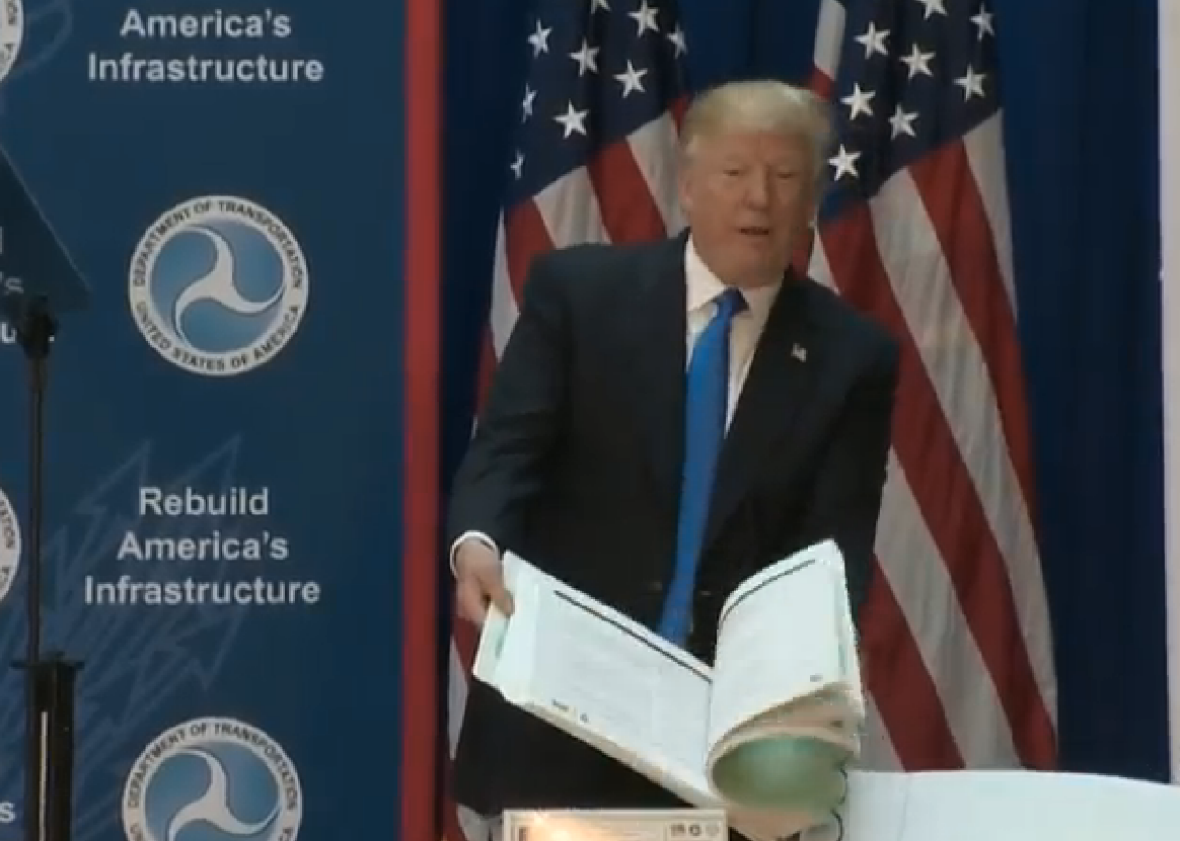

In a speech on Friday dedicated to speeding up infrastructure construction, President Trump couldn’t resist deploying one of his favorite props: a big stack of paper.

This time, the paper was the 10,000-page environmental report for the Intercounty Connector, an 18-mile highway in Maryland, enclosed in three binders that the president borrowed from a state highway official to demonstrate the waste and folly of federal bureaucracy.

Denouncing the report as “nonsense,” Trump unceremoniously dropped the binders on the floor, to applause, before kicking them out of the way as he returned to the lectern. “Nobody’s going to read it, except the consultants who get a fortune for this,” the president said. “These binders could be replaced by just a few simple pages, it would be just as good. It would be much better.”

The Intercounty Connector, or MD-200, is a $2.4 billion, 18-mile highway that was first proposed more than 50 years ago but not completed until 2014. Supporters of this tolled alternative to the Beltway, which slices through suburbs and wetlands parallel to the Washington ring road, have condemned its opponents as tree-huggers standing in the way of progress.

But with exaggerated traffic estimates furnished by consultants, the predictions for toll revenue failed to come true: Vehicle counts were 20 percent lower than what consultants had predicted. Revenue was one-third the low-end prediction. It’s true that environmentalists battled the road in court for years, delaying it and raising the construction costs. But they also got the size of the highway reduced from 12 lanes to six.

Imagine if the ICC had been twice the size. As it is, Maryland had to raise tolls on other crossings to pay off ICC debt. The ICC only passed its year-one toll revenue estimate in its third year of operation. Around that time, Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan canceled Baltimore’s Red Line project and shifted the state’s $1.35 billion contribution into highway funding instead, a decision that prompted an investigation from President Obama’s Department of Transportation.

The ICC is slowly filling up, because new highways always do. They don’t solve traffic congestion. But they do create more car-dependent lives, stemming from new personal choices and new car-dependent patterns of housing and employment. Or as the California Department of Transportation put it in a recent paper, “Increasing Highway Capacity Unlikely to Relieve Traffic Congestion.”

As a symbol, then, the ICC represents the overwhelming influence of the highway construction lobby—more than the obstructionism of environmental activists.

Trump was announcing the creation of a new office in the Council of Environmental Quality dedicated to rooting out inefficiency, clarifying lines of authority, and streamlining coordination between different levels of government.

The president bemoaned, as he has before, the glacial pace of public works construction in the United States, and spoke wistfully of the Hoover Dam and the Golden Gate Bridge, built in five and four years, respectively.

Could U.S. infrastructure be built more quickly? Yes. Is 10,000 pages too many pages for an 18-mile highway? Yes. And yet, according to a Congressional Research Service review of the subject, environmental reports prompted by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) are mostly a scapegoat. “Causes of delay,” the CRS reports, “are more often tied to local/state and project-specific factors, primarily local/state agency priorities, project funding levels, local opposition to a project, project complexity, or late changes in project scope.” And while phony environmental concerns are used as a pretext to forestall growth of all kinds, the bias in highways is definitively towards building.

But hey, the trade-offs involved in expediting the construction of public works are difficult. And dropping binders on the floor is easy. And fun.