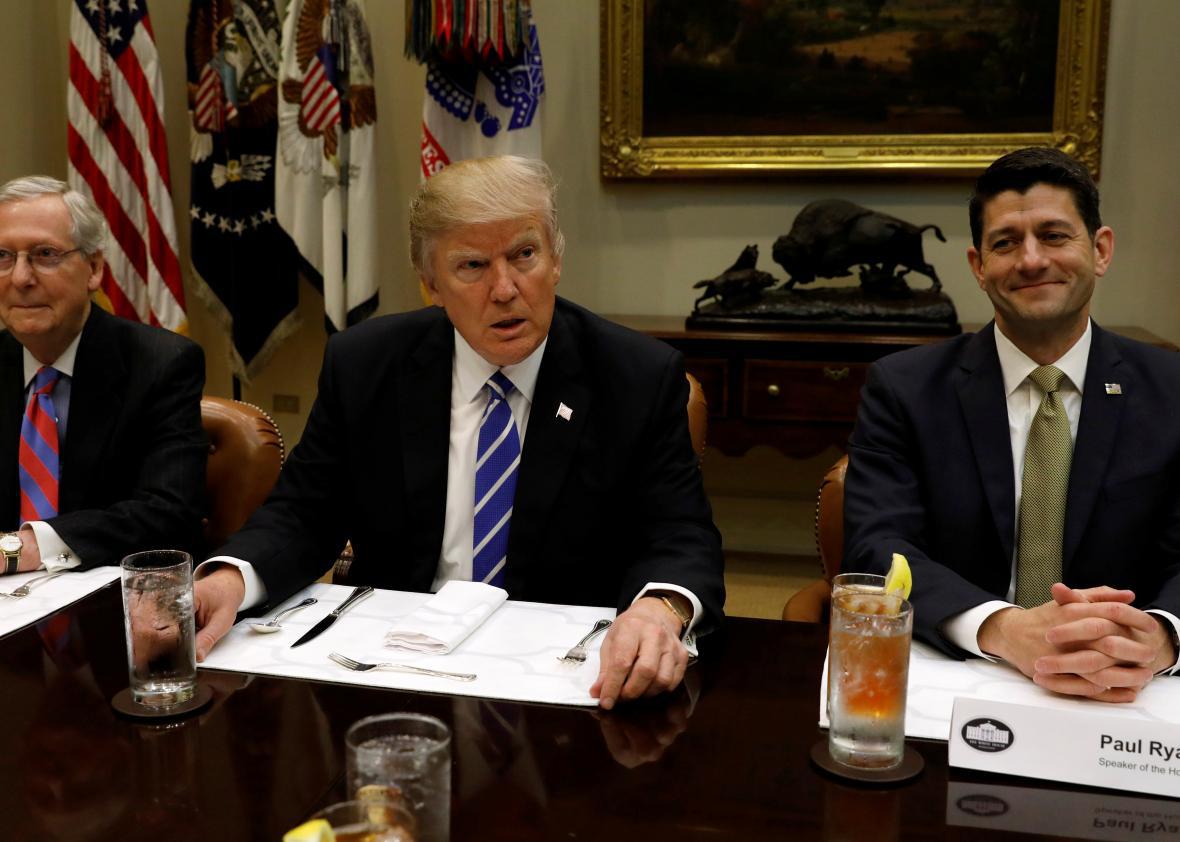

Republicans have argued for months—for years, even!—that the Affordable Care Act is a disaster that must be repealed immediately to save the health insurance markets from imminent collapse. House Speaker Paul Ryan has been a particularly eager prophet of doom, suggesting on many recent occasions that the law’s insurance exchanges were in the middle of a death spiral. “We are on a rescue mission to prevent Obamacare from making things even worse,” he said in January.

On Monday, after stalling for six or so years, Ryan and the House GOP finally released their official plan to replace the ACA. In a lot of ways, it feels like the punchline to a slow-boiling joke. When it comes to the individual market, the legislation looks an awful lot like Obamacare, but with stingier benefits and weaker incentives that could exacerbate the very problems that Republicans claim they are trying to fix. It’s as if they’re trying to repair a flat tire by stabbing it with jackknife.

Obamacare has often been described as a three-legged stool. First, it bars insurance companies from discriminating against patients with pre-existing conditions—meaning carriers can’t reject customers or charge them extra just because they have melanoma or a weird allergy history. While these rules are extremely popular, they would be a disaster on their own. Americans would just wait until they were sick to buy a health plan, and insurers would bleed money, a problem known as adverse selection. That’s why the ACA’s architects created the individual mandate—leg two—which requires adults to purchase coverage every year or pay a tax penalty. That way, in theory, young people can’t just opportunistically buy coverage when they need it, and the healthy help pay for the sick. Finally, the law also provides subsidies that help lower-income families pay their premiums, putting the affordable in the “Affordable Care Act.”

