It’s been three years since Toronto, boosted by its late-’90s amalgamation with its suburbs, surpassed Chicago to become North America’s fourth-largest city.

Now it may get a public space befitting the title.

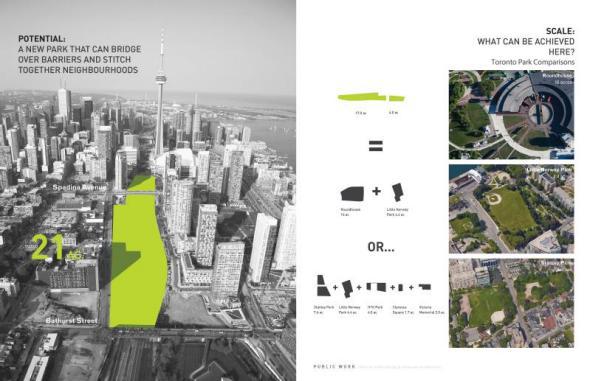

On Wednesday, Mayor John Tory announced a plan to build a 21-acre park on top of the rail yards in the city’s downtown core. That’s about twice the size of Los Angeles’ Grand Park and considerably larger than Boston’s Rose Kennedy Greenway. Under a full build-out of 27 acres, including an adjacent site, the Rail Deck Park could be as large as Chicago’s Millennium Park, which the city cites as a model.

Should the plan go through, it would be a rare and enormous victory for public space over private development, a contribution to the city that doesn’t require turning over parkland for condominiums, stadiums, or other private uses.

If Toronto can pull it off, that is.

Over the past two decades, Canada’s financial center has experienced a downtown residential boom that most American cities could only dream of. Once equal parts corporate and post-industrial, the area has added 50,000 residents in the past five years alone, and planners estimate its population will double by 2040 to 475,000. As in any business district, the crowds spike daily.

“Downtown is the Golden Goose,” Toronto Chief Planner Jennifer Keesmaat explained to me over the phone. “If you take the downtown core out of Toronto you have a city in decline.” It is also the part of the city with the least park space per person—a quality that a recent city survey found was second only to schools in importance to families raising kids in high-density areas. Toronto has reacted to the boom with a network of pocket parks and other green spaces but has had trouble acquiring sizable parcels for parkland in the high-priced core.

So Toronto will build a park that the mayor said would provide residents with “an experience that is unique to Toronto,” and which Keesmaat has called “our Central Park.” The planner said she hoped the park would emphasize Toronto’s wintry character, with snowshoeing or cross-country skiing trails meandering beneath the skyscrapers.

City of Toronto

If the mayor can shepherd the plan past the City Council and negotiate the purchase of the air rights in the corridor—by no means guaranteed—the Rail Deck Park will be the latest in a string of eye-catching projects built on decks atop highways (like Klyde Warren park in Dallas) or rail yards (like Hudson Yards in New York). In Toronto, it will represent a renewed focus on downtown after the contentious years of the Rob Ford administration, which perpetuated a culture war between urban and suburban Toronto.

It’s hard to build big parks in hot neighborhoods, and the more needed the park area is, the more expensive it gets to build. New York City saw this happen in Williamsburg, where planners promised a park in exchange for a rezoning to allow waterfront towers. The neighborhood’s transformation has since driven the asking price of a six-acre, burned-out document storage facility, a planned part of the park, up to $325 million. (The city offered $100 million.)

Here, Toronto has an advantage. Toronto has been collecting parkland money for years from a tax on new development, especially from the downtown area. But the city has trouble competing with private developers for land downtown. While the coveted Brooklyn parcel could legally become office space, Toronto’s rail yards are zoned as a transportation corridor. Planners hope the City Council will vote to designate the whole area as open space, thereby definitively ending any aspiration the rail companies might have to sell air rights to a private developer.

In a thoughtful analysis for Spacing, John Lorinc tells the cautionary tale of another Toronto park that wound up clumsily subsidized by real estate development. I asked Keesmaat if, given what New York has done with Hudson and Atlantic Yards (two rail yards mega-developments that are mostly buildings, not parkland), there isn’t pressure to turn the land over to private developers and rezone it for high-rise residential and office space.

She sees that possibility as a risk, rather than a prospect. “This is really the last opportunity to create a park of this scale,” she says. “Why would we take this precious continuous band and compromise it in any way?”

We’ll see if the tax-averse Toronto City Council agrees with her about that.