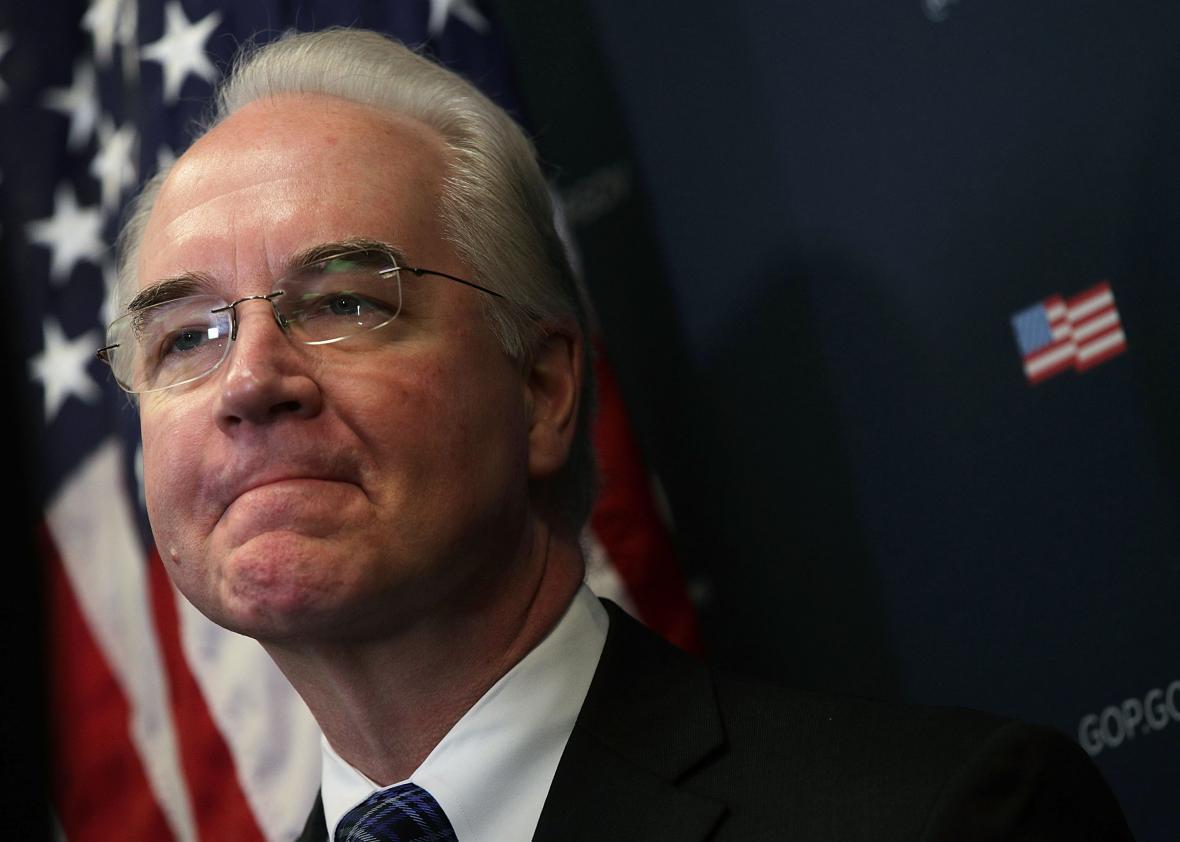

One of Tom Price’s go-to criticisms of the Affordable Care Act is that it does not, in fact, provide people much in the way of care. The law has helped many Americans obtain insurance, sure. But because the policies have such high deductibles, he argues, patients still can’t afford medical help. “People have coverage, but they don’t have care,” the Health and Human Services secretary likes to say.

Other members of the Trump administration parroted Price’s line as they tried, and failed, to sell their health reform bill to a skeptical public and Congress this month. But it turns out the hand-waving about coverage vs. care wasn’t just futile: It was also plain wrong. A new study released this week by the National Bureau of Economic Research suggests that, contrary to the White House’s utterly ineffectual talking points, Obamacare really has delivered on its promise of helping Americans get to the doctor.