So far, Obamacare’s three legs have been a little wobbly. The biggest weak point has always been that, in spite of the mandate, insurers haven’t been able to attract enough youngish, healthy customers to make up for the number of older, iller patients they are required to cover by law. As a result, many companies have retreated from the individual insurance markets created by the ACA after losing a great deal of money insuring a sicker customer base than they expected. There are nearly 1,000 U.S. counties with just one insurer offering coverage now, up from 182 in 2016. The losses have also led companies to hike premiums and deductibles, a constant source of frustration among voters, many of whom feel like they’re paying for insurance they can’t use. Ryan, for his part, has suggested that the entire Affordable Care Act may be facing an adverse-selection death spiral, where rising premiums driven by sick patients eventually cause the whole market to shrink and crumble. That may or may not actually be happening—if anything, it may have been hastened by the uncertainty created by Donald Trump’s presidential win and his saber-rattling about Obamacare repeal—but it’s one of the main arguments for repeal.

So how are Ryan & co. planning to rescue the markets, which they believe are facing imminent peril? By making it easier for Americans to opt out of buying insurance, of course. The Republican replacement plan would still protect patients with pre-existing conditions from discrimination. But it wouldn’t force healthy Americans to buy coverage in order to subsidize the sick, à la the individual mandate. Instead, it includes a sort of half-baked “continuous coverage” rule. If Americans go more than 63 days without a health plan, the next time they sign up during open enrollment their insurer will be allowed to charge them 30 percent extra for one year. After that, they’ll be charged the same as everybody else in their age and market.

In the grand scheme of carrots and sticks, that’s basically a twig. Young, healthy people who weren’t spurred on to buy insurance by the individual mandate almost certainly aren’t going to be herded into the market by the threat of paying a somewhat higher premium down the line. If anything, knowing that they’ll face a surcharge might encourage them to hold off until the last minute.

“The late enrollment penalty may encourage relatively healthy but older or slightly higher risk folks to sign up,” Caroline Pearson, senior vice president of policy and strategy at health consultant Avalere, told me in an email.* “Basically, people who don’t have immediate health needs but do periodically consume health care services will be more likely to maintain continuous coverage. However, young and healthy individuals who very rarely see a doctor may continue to sit out of the market, even for minor health needs. They would probably wait until they had a serious health care need and then sign up for coverage and pay the penalty.”

The GOP’s legislation does include a vague backup plan in the form of “market stabilization grants,” which are meant to help states cover the cost of insuring particularly high-cost patients. But it’s not clear how much good that would do if young people simply stay on the sidelines as sick patients sign up for coverage. “I think there’s a real risk that this produces a less stable individual insurance market than the ACA,” Kasier Family Foundation senior vice president Larry Levitt told me in an email.

This all seems even more bizarre when you consider that the Republican plan would wind up cutting insurance subsidies to many young adults, possibly giving them even more reason not to buy coverage. That’s because instead of targeting financial help at lower-income households who need the most assistance, as Obamacare does, the GOP legislation offers tax credits to help buy coverage that are only based on age, at least until they start phasing out for individuals that make $75,000 or more a year. Americans younger than 30 would be eligible for a $2,000 credit, significantly less than what many poorer twentysomethings qualify for now.

Republicans might argue that, by eliminating and loosening Obamacare’s various insurance market regulations, their bill will push the cost of insurance so low that young people will be able to buy coverage for nothing but the cost of the tax credit. But it’s far from clear that legislation would actually succeed at that goal. Even if it did, it wouldn’t entirely solve the problem of adverse selection. Insurers would instead be encouraged to offer cheap and profitable catastrophic coverage aimed at the young rather than more substantial health plans favored by the old and sick.

The odd thing here is that Republicans are very much aware of just how important the individual mandate is to making the pre-existing conditions rules work. After all, they spent years attacking it through lawsuits in order to fatally undermine Obamacare, until Supreme Court Justice John Roberts shut them down. So why would they balance their own health reform effort on this bizarre, watered-down version?

There are really two answers. The first is politics. The public likes the ACA’s pre-existing conditions rules. Town halls have filled up with voters testifying about how the regulations saved their lives, and lawmakers don’t want to be blamed for kicking cancer patients to the curb. At the same time, the public deeply dislikes the individual mandate, which conservatives have spent years arguing is an assault on basic American liberties. And so the GOP has little choice but to do something, no matter how ill-conceived that something might be.

Republicans’ hands are also tied thanks to the arcane procedural rules of the Senate. The party only controls 52 seats in the chamber, not enough to pass legislation over a Democratic filibuster. To skirt that roadblock, Republicans are planning to use a special process known as reconciliation, which can only be used to deal with budget matters. Unfortunately for them, that means they can’t amend regulations, like the protections for pre-existing conditions, even if they wanted to. It’s also unclear whether the continuous-coverage rule they’ve proposed would pass muster, but they may just be desperate.

Republicans have backed themselves into a political corner where they are trying to keep the parts of Obamacare everybody likes while jettisoning the nasty but necessary parts responsible for making the popular pieces work as well as they do. There’s a good chance the end result will resemble the kind of chaos we’ve seen in Obamacare’s least successful markets.

The GOP says it’s on a rescue mission. Republicans may end up shooting the wounded instead.

*Correction, March 7, 2017: This post originally misspelled Caroline Pearson’s last name.