Back in early November (such a simple time!), I wrote a piece for Slate on political scientist Jonathan Rodden’s analysis of precinct-level voting patterns. Rodden, a professor at Stanford, showed that the familiar pattern of high-density Democratic areas and low-density Republican areas had been re-created, fractal-like, in the small towns and cities of the Rust Belt during Barack Obama’s presidential election in 2008.

These little-downtown voters, who helped Obama carry several swing states, were supposed to be irrelevant to the Democratic Party in 2016, as Chuck Schumer infamously said in July: “For every blue-collar Democrat we lose in western Pennsylvania, we will pick up two moderate Republicans in the suburbs in Philadelphia, and you can repeat that in Ohio and Illinois and Wisconsin.” After Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania flipped for Trump on Nov. 8, it was easy to think that small-town Democrats had abandoned the party wholesale.

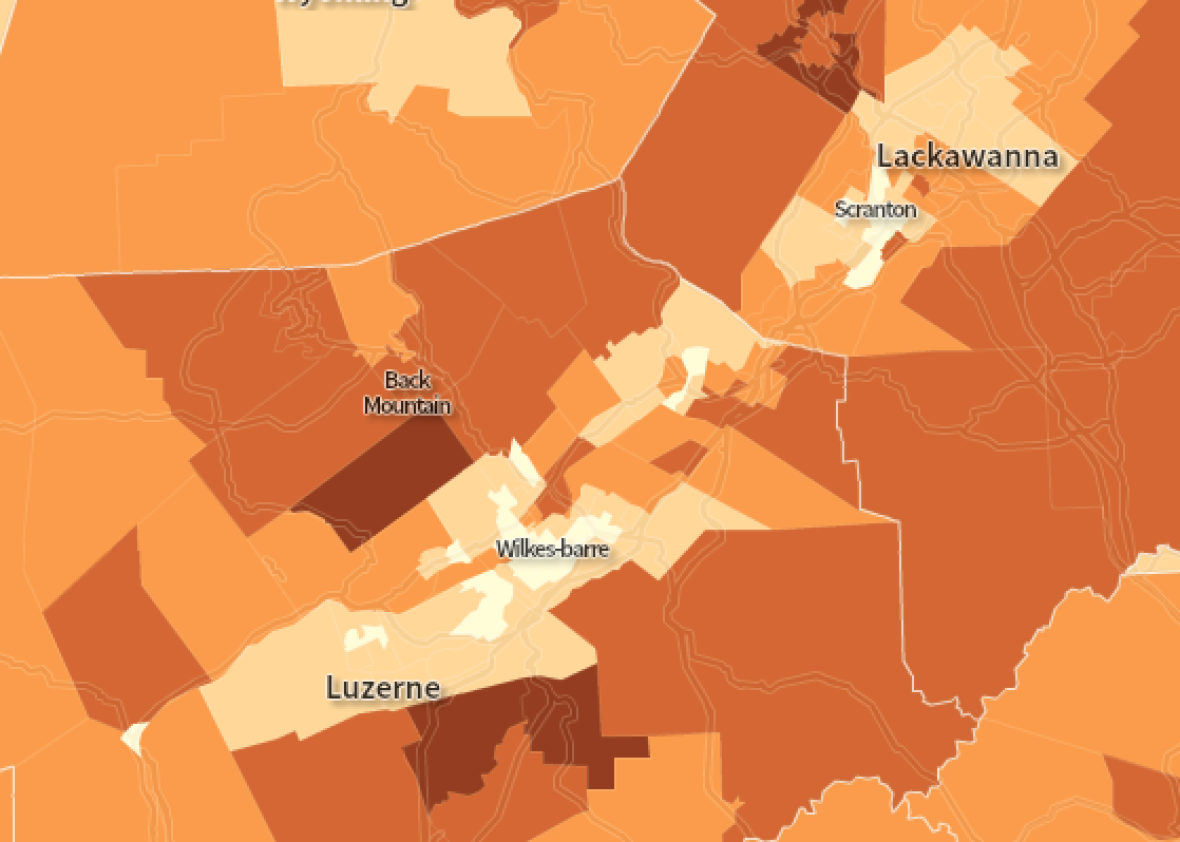

But it turns out Democrats didn’t lose those town cores in Pennsylvania and Ohio; in fact, as Rodden showed with new data this week in the Washington Post, the correlation between living downtown and voting Democrat was (relative to nearby rural areas) just as strong in this presidential election as in its predecessors. Red counties weren’t homogenous before, and they’re not homogenous now.

Rodden thinks this trend rebuts a common cultural trope about small-town America: “A popular claim is that Trump’s populist anti-trade rhetoric resonated most in postindustrial towns with severe job losses,” he writes in the Post. “If so, we might expect that these towns suddenly started to vote more like their neighboring Republican precincts, with the graphs flattening in 2016.”

In fact, his graphs show two things: First, Clinton did worse across the board in all these counties than Al Gore, John Kerry, and Obama (both times). Second, her returns mirrored almost exactly the existing correlation between population density and politics. People who lived closer to downtown were still more likely to vote Dem.

I’m not sure Rodden is right to characterize the downtowns of Ashtabula, Ohio, and Muncie, Indiana, (among other places) as more stung by industrial job loss than their outskirts. They were once. But John Updike’s America, where Harry Angstrom could take the bus home from his job as a linotype operator, is a long time gone. Manufacturing work has taken place outside of downtown for many decades. The top four small metro areas for job sprawl, according to a 2009 Brookings analysis, were all post-industrial Northeast cities: Poughkeepsie, New York; Scranton and Wilkes-Barre in Pennsylvania; Youngstown, Ohio; and Worcester, Massachusetts. In Scranton/Wilkes-Barre, for example, more than half of all jobs are more than 10 miles from the two cities’ downtowns. That’s not new. So when the plant closes, it shouldn’t burn downtown voters more than others.

Still, whatever voters’ grievances about deindustrialization, there are other correlations that would tip these old town centers—Scranton, Wilkes-Barre, Reading, and Johnstown, in Pennsylvania, for example—toward Democrats. For one thing, they are almost all poorer than their suburbs. For another, they all have concentrated minority populations. They also have more rental housing, and their residents ought to have a closer relationship to the public assets that Democrats have traditionally championed, like universities, libraries, parks, and transit.

For Democrats, the problem with these people isn’t that they didn’t vote Democratic; it’s that they didn’t vote at all. In some cases, turnout in downtown precincts was about half what it was a few miles away. Clinton still carried them.

This, then, is an optimistic message about left-wing politics in non-metropolitan America: Those deep-red swaths of countryside in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana are more politically diverse than they look. It just depends on your frame of reference.