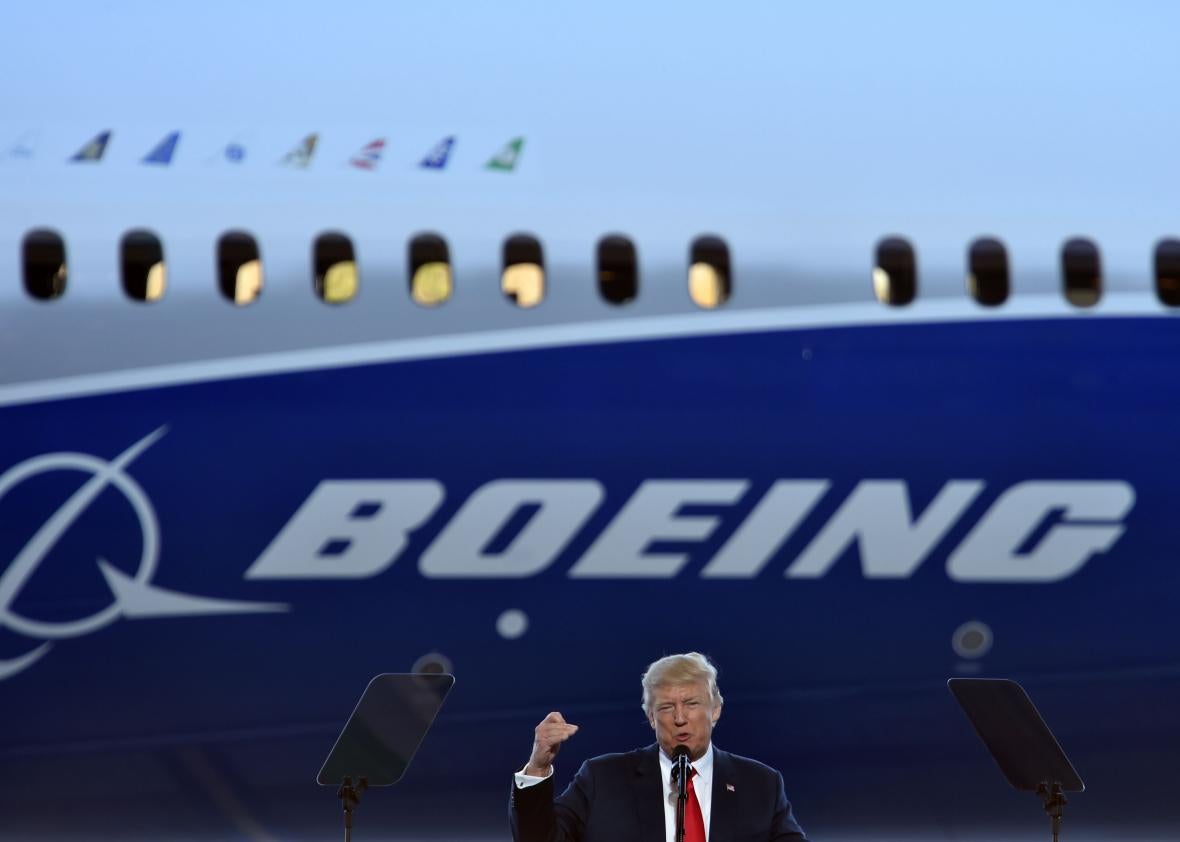

The corporate tax breaks you tend to hear about are the outliers: Tesla’s $1.3 billion from Nevada, Boeing’s $8.7 billion from Washington state, Mike Pence’s deal to keep some Carrier jobs in Indiana.

Less flashy but more important, a February report from the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research suggests, are the run-of-the-mill economic development incentives built into state law across the country and designed either to attract companies, to keep them in place, or to get them to add positions. In 2015, incentives for new or expanding export-based industries (i.e., manufacturing, tech, media, any company that sells its goods or services beyond the local economy) offset average state and local business taxes by 30 percent, costing the U.S. $45 billion.

The report, based on a database of 26 years of incentives in 33 states, affirms the consensus that these tax breaks—which have tripled since 1990, when the database begins keeping track—don’t do much to convince companies to move. Plotting the effects of incentives and taxes on state GDP growth, the study concludes their effects are “always statistically insignificant … the maximum possible effects of incentives on increasing growth … are towards the lower end of the range of estimates in the previous literature.” (And the literature, as Richard Florida reminds us at City Lab, does not smile on incentives.) And that null hypothesis seems to hold true even within the industries where the incentives were applied.

“There’s big disparity in incentives across even adjacent states,” explained Timothy Bartik, a senior economist at Upjohn and the author of the report. Incentives can vary by as much as 3 to 1 across state lines, and there’s little evidence they exert a strong effect on corporate geography, said Bartik, or respond to in-state economic trends. “The largest predictor of whether a state is offering a lot of incentive deals is whether they offered them the year before.” In other words: States don’t offer these deals to companies because they need to, but because it’s simply what they already do.

Tax breaks, as you might expect, make more political than economic sense. The biggest growth in corporate handouts has been in job creation tax credits, or JCTCs—these account for about two-thirds of total incentive growth in 1990. The premise is simple: Company creates jobs, company saves on taxes. That looks good for pols, who can provide new jobs immediately but defer revenue shortfalls until the next guy’s administration. (Short-term deals are more likely to make companies move, but also produce a quicker impact on the budget.)

One problem with the job fetish is that incentives have tended to go toward low-wage businesses, and offer little reward for wage increases:

For example, the regressions suggest that a 10 percent increase in wages increases incentives by a little under 3 percent. But the potential social benefits from higher industry wages probably go up by significantly more than 3 percent for a 10 percent higher wage.

Higher wage jobs aren’t just better for the people that have them, they also have a higher “multiplier effect”—a worker with a higher wage will go out to dinner more often, sustaining another local job. And so on. But they aren’t well-targeted by the rewards that states offer.

At the end of the day, Bartik says, states may have better, more creative options than just offering cash for jobs, like offering companies customized job training or manufacturing extension services (local hubs that help manufacturers with all manner of business problems). Incentive as a service, in other words. It’s not only that customized job training, for example, may be more cost-effective in encouraging job growth. It’s also that if the company in question is lured away by another state’s tax break, you’re left with a trained workforce instead of an empty factory.