Ridership statistics from the past decade suggest that Americans have gotten off the bus.

Even in New York City, despite record population gains and new highs for subway ridership, bus ridership has fallen by 16 percent since 2002. Bus ridership in D.C., after a good decade, is down 6 percent this year on weekdays despite the troubles of the regional subway system.

Nationwide, bus trips have fallen from 5.86 billion in 2002 (a peak year) down to 5.11 billion last year, and dropped almost 3 percent between 2014 and 2015.

What’s to blame? Low gas prices, the recession, investments in rail, competition from Uber and bike-share? A new Bus Turnaround Campaign in New York, undertaken by research and advocacy groups, suggests that the fault lies largely with the bus service itself and that the city—and, implicitly, other American cities—has the power to restore the bus to the urban transportation toolkit.

A report published on Wednesday by the Transit Center, a nonprofit that studies and promotes transit, notes that New York City buses have an average speed of just 7.4 miles per hour, slower than their counterparts in San Francisco, Chicago, Boston, D.C., Philadelphia, and Los Angeles.

From a design perspective, New York’s bus network—like those of many U.S. cities—is a messy relic of the streetcar age, a document of obsolete travel patterns and forgotten contracts. (See how few buses travel between Brooklyn and Queens, for example.) Many routes have stops within a stone’s throw of the next one. Others go on for miles and miles, making it less likely that buses will be properly spaced and on time.

Buses here and in other cities have been slow to adopt new technology. One-touch payment systems, like those used in San Francisco and London, can cut boarding time by up to 40 percent. (New Yorkers sometimes wait several minutes to board at busy local bus stops.) Estimated arrival times, the Transit Center suggests, can easily be advertised at stops and improve the travel experience.

Finally, transportation engineers have developed a number of street design innovations that can make bus service faster and easier. These include dedicated bus lanes, sidewalks designed to facilitate boarding, and traffic signals coordinated for buses.

All these changes would make buses a faster and more reliable mode of transit. But what if people just don’t want to take the bus, regardless of the quality of the service? That’s probably not what’s happening. The decline in ridership seems to be a result not of competition with Uber or low gas prices—but with service cuts.

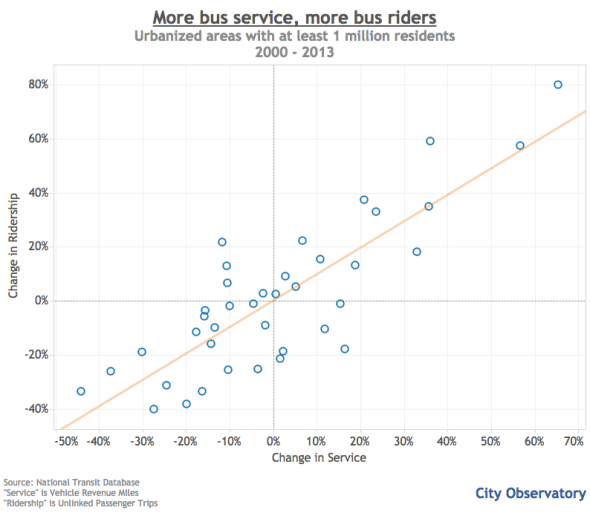

In 2015, Daniel Kay Hertz of City Observatory crunched the numbers and found “a very tight relationship between places that cut bus service between 2000 and 2013 and those that saw the largest drops in ridership.” It’s a phenomenon that holds even after controlling for other factors, research shows. Cuts prompt ridership declines, not the other way around.

What’s cool about New York’s Bus Turnaround Campaign is that it shows that good bus service isn’t solely dependent on running more buses—but on running them smarter. Better routes, well-spaced stops, information technology, and complementary urban design and traffic laws: These, as much as the actual buses, are the ingredients of a good transit system.