Lee Gates, the cable-news host played by George Clooney in Jodie Foster’s fine but forgettable movie Money Monster, is plainly a fictionalized version of Jim Cramer, even though both the star and director have denied the parallel. He hosts a show called Money Monster on a business news network; Cramer’s nightly CNBC show is Mad Money. Like Cramer’s show, Money Monster is replete with sound effects, flashing lights, and catchphrases.

But more significantly, Mad Money and Money Monster recommend specific stock purchases to their less-than-sophisticated audiences. This is what sets the plot of the film into motion. Gates, you see, told his viewers to purchase shares in a company called Ibis, a high flyer in the world of high-frequency trading. But the share price of Ibis tumbled. As a result, Kyle Budwell, a 24-year-old package deliverer who lost his life savings following Gates’ advice, bursts into the studio and takes the celebrity stock-picker hostage.

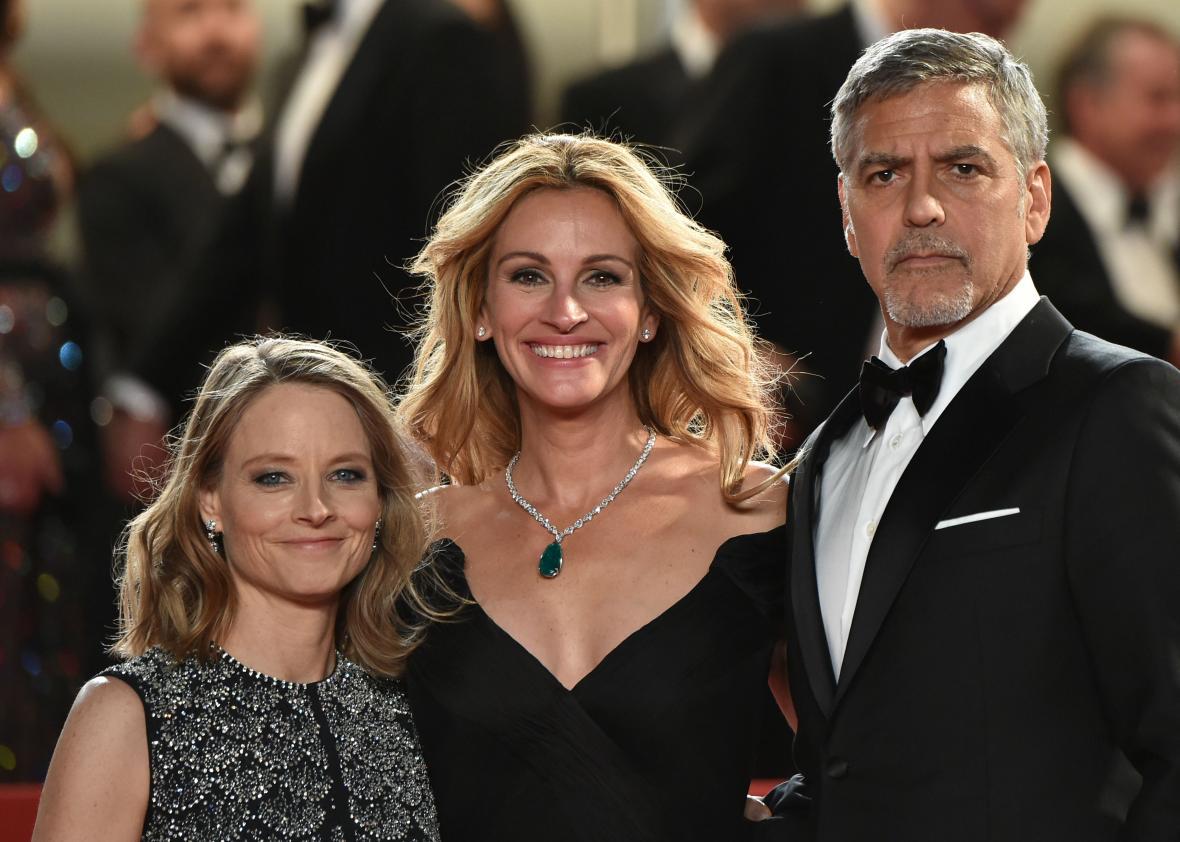

Before opening this past weekend, box-office projections for Money Monster weren’t exactly optimistic. “Ten years ago, Money Monster would probably have had moviegoers lining up,” opined Deadline Hollywood last week, nodding to the fading star wattage of Clooney and co-star Julia Roberts and its competition from Captain America: Civil War. But as it turns out, a lot of people did want to see this suspenseful, slightly dated-feeling drama. Money Monster emerged with a respectable $15 million opening weekend gross.

