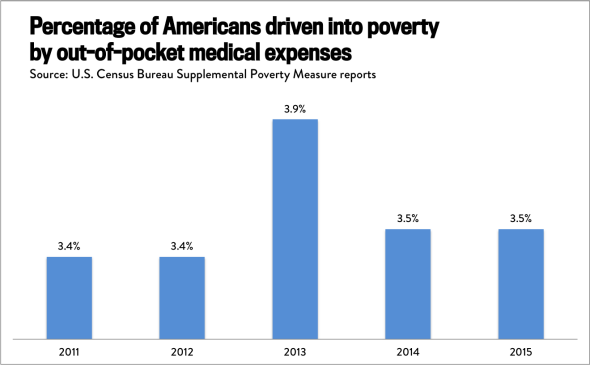

On Tuesday, the Census Bureau’s big annual report on U.S. income and poverty trends confirmed that the country’s uninsured rate continued to drop in 2015 thanks largely, no doubt, to the effects of Obamacare. However, the report contained a subtle down note about the health care landscape. Even though the percentage of Americans who lack insurance is declining, the percentage being driven into poverty by medical expenses has remained stubbornly stuck in place.

Based on an analysis of its so-called Supplemental Poverty Measure, the Census Bureau reports that 11.2 million individuals were pushed below the poverty line last year thanks to out-of-pocket medical spending, including insurance premiums, prescription drug costs, and doctor’s office co-pays. Overall, those expenses drove up the supplemental poverty rate by 3.5 percentage points, little changed from most recent years.

Jordan Weissmann

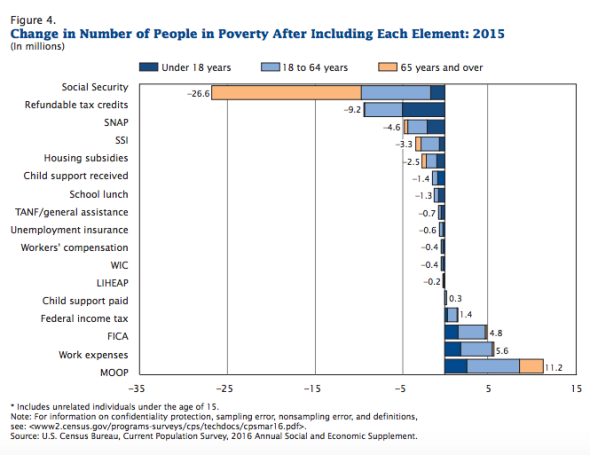

Economists widely consider the Supplemental Poverty Measure, or SPM, to be an improved, modern alternative to the official poverty line. There are a few reasons why. First, the official poverty figure we’re used to hearing about is pretty anachronistic—it was set at three times the cost of food in 1963, and has mostly just been updated for inflation since. It also only counts cash income, so in-kind government benefits like food stamps that play an essential role in the safety net aren’t counted. The SPM, in contrast, is based on the the average spending on essentials for contemporary lower-income families and is adjusted to reflect how housing costs differ across the country. Most crucially, it also counts a family’s total financial resources, totaling up income after taxes and government transfers, while subtracting work and medical expenses.

Currently, about 45.6 million Americans, or 14.32 percent, are in poverty as measured by the SPM (that’s slightly higher than the official rate). Again, the bureau notes that were it not for medical out-of-pocket expenses (MOOP, on the graph below), “11.2 million fewer people would have been classified as poor.” That means medical expenses are driving more people into poverty than refundable tax credits or food stamps are pulling out of it.

Census Bureau

It’s discouraging that these numbers haven’t noticeably improved in the wake of Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion, which was designed to extend health insurance to more of the poor and near-poor, and went into effect in 2014 (yes, as my graph shows, the percentage in poverty due to medical bills fell that year, but the spike in 2013 looks sort of aberrant). After all, research has shown that, as you might expect, families that enroll in the program tend to experience less financial hardship due to health care bills. If the expansion were to succeed at anything, you’d think it’d be reducing medical poverty. Of course, part of the problem is likely that many states have refused to expand eligibility, and those holdouts have higher overall uninsured rates among the borderline poor at risk of being knocked into statistical impoverishment by an unexpected doctor’s bill. If states like Texas and Florida ever embrace the expansion—I know, big if—we might one day see fewer Americans going broke because they got sick.