Back in January, I published a post titled, “Could This Map Make Donald Trump President?” Here was the map in question.

David Autor, Gordon Hanson, David Dorn

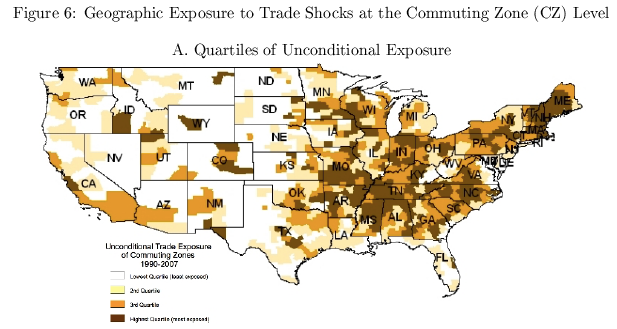

It was from a paper by economists David Autor, Gordon Hanson, and David Dorn, and it showed the extent to which industries in different parts of the country were exposed to competition from Chinese companies through 2007. The darker the region, the more vulnerable local manufacturers were to the onslaught of imports that came out of the People’s Republic, particularly after it joined the World Trade Organization. In a series of studies, the authors had shown that trade with China had cost the U.S. far more jobs than previously understood, perhaps as many as 2.4 million, concentrated in factory towns across the country. I figured that if Trump had a path to victory at all—and like most people I was pretty sure he didn’t—it might run through the map’s brown swatches in the Rust Belt, where his rhetoric on trade would play well.

We all know what happened next. And while we’re not going to be done arguing any time soon about how much of Trump’s victory was driven by economic misery versus pure racial backlash by working class whites, Autor, Hanson, and Dorn are now out with a short study suggesting that job losses to China really did play a role. They compare the share of votes won by George W. Bush in 2000 and Donald Trump in 2016 across 2,971 counties, and find that the GOP gained more ground between those two elections in places where local industry had faced a greater increase in competition from Chinese goods. They then set up a counterfactual simulation, and find that Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina would have gone blue this cycle had Chinese import penetration been half as large. (Think of that less as a cold, hard fact than as a gestural illustration about the size the effect they find.)

The point here isn’t that people in Michigan or Wisconsin cast their ballots for Trump specifically because of his trade stance. It’s that he outperformed his predecessor in places that were more likely to have been ravaged by the effects of globalization. Autor told the Washington Post that he believed that voters weren’t just reacting to “trade policy, per se,” but that disappearing jobs fed into a ”sense of nationalism, the sense that the American way of life is potentially threatened, and that a certain type of employment and a structure that went with that is going extinct.” You could also say that people simply reacted to the growing misery around them—another recent paper found that communities exposed to Chinese competition saw suicide and drug overdose rates rise, particularly among whites. And Trump captured their frustration.

I do have mixed feelings about some of the methodological choices in the study, which is still only a draft. (It’s technically an appendix to a previous paper that found voters became more politically polarized because of trade with China.) Instead of looking at the overall percentage of votes Trump and Bush won, for instance, the authors calculate their “two-party vote share,” which is the number of Republican votes divided by the sum total of Republican and Democratic votes. That means third-party ballots are excluded. And part of me wonders whether cutting Ralph Nader, Jill Stein, and Gary Johnson from the math makes sense, given the role they played in both the 2000 and 2016 cycles. Part of me would also like to see what happens when you compare the 2012 and 2016 maps, since the question on so many people’s minds right now is why Clinton couldn’t carry the same states as Obama. (In a brief email, Autor told me that analysis would be tricky, but he’d update me if his team ever got around to it. One can dream.)

Still, this is some of the first rigorous work that tries to examine the link between trade and Trump’s victory, which makes it useful. A previous paper, released during the campaign, found that Trump support wasn’t related at all with China’s effects on local industry. But that work was based on Gallup data, and polls didn’t exactly do a hot job calling the Midwest this cycle.

In general, I don’t like monocausal explanations of Trump’s win. Race obviously played a role. So did a sense of declining prospects. A lot of Americans were obviously angry about vanishing factory jobs, but in reality that has as much or more to do with automation as offshoring. But at the very least, this new study is a reminder not to discount the role of economics in fueling Trump’s support. Maybe if we hadn’t taken such a laissez faire approach to trade and let such large swaths of the country decay, voters would have been a little less susceptible to demagoguery.