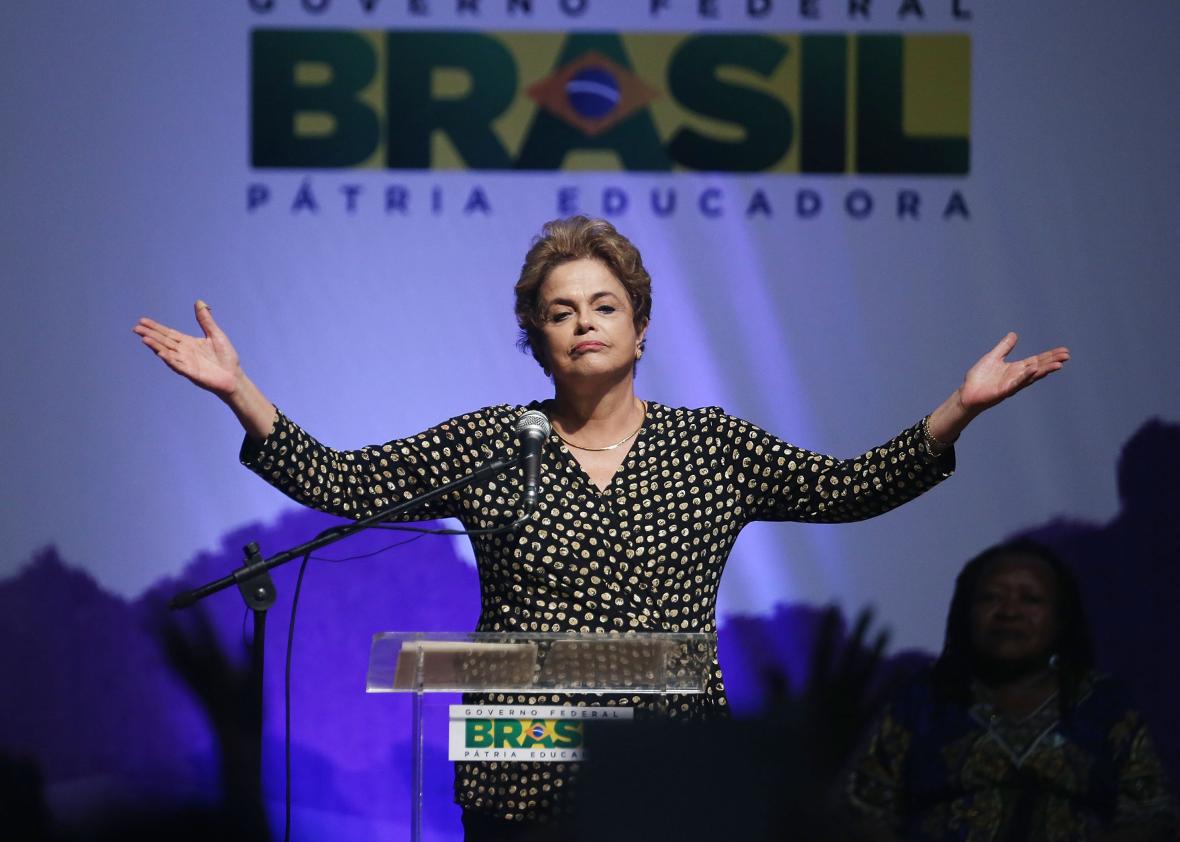

Miami didn’t get a vote in the Brazilian Senate’s decision early Thursday morning to impeach President Dilma Rouseff, who was suspended from office and will face trial on accusations of financial mismanagement. But the agonies of the vote, and the corruption scandal at large, have been felt and followed in the so-called Capital of Latin America, which functions as a surprising barometer of the continent’s troubles.

Nobody spends more time in Miami than Brazilians. Though a trip to South Beach costs them twice as much as it did two years ago due to the unfavorable exchange rate, nearly 750,000 Brazilians flew into Greater Miami in 2015, up 2 percent from a year earlier. Now, empty hotel rooms in the city suggest that traffic has slowed during a political upheaval that has drawn comparisons to a coup d’état. Bloomberg reported this week that Greater Miami’s “revpar,” or revenue per available room, has fallen for four straight months, and that Marriott now considers Miami one of its weakest U.S. markets.

You’d think the Brazilian turmoil would actually be good news for Miami condo developers. Ninety percent of demand for new downtown condos there comes from foreign buyers, according to the Miami Downtown Development Authority. The buyer list for the 12 months ending in June 2015, according to a Florida Realtors survey, reads like a ranking of Latin American crises, with Venezuelans and Argentinians leading the charge, and Brazilians close behind.

That correlates with research out of Oxford University showing that, in London, “increases in political and economic uncertainty in specific foreign countries strongly predict price rises in their linked London areas.” When countries suffer, the theory goes, well-off nationals park their money in apartments in so-called safe havens like New York or Vancouver, British Columbia.

But as South America’s largest country dislodges its leader, Miami condos aren’t budging. In Miami Beach and Miami, sales are down 20 percent over the past year, to their lowest volume in three years.

“It’s a harder decision to make,” explains Jonathan Miller, a New York–based real estate consultant who watches the Miami market. “On the one hand you want to move to safety, capital flight. On the other, maybe you don’t feel as good about your position as you did two years ago because of the political and economic challenges.” A stronger dollar has also made buyers more cautious, he suggests. And the Miami condo market may be entering a downturn in any case, further warding off buyers.

Brazilians could also be taking their savings to cheaper markets. Art Falcone, the developer of the Encore Club in Orlando, Florida, says Brazilians are buying more than a third of the luxury resort’s vacation rentals. “We’ve seen an uptick in sales over the past 60 days as the impeachment process has played out,” Falcone told me.

The scale of international connection makes Miami unique among U.S. cities. But unlike in London, where development can’t keep up with foreign buyers, Miami developers seem to have leapt out ahead of demand. Last time this happened, in 2008, the result was a glut of cheap, downtown rentals. Hoping to get a cheap Airbnb in South Beach? Development fueled by foreign crisis is your friend.

What about Brazilians who purchased their pied-à-terres years ago?

Many weren’t looking at Miami as a place to make money, just to keep it. But Brazilians who bought in neighborhoods like Brickell or Edgewater several years ago will have made a big profit on the exchange rate alone. Brazilian politics may be messy, but the value of the real estate seems to be edging higher as the value of a Miami condo edges lower.

“If they know what they’re doing,” says Alan Lips, an accountant* at Gerson Preston who advises Brazilians on international investments, “it might be time for them to liquidate their U.S. assets and buy something in Brazil.”

Correction, May 12, 2016: This post originally misidentified Alan Lips as a lawyer. He’s an accountant.