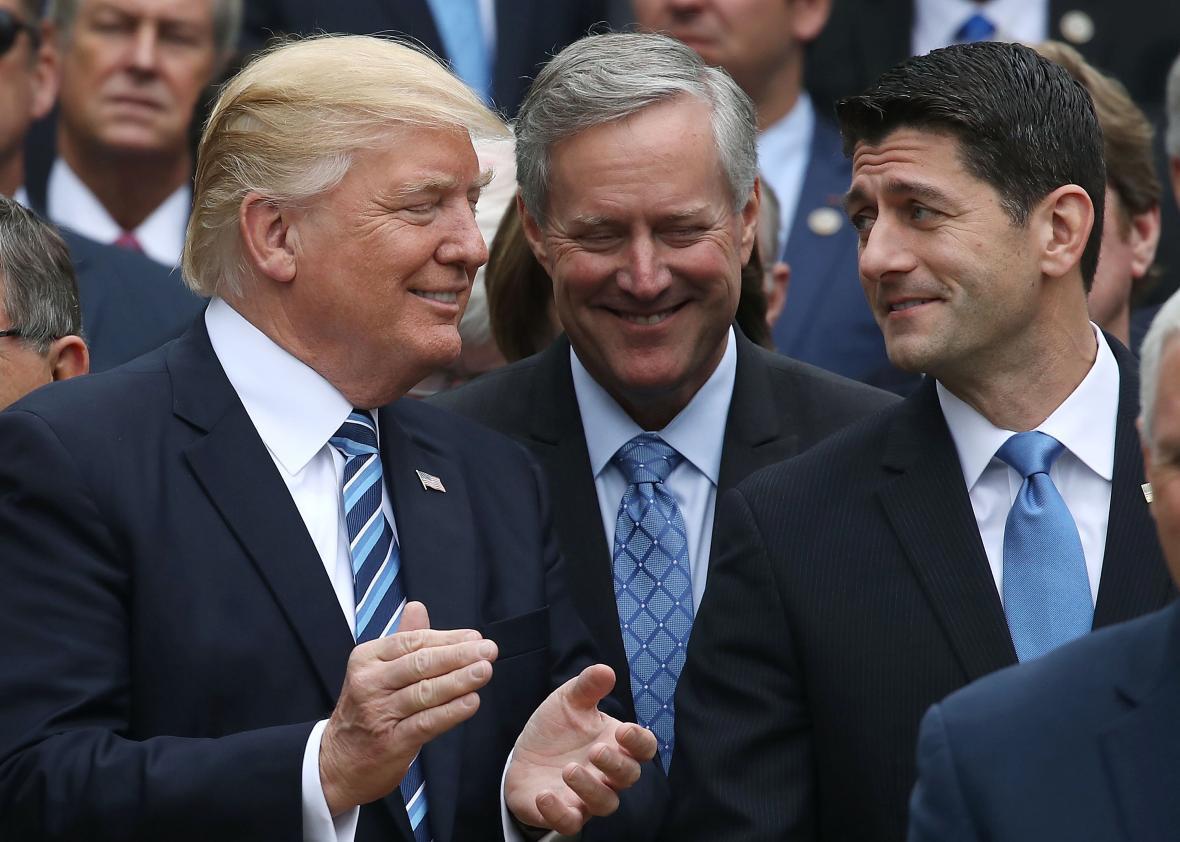

“I can tell you that there is one score that the American people will pay attention to,” Mark Meadows, chairman of the hard-line House Freedom Caucus, said in March, after the first draft of the law emerged. “And that is, does it really lower their health care costs and their premiums? That’s the only score that really matters. And if this doesn’t do it, then we need to make sure that we find something that does do it.”

Meadows and the Freedom Caucus of course threw their support behind the American Health Care Act in May, after negotiating a number of concessions they said would lower the cost of insurance. “Actually, it drives down premiums,” the North Carolina representative said on Morning Joe, adding that, “The first bill that came out actually had an increase in premiums in the short term.” In fact, there wasn’t any obvious way Meadows could have known what the bill would do at the time, since the Congressional Budget Office hadn’t scored it yet. But the CBO’s forecast eventually bore out his point: Though some people, particularly older Americans, would see the cost of insurance rise astronomically, the office concluded that by 2026, average premiums would fall across the states.

So, mission accomplished?

Nope. Not at all. It seems the CBO report left out something important: the value of government subsidies. Today, Obamacare provides tax credits to lower- and middle-income families in order to make coverage more affordable. The House bill provides tax credits, too, but they would be less generous for many households, because they’re based on age rather than income. Because the CBO only tried to forecast premiums before tax credits in its analysis, it didn’t actually tell us whether families would be paying more or less on average for their insurance.

Turns out they might be paying more. On Tuesday, the Office of the Actuary at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services released its own score of the House bill. It finds that gross premiums—that is, before tax credits kick in—would fall 13 percent by 2026. However net premiums—that is, after tax credits—would rise 5 percent, because the law’s subsidies would simply be worth less. What’s more, average out-of-pocket costs like deductibles and co-pays would skyrocket 61 percent, in large part because the law ends the Obamacare rules that limit those expenses for poorer families. Overall, people will simply be paying more for their coverage and care ($162 a month more, on average, to be precise).

Of course, the actuary’s estimates rely on a number of assumptions. For instance, it guesses that only a quarter of states will choose to waive Obamacare’s insurance market regulations, such as the requirements that insurers cover certain essential medical services, as the American Health Care Act would allow them to. It’s very possible that more states would take that opportunity, which could drop premiums lower.

These are also only average effects. In the end, the House bill will mean different things for different Americans. Premiums before subsidies will go down for younger, healthy customers and way up for people in their 60s, because the AHCA increases the amount insurers can charge older enrollees compared to people in their twenties. If states waive the Essential Health Benefits rules, people who need more services (like women who want childbirth coverage) will pay a lot more for them. Some upper-middle-class households that were never eligible for Obamacare’s subsidies could come out ahead, meanwhile, because they would qualify for the House bill’s tax credits.

Finally, it’s very likely that the Senate will change the House bill’s subsidy structure, and possibly make it more generous—though that would take more money.

But don’t let that obscure the greater point. Conservatives said their bill would bring down the cost of insurance for families. This estimate says it’s entirely possible that, overall, it won’t. If that’s the case, the ACHA fails at its one and only job.