Money Monster’s premise wouldn’t appear to sit well in 2016. Who cares about cable business news? CNBC’s viewership is so down that network executives are claiming captive audiences in airports should count as viewers.

Still, it makes sense that the film is resonating: It offers gauzy wish fulfillment for anyone with the ambient feeling that someone, somewhere in this still-lagging economy, has done them wrong and got away with—especially anyone specifically still seeking a villain to punish for the financial crisis. Unfortunately, while Money Monster draws plenty of allegorical power from the 2008 crash, it doesn’t seem very serious about reckoning with it.

In the view of Money Monster, the issue isn’t that Gates is offering stock picks in what even the movie calls a “rigged” system—that he’s prodding people to gamble their savings in the name of entertainment. It’s that he was misled into making the wrong recommendation. So with a hostage-taker in the studio and cameras rolling, Gates and his producer Patty Fenn (Roberts) gamely set out to discover how Ibis went from sure thing to money loser. No surprise: In the end, a miscreant is called to account. Justice is sort of done.

Needless to say, it would be nice to believe that something similar went wrong in 2008—that isolated and individual mischief, not systemic failures and upper-upper-strata malfeasance, caused the economic crash—and that the bad guys did indeed receive their comeuppance. Alas. No top Wall Street figure was ever convicted of any crime. Even the settlements the United States government has made with financial services firms for various misbehaviors haven’t always been as significant as advertised. As David Dayen wrote last month in the New Republic about Goldman Sachs’ much-ballyhooed $5 billion settlement with the feds over the improper labeling of risky mortgages before the crash, “Even if you think Goldman is paying some kind of penalty, at best it’s a cut of the profits.”

A more ambitious film than Money Monster—or maybe one less concerned about being liked—might have taken a different route. It’s worth noting that the media cognoscenti never held Cramer’s Mad Money in high regard, even before Jon Stewart famously took off after it and CNBC it in 2009. And little wonder. You don’t have to think too hard to realize that anyone who actually has the stock market figured out probably has better things to do than tell people with a few spare bucks about his insights. As Henry Blodgett wrote in Slate back in 2007, about a year after the show first went on the air, “The more I thought about Cramer, the more I realized that pointing out that he gives terrible investment advice would be like pointing out that the sun rises. Worse, I would be dismissed as a wet blanket who didn’t get that the point of Mad Money was just to have a bit of ironic fun.”

Stock pickers forever claim to be on the side of the individual investor. The movie appears to take this belief at face value. Describing the struggle between Budwell and Gates, Foster told Yahoo the movie was about “two men who feel like failures”—a comparison that only stands up if you believe calling a stock wrong is as awful as losing all your money on it.

What Stewart made clear to anyone who wasn’t paying attention was that Cramer—not to mention his network—was playing for patsies the portion of his audience that actually bought his shtick. No doubt Mad Money never meant to lead anyone astray—that was merely an inevitable impact. If, say, Cramer had begged his audience to stay away from individual stocks because they would likely do better with index funds, he wouldn’t have a show and CNBC wouldn’t have a business model.

Money Monster might have made for a pointed media satire had it gone to the heart of that problem—had it explored how large economic headwinds can subsume the everyman with the help of supposed saviors who in reality are enabling systemic dysfunction. Instead, it takes the fuzzy, feel-good, and morally righteous position. In the end it offers Gates a bit of redemption, which might explain Money Monster’s appeal: It nails a villain and ties a bow on things—atrocity over. Meanwhile, the rest of us are still waiting for someone to take the fall—someone other than us, I mean.