With Britain’s referendum on whether to depart the European Union fast approaching, Europe’s political leaders and major media organizations have been busy more or less begging U.K. voters not to bail. “Please don’t go!” the German magazine Der Spiegel urged on its cover earlier this month (German Chancellor Angela Merkel, true to form, was a little more restrained.) Sweden’s biggest financial newspaper resorted to an ABBA joke—“Take a Chance on EU”—while Hungary’s prime minister went and bought a full-page ad in the Daily Mail imploring the U.K. to stay. Then there’s European Council President Donald Tusk, who sounds like he’s one step from crooning some Al Green to the next Brit he spots on the street.

It’s understandable why Europe’s elite ain’t too proud to beg. The great fear among many is that a Brexit could encourage other nationalist movements and kick off a partial unraveling of the entire EU. Even if no other countries bid goodbye, the departure of Britain would still diminish and weaken the European project, the thinking goes.

But could that conventional wisdom be wrong? What if a Brexit is precisely what Europe needs in order to get over the seemingly intractable economic and political problems that have hobbled it these past several years? That’s the theory Andrew Lilico, a British economist at the consulting firm Europe Economics, puts forward in an interview Tuesday with Vox, which the site calls “the best argument for Britain to leave the European Union.” That’s slightly misleading. It’s more of an argument for why the EU should be happy to see Britain go.

Lilico argues that Great Britain is essentially holding back the rest of the EU from fulfilling its destiny as a fully integrated United States of Europe, which it needs to become in order to resolve the contradictions that have trapped it in an unending economic crisis. The eurozone, it is often noted, is a monetary union without a fiscal union. Members are required to live under the same interest-rate policies, which can make or break their economic growth. But there isn’t any system to transfer money from flourishing countries to struggling ones, the way the Washington transfers money from New York to Mississippi, for instance. As a result, you see massive disparities in unemployment and growth between countries like Germany and Spain (or, worst of all, Greece). The way to fix that, of course, is to become more like the United States: “they need eurozone-wide taxes, a eurozone treasury, an elected eurozone president, a eurozone parliament, and eurozone civil servants to manage expenditures,” Lilico writes.

The problem is that a handful of countries in the EU, including the U.K., don’t use the euro, and therefore won’t allow the necessary changes that would stabilize the currency union (after all, the British are already ticked off about the money they’re sending to Brussels).1 A Brexit, the argument goes, would fix that:

Once the UK is out, there will be enormous pressure on other countries to say when they will be joining. Countries that refuse to join will get rolled together with Norway (which isn’t in the single market but has a free trade arrangement with the EU). Then the eurozone can take full control of the EU’s institutions and be able to function properly to make it work as a currency union.

In short, the EU needs to reach a point where all of its members use the euro and therefore share the same common set of interests for the future. Brexit helps make that happen.

It’s not a totally crazy notion. The idea that the euro will continue to be a shambling disaster until Europe creates some sort of system in which rich Germans can lend a hand to poor Greeks is pretty much taken for granted among American observers, and a tighter fiscal union is most definitely a key part of the EU leadership’s long-term plan. And, who knows, maybe this would be easier to achieve if every country in the EU also was stuck with the euro.

But there are two problems. First, this isn’t really a reason for Great Britain to leave the EU—right now, it still gets the best part of membership (access to Europe’s free trade zone) without having to suffer through the worst aspect (being stuck in a bum currency bloc). And, unless you believe the pro-Brexit camp’s promises that the U.K. will be able to instantly negotiate wonderful free trade deals once it’s off on its own, seceding is still probably going to require some economic sacrifice for at least the medium term. In this case, what’s (maybe, theoretically) good for Paris and Berlin might not be so great for London.

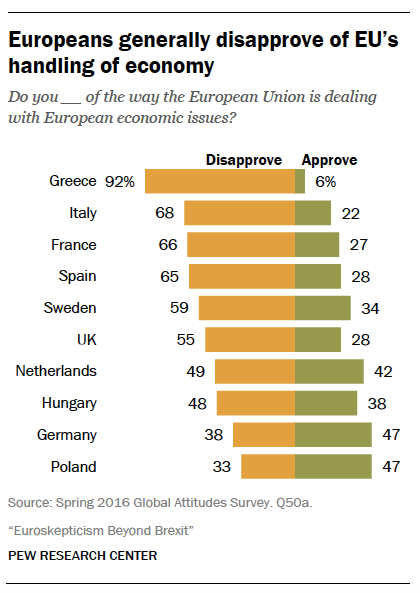

Second, it’s not really clear that freeing itself from Britain will really bring Europe much closer to a glorious federal future. As Pew has found, people also have a pretty unfavorable view of the EU in eurozone countries like France, Germany, and Spain—and the idea of national governments handing even more power to Brussels doesn’t go over particularly well anywhere. As of now, the notion of a U.S. of E. has next to no democratic legitimacy, and attempting to force it on voters seems like a recipe for more referendums like what’s happening in Britain.

Pew

Still, Lilico does make a fundamentally good point. So long as Britain is part of the EU, the fate of the eurozone will probably rest in part on the whims of a country that’s not part of it. Europe can’t live with Britain, even if it can’t live without ‘em.

1 He argues that the eurozone countries themselves could create their own rules and institutions separate from the EU’s existing infrastructure with some new treaties, but that’s unlikely to happen. Which sounds about right.