One big question hanging over the candidacy of Hillary Clinton is how she’ll use her presidency if she wins the White House in November (current probability: high) but finds her agenda stymied by Republicans in Congress (current probability: also high). This is an especially tricky issue when it comes to the economy, since big domestic initiatives typically need to make it through Capitol Hill.

Conveniently, Elizabeth Warren, who of course happens to be on Clinton’s vice presidential shortlist, just threw her weight behind one idea that could help fill in the blank: make antitrust law great again.

That was the message of a major speech the senator from Massachusetts delivered Wednesday at the New America. For better or worse, much of the news coverage it generated focused on Warren’s suggestion that tech giants Apple, Google, and Amazon have used their massive platforms to “snuff out” competitors. But her bigger theme was that Washington’s lax approach to antitrust has left all sorts of industries, from banking to beef production to cable to airlines, dominated by a small handful of businesses, and that in turn has hurt consumers, small businesses, and the middle class. “Anyone who loves markets knows that for markets to work, there has to be competition. But today, in America, competition is dying,” Warren warned, before calling on regulators to get more aggressive about stopping mergers that would further consolidate the corporate landscape. “Strong executive leadership could revive antitrust enforcement in this country and begin, once again, to fight back against dominant market power and overwhelming political power.”

This is a subject that’s been getting increasingly popular among progressive policy thinkers—the Center for American Progress and Roosevelt Institute have both put out reports dealing with antitrust and competition issues this year, as has the White House Council of Economic Advisers. There’s a growing sense that the wave of corporate consolidations that began, more or less, during the Reagan era may be at least partly behind many of the ills currently ailing our economy—the growth of inequality, the decline of startups, the shrinkage of corporate investment, and even rising health care costs (hospital mergers are probably making your appendix surgery more expensive). The idea is that massive corporations have been able to use their market power (and lobbying dollars) to subdue competition and make a killing without spending to innovate like they used to. That allows their workers to collect massive salaries compared with their friends at less rapacious employers (some recent research suggests that income equality is driven as much by differences between companies as by differences between individuals or professions). “Today’s markets are characterized by the persistence of high monopoly profits,” Nobel Prize–winning economist Joseph Stiglitz wrote in May. He continued:

The implications of this are profound. Many of the assumptions about market economies are based on acceptance of the competitive model, with marginal returns commensurate with social contributions. This view has led to hesitancy about official intervention: If markets are fundamentally efficient and fair, there is little that even the best of governments could do to improve matters. But if markets are based on exploitation, the rationale for laissez-faire disappears. Indeed, in that case, the battle against entrenched power is not only a battle for democracy; it is also a battle for efficiency and shared prosperity.

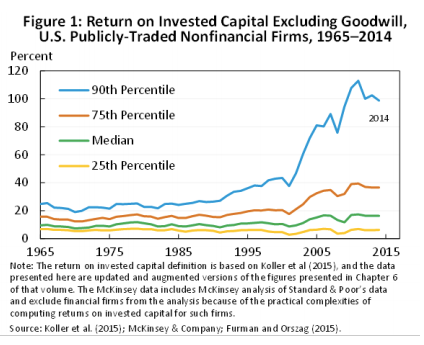

A lot of the evidence about monopoly power’s influence on the economy is, admittedly, circumstantial. But it’s still compelling. The Council of Economic Advisers notes, for instance, that the biggest tenth of public nonfinancial companies have seen their returns on capital investment skyrocket over the past decade and a half.

Now, maybe that’s because the tech industry offers amazing returns to scale and prizes are simply bigger for the world’s largest corporations because they can truly play on a global stage. Or, perhaps, the disappearance of competition from the market has allowed giant corporations to collect excessive profits—or “economic rents.” The truth could be a little of column A and a little of column B. But once you start considering the way mergers really do seem to be followed by things like price hikes or declines in research spending, the latter story starts to look at least plausible.

From a purely political perspective, meanwhile, getting back to good old-fashioned trust busting (or, you know, challenging a few more mergers) is appealing because it doesn’t require help from Congress. Yes, rewriting the laws to be more explicitly competition friendly would help. But the Reagan administration relaxed U.S. antitrust rules largely by rewriting the Justice Department’s enforcement guidelines to emphasize the conservative theories of Robert Bork, who basically said mergers should always be allowed if they encouraged economic efficiency and lower consumer prices. There have been rewrites since, but nothing truly fundamental. And while the Obama administration has been willing to stand in the way of some important megamergers—its thwarted the marriages of AT&T and T-Mobile and Comcast and Time Warner Cable, for instance—a Clinton administration could go further by rethinking the guidelines once more.

Americans are generally distrustful of big business, and there are mounting clues they have every right to be. So, who knows. If Elizabeth Warren doesn’t work out as VP, she might make an intriguing attorney general.