Fifty years after passage of laws meant to break down barriers to racial integration, segregation in the American city persists.

And it has a cost. A new analysis by the Urban Institute, in collaboration with Chicago’s Metropolitan Planning Council, models how economic indicators in the country’s hundred largest commuting zones (a proxy for metropolitan areas) vary according to racial and economic segregation.

Using data from the 1990, 2000, and 2010 U.S. census, the researchers found that economic and racial segregation are correlated with bad outcomes not only for segregated groups, but for regions as a whole. In doing so, they make the case that racial and economic segregation—as much as the crime rate, median household income, and the prevalence of college degrees—should be a concerted focus of local, state, and federal leaders.

“We find that higher levels of economic segregation are associated with lower incomes, particularly for black residents,” they write. “Further, higher levels of racial segregation are associated with lower incomes for blacks, lower educational attainment for whites and blacks, and lower levels of safety for all area residents.” We know how covenants, redlining, and racial violence kept black families from building home equity, the central factor in the racial wealth gap. Now we’re learning how segregation drags down important economic indicators for entire regions.

The focus is on Chicago. Ranked in a “composite segregation index” that examines where people live by income and race, the Chicago area ranks fifth in the country in segregation, behind Philadelphia, Bridgeport, New York City, and Milwaukee. (Those are older cities, but 20th-century cities like Los Angeles, Houston, Nashville, and Miami are not far behind. The problem is broad.)

Racial and economic segregation in Chicagoland is dropping, but at this rate, it could take another half-century to reach the median for urban areas. If it happened today, they reckon, the effects would be dramatic. Desegregation to the U.S. median in Chicago would:

- increase black per capita income 12.4 percent

- increase both white and black ranks of college grads by 83,000

- drop the homicide rate by 30 percent

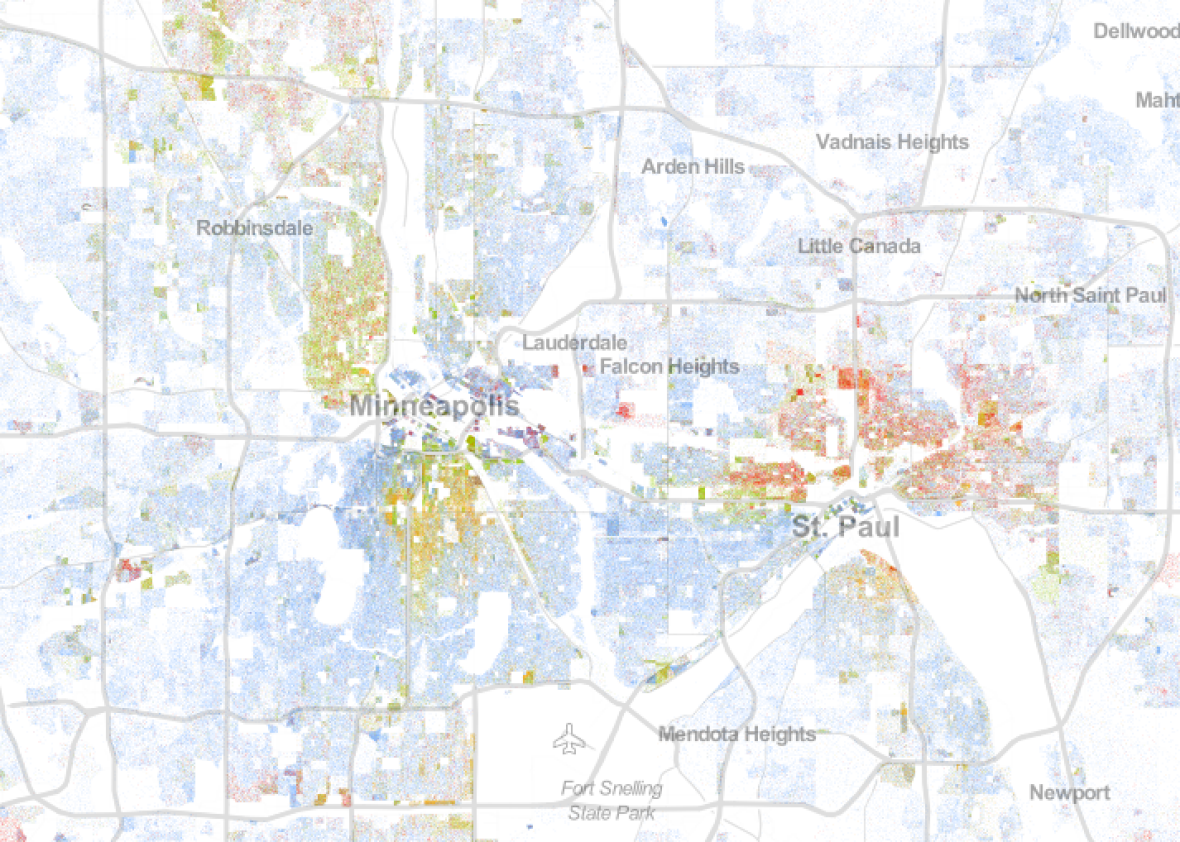

Those figures probably underestimate the consequences of segregated settlement patterns, since the U.S. median looks like Minneapolis:

Racial dot map

The research seems particularly relevant right now, as Ben Carson settles in as chief administrator of the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Toward the end of the Obama administration, HUD Secretary Julian Castro adopted a new desegregation rule called Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing, which asks local jurisdictions to assess barriers to fair housing in their own communities—and deal with them.

In his only published statement on housing policy prior to his confirmation hearing, Carson trashed the rule. During his hearing, he sounded more open to its enforcement.

Some ex-Obama staffers are optimistic. “I think there’s a strong bias to do this on a regional basis,” former Obama HUD official Harriet Tregoning told me last month. “You could call this about fair housing, but we could call it about workforce development—the same systemic barriers to access show up.”

Jake Blumgart, writing earlier this month in Slate, found that the rule appeared to be gaining traction despite mixed signals from Washington:

Many of the early affected counties and cities, it turned out, were ready for a federal nudge. As many jurisdictions become more racially diverse, progressive politicians at the local level are more open to pressure from advocates on housing issues than they used to be. “We are seeing a number of jurisdictions that have already affirmed their commitment to fair housing regardless of whether the rule is removed,” says Laurel Blatchford, a former HUD chief of staff and now the chief program officer with Enterprise Community Partners, a nonprofit that’s assisted jurisdictions in complying with AFFH.

When the moral imperative fails to move the needle, maybe economic modeling can help.