Wound. Meet salt.

Previous papers have explored how Obamacare expanded insurance coverage, and some have examined the way the law’s Medicaid expansion affected measures of people’s actual health, like how well Americans say they feel in surveys. The new study, which is still only in early draft form, tries to look at the effects of the whole ACA on both health access and outcomes through 2015—while untangling the impact of Medicaid from the law’s changes to the individual insurance market. Their findings are based on an analysis of data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, a large annual health survey conducted by states and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.1

As a whole, the paper finds, Obamacare’s impact on access has been very positive. The results “imply that the full ACA reduced the uninsured rate by 44 percent while also reducing the number of people without a primary care doctor by 12 percent, those with foregone care because of cost by 28 percent, and those not having an annual checkup by 10 percent,” the authors write. It wasn’t just the ACA’s Medicaid expansion that’s made this happen. “The results suggest that the private portion of the ACA”—meaning the market regulations and exchanges where customers buy subsidized insurance—“increased access to care along all observable dimensions,” including whether people had coverage, had a doctor, or had a physical.

So, according to these draft results at least, Obamacare increased both coverage and access to care, which in a more rational world would force Price to find a new spiel. (Don’t count on it.) Where the law disappointed somewhat was outcomes. With the exception of older people who lived in states that expanded Medicaid, the researchers did not find evidence that Obamacare led Americans overall to self-report better health. It also didn’t find any signs that people’s body mass indexes dropped, or that people smoked or drank less after the insurance expansion.

Now, one might argue that two years is an incredibly short period of time in which to improve the average health of an entire, notoriously sedentary nation. But at Bloomberg View, Megan McArdle suggests that these results should make people at least question the value of expanding insurance. She points to another famous study from Oregon which found that although people reported better health after gaining coverage through Medicaid, their personal health stats like blood pressure, cholesterol, or blood sugar failed to improve. She writes:

It turns out the link between “health care” and “health” is not as close as we would like. Health insurance is not magic. Insurance can give you access to a doctor, but it cannot make you take your medicine. An absolutely astonishing percentage of people don’t take their hypertension medication, even though the side effects are minimal, the medications are cheap generics, and the benefits are large; overall, about 50 percent of patients seem to fail to take their medicine as recommended. Insurance cannot make you stop drinking or smoking or overeating. Just ask the primary-care physicians charged with bullying people out of those behaviors.

All of this may be true. But, as McArdle concedes, the balance of evidence suggests that increasing health coverage does save lives—and living people are generally healthier than the dead. Beyond that, I’m not sure how many would argue that improving health outcomes is the single most important goal of expanding insurance coverage. Many people, seemingly including Republicans like Price, believe that people ought to be able to get access to health care without bankrupting themselves just because it makes them happier and more secure in their lives. Some might even say that being able to access a doctor without emptying your savings should be a right, even if it doesn’t lead people to stub out their cigarettes. And on that front, things like the Medicaid expansion seem to have been wildly successful. As you might expect, giving people insurance coverage tends to reduce medical debt and make it easier for people to pay their doctors’ bills (and, perhaps partly for that reason, seems to make them less depressed). Shielding the vulnerable from financial hardship is a perfectly reasonable use of public money.

This week gave us evidence Affordable Care Act has done just what it promised, by making care affordable. For that alone, it’s worth celebrating—and defending once the GOP works up the nerve to again try to gut it.

1 For those interested in the methodology: The economists looked at the relationship between uninsured rates in different parts of the country before Obamacare’s implementation, and how trends in health access and outcomes evolved in those places after the law took effect. They’re essentially working from two assumptions: First, places with higher uninsured rates had more to gain from the ACA. Second, there shouldn’t be any systemic correlation between a city’s uninsured rate in 2013 and the change in the likelihood that people had a primary care doctor over the next two years, unless Obamacare was at play. (Of course, they also include all kinds of controls for demographics and such.)