Uber and Airbnb may seem like they’re everywhere these days. But they’ve grown fastest—in some cases, at more than twice their national rate, according to a new analysis—in just a handful of American cities.

In a report released Thursday, Ian Hathaway and Mark Muro of the Brookings Institution make the case that U.S. Census data on “nonemployer firms,” which tracks the activity of businesses that earn at least $1,000 but have no employees, can serve as a good proxy for the independent contractors that underwrite the business model of companies like Uber. (That Uber drivers are characterized as contractors has been the source of controversy and lawsuits, but more mundanely, has also made it difficult to measure the extent and distribution of the startup’s workforce.)

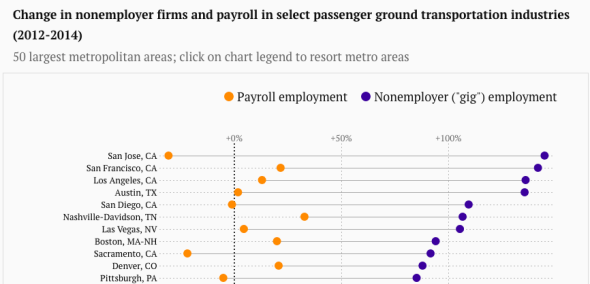

Muro and Hathaway split up payroll growth in ground transportation (read: taxis) and traveler accommodation (hotels) from “non-employer firm” growth in the same fields (i.e., Uber, Lyft, and Airbnb), and sort by metro area. What they find is very uneven growth between metropolitan areas, in a way that can’t be accounted for by the services’ own segmented expansions. In the four largest cities in California, nonemployer ground transportation jobs surged more than 100 percent between 2012 and 2014. In Chicago, an early Uber launch city, those jobs grew less than half as fast. In New York, the rate was half that, and less than half the national average.

Brookings Institution

Those city-by-city comparisons lose some value because of the timing: Two years ago was a long time in Uber-world. Service didn’t even launch in Miami; Austin, Texas; and Orlando, Florida, for example, until halfway through 2014.

Still, nonemployer firms spike at just the right time to make sense as a proxy for startup gigs. And there’s another interesting data point here: It doesn’t look like there’s much evidence that growth at Uber and Airbnb is coming at the expense of jobs in the taxi and hotel industry. In the fastest-growing cities in the country, payroll growth pokes above 5 and 6 percent. But payroll employment in ground transportation—“taxis and limousines” and “other transit and ground passenger transportation”—surged by double-digit percentages in many cities where ridesharing also seemed to be taking off. That’s kind of shocking, given the heat on taxi companies. It’s also possible that over the past two years, that growth has dried up.

The most important point here may be the strong relationship between independent contractors and cities. It’s easy for urbanites to greet Pew’s finding, from May, that only 15 percent of Americans have used a ride-hailing app, with skepticism.

But these new statistics reinforce the idea that this new economy of temporary work, whatever we want to call it, has a huge geographic bias. In the rides sector, more than 80 percent of four-year net growth in non employer firms took place in the 25 largest metros. They contain just 43 percent of the population.

You’d think that these companies offering rooms, rides, and odd jobs on call could use their virtual prowess to defy the geographic tendencies of regular employment. In fact, their growth has been highly varied not only between big cities and the rest of the country—which might be expected—but also between big cities themselves.