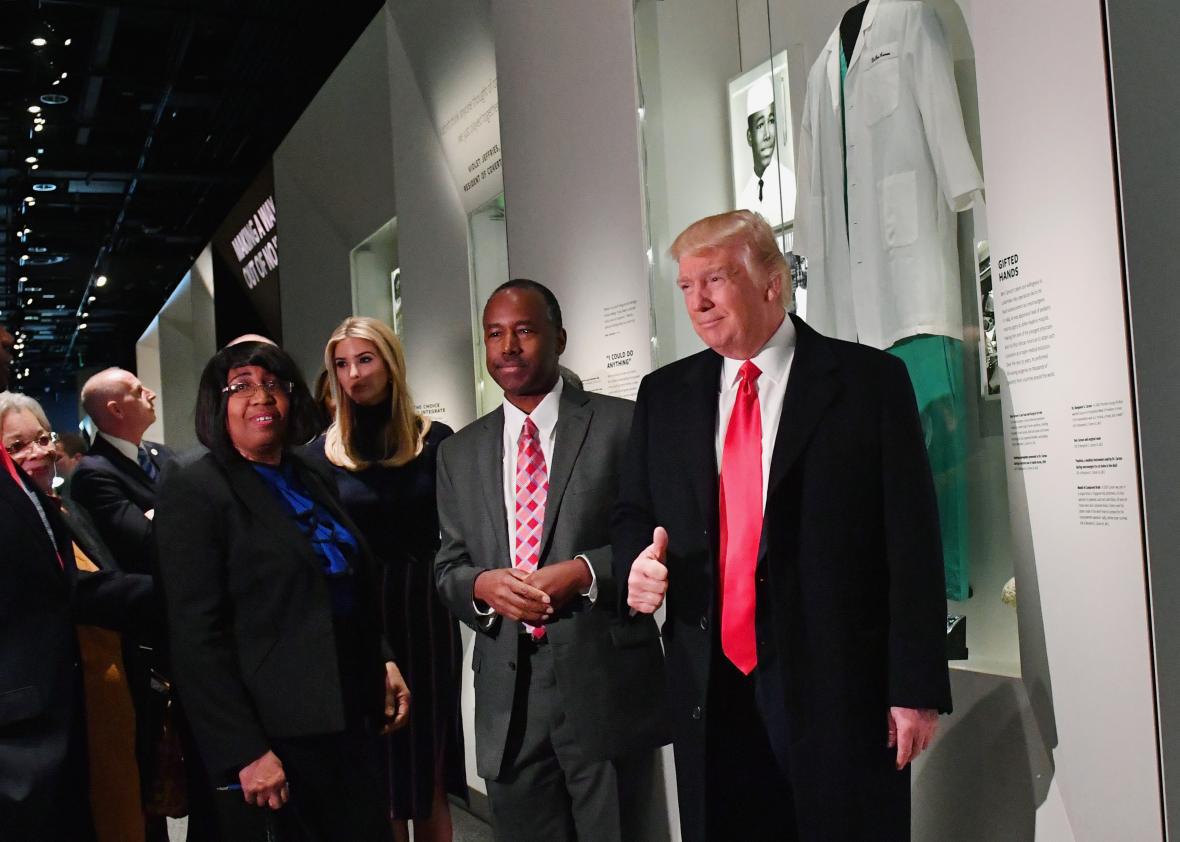

President Donald Trump spent Tuesday morning touring the National Museum of African American History and Culture, a makeup visit for the trip he was supposed to have made on Martin Luther King Jr. Day. One of Trump’s companions was Ben Carson, his pick for secretary of housing and urban development, whose career as a neurosurgeon is commemorated in one of the upstairs exhibits.

It would have been a good opportunity for the developer-president to update his notion of the “inner city” as a stand-in for black America, and perhaps even examine his own role in creating that stereotype.

Fittingly, there is nothing in the museum about Donald Trump’s own brush with fair housing law. In 1973, Trump was sued by the Department of Justice for refusing to rent or negotiate rentals with black tenants in the buildings his father had built in outer-borough New York City. The 27-year-old Trump vehemently denied the accusation. The standout detail from the case, which Trump settled in 1975 without admission of guilt but with a formal structure to help black tenants find apartments in Trump buildings, was that applications from blacks were marked with a C for colored. A review of some related documents released last week by the FBI reveals a blunter approach at some of the buildings in the Trump Management Co.: A black prospective tenant would be told there were no vacancies, despite a newspaper listing; a white prospective tenant would be shown an empty apartment immediately.

Tucked away on the third level of the underground history galleries at the NMAAHC is a room called “Cities and Suburbs” that to some extent tells the other side of this story: the diverse but largely segregated set of black communities that emerged during this era. Like the rest of the museum, its focus is on black agency—on places like Soul City, the utopian black community in North Carolina that the Washington Post called “perhaps the most vital experiment yet in this country’s halting struggle against the cancer of hectic urbanization.” The endeavor got a $14 million grant from President Nixon’s Department of Housing and Urban Development.

It was an era of outward migration from center cities for both blacks and whites, albeit at different speeds and to different places. Atlanta; Cleveland; Newark, New Jersey; and Los Angeles all elected their first black mayors between 1966 and 1974, a sign of burgeoning black political power and white flight. But the number of black residents in U.S. suburbs also would double between 1975 and 1985.

Discriminatory landlords helped ensure that old patterns of segregation would be perpetuated in neighborhoods where the building stock was nicer and newer. In one 1972 document from the just-released FBI files, for example, a white investigator for the New York Urban League posed as a renter at one of the Trump Management Organization’s Brooklyn buildings—middle-class enclaves in auto-centric parts of New York.

The rental agent told him that it was a “clean safe neighborhood, in part because it was controlled by the Mafia, but also because there are no blacks in the immediate area. He said the ‘people who made trouble’ … were kept within a limited part of the neighborhood which they seldom left, and assured that I would have little contact with them if I moved into the Beach Haven Apartment.”

“Do you mean blacks?” the investigator asked.

“You know what I mean,” the representative responded.

Did Trump’s mind flash back to those days, to his first mention in the New York Times, as he reviewed the museum’s catalog of black communities forged in response to redlining, restrictive covenants, and violence? We know he stopped by the exhibit on Carson’s former career; perhaps Carson could also learn something from Trump’s.