The Department of Housing and Urban Development proposed new rules this week that would allow tens of thousands of families to use federal housing assistance to rent more expensive apartments in nicer neighborhoods. It has the potential to change the makeup of the American city, facilitating mobility for poor residents and decreasing residential segregation.

In 31 of the nation’s largest cities, the rule would revise the concept of Fair Market Rent, or FMR, a regional value that determines the subsidy available to the 2.2 million households that receive federal housing (or Section 8) vouchers. Here’s how it works now: A voucher-holder finds an apartment, pays 30 percent of his or her income toward rent, and Washington pays the rest—up to the FMR.

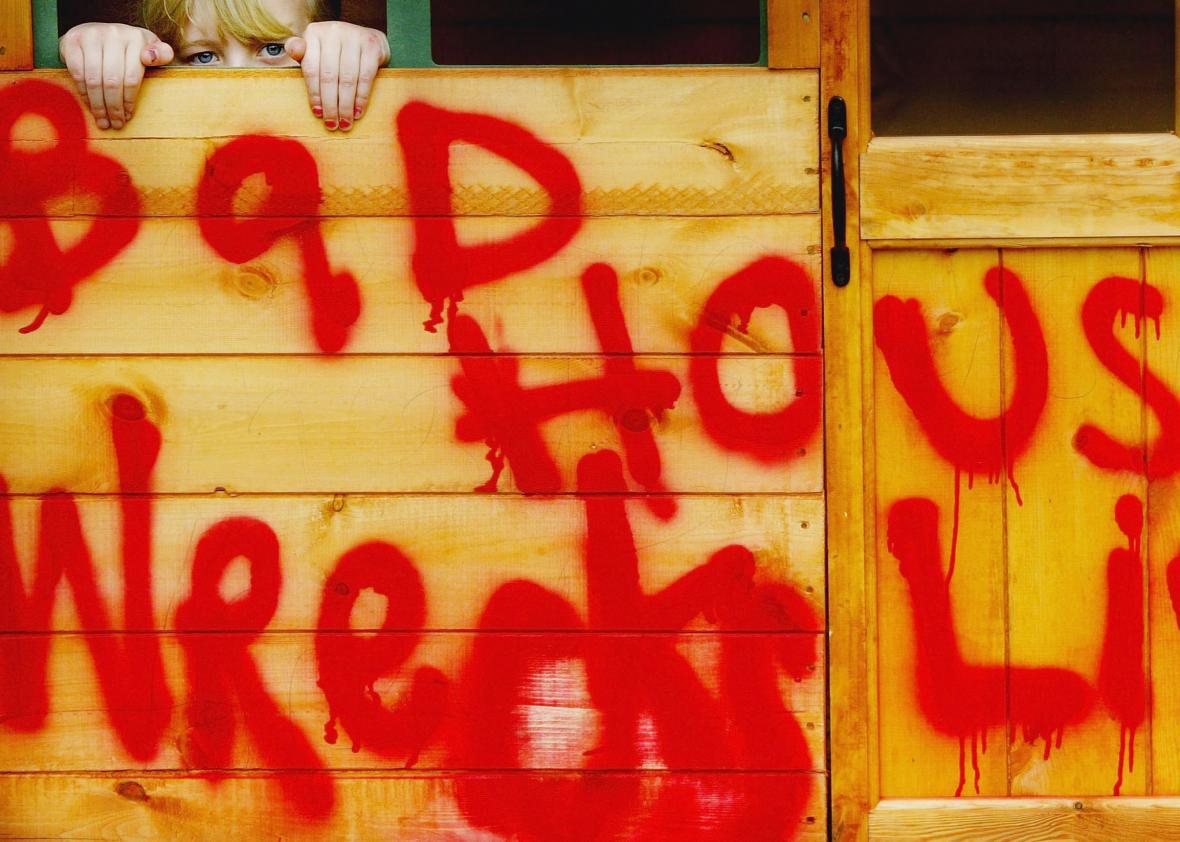

Having just one FMR (varied by apartment size) for a whole region means that expensive neighborhoods wind up with virtually no Section 8 tenants, while poor neighborhoods tend to be full of them. The Housing Choice Voucher Program, aka Section 8, was supposed to be an antidote to the concentrated misery of public housing projects, spreading low-income residents across whole cities; in reality, it hasn’t done much to distribute the geography of poverty. (Rampant discrimination against voucher-holders doesn’t help.)

Under the new rules, FMR will instead be set by ZIP code, so Section 8 will spend more money putting poor families in expensive neighborhoods. That reflects a growing consensus that getting poor families into good neighborhoods may be among the best anti-poverty tools we have.

“It is all part of a grand scheme to forcibly desegregate inner cities and integrate the outer suburbs,” the New York Post wrote last month about the changes. Sounds about right, except for the “forcibly” part. The plan’s success depends on poor families finding new apartments in new and unfamiliar neighborhoods.

A version of this policy has been underway in a handful of American cities, including Chicago, which has enabled hundreds of Section 8 households to move into wealthy neighborhoods—even a handful on Lake Shore Drive. Those account for less than 2 percent of the Chicago Housing Authority’s voucher recipients. But the idea of subsidizing the poor’s move into wealthy neighborhoods using “supervouchers,” as they’re known in Chicago, has unsurprisingly drawn “Welfare Queen” comments and some unscrupulous “watchdog” journalism.

Obviously, localized rent standards will mean the feds are paying more on behalf of some poor households. But the payoff should be well worth it: According to a 2015 Harvard study of HUD’s Moving to Opportunity program, young children whose families used vouchers to move to low-poverty areas were making 31 percent more, by their mid-20s, than their peers whose families had stayed behind.

And there’s a second component of the new HUD rule, too. In 2000, HUD raised its standards for Fair Market Rent from the 40th percentile of metropolitan rents to the 50th. It was hoped this would open up new neighborhoods to voucher recipients. Instead, HUD reports, most of the money went to landlords in the same neighborhoods, with the change “artificially inflating rents in some higher-poverty neighborhoods” where Section 8 tenants were concentrated.

This has low-income tenant advocates worried, especially since the old-style regional calculations tended to bump up FMR in the inner city by including wealthy suburbs (where Section 8 is a dirty word). The Wall Street Journal reports Friday that New York City “found that roughly half of the current Section 8 voucher holders in New York, or some 60,000 households, would see their subsidy levels go down, meaning they will either be forced to pay more rent or move.”

If HUD is right, there’s a third possibility: Rents in those neighborhoods, which had been jacked up by all that free federal subsidy, would fall.

Housing authorities in Dallas switched from a regional FMR to localized rent caps in 2011, and according to a 2014 Harvard-NYU study, which influenced HUD’s decision on the rule change, the results were excellent. “Because price increases in expensive ZIP codes were offset by larger decreases in low-cost ZIP codes, absent any behavioral response, this policy would have been cost-saving for the government,” the authors wrote. “Incorporating tenants’ improved neighborhood choices, the Dallas intervention had zero net cost to the government.”

In short, poor families got to live in safer neighborhoods with better schools. And it didn’t cost a cent.