Intrigued by what they perceived as the homogeneity of Chinese restaurant names, a pair of reporters for the Washington Post’s Wonkblog decided to analyze the names of nearly every Chinese eating establishment in the United States.

You will believe what they found.

Armed with geolocated Yelp data on more than 40,000 Chinese restaurants across the country, the Post’s Roberto A. Ferdman and Christopher Ingraham set out to test their scientific hypothesis that their names all sort of sound the same. Or, in the authors’ words, “we wanted to quantify exactly what the vernacular of American Chinese restaurant names sounds like.” One might think that is not the sort of thing one can quantify. But: data! And so: onward.

After sifting through the spreadsheets, our intrepid reporters report, “some interesting patterns became clear.” To wit:

The single most frequent word appearing in Yelp’s list of Chinese restaurants is, perhaps unsurprisingly, “Restaurant.” “China” and “Chinese” together appear in the names of roughly 15,000 restaurants in the database, or over one third of all restaurants.

Will wonders never cease?

“Express” is the next-most popular word, showing up in the names of over 3,000 restaurants. But as with “Panda” (2,495 restaurants), the numbers for “Express” are inflated by the Panda Express restaurant chain, which has over 1,500 locations.

No, they will not. Wonders never will cease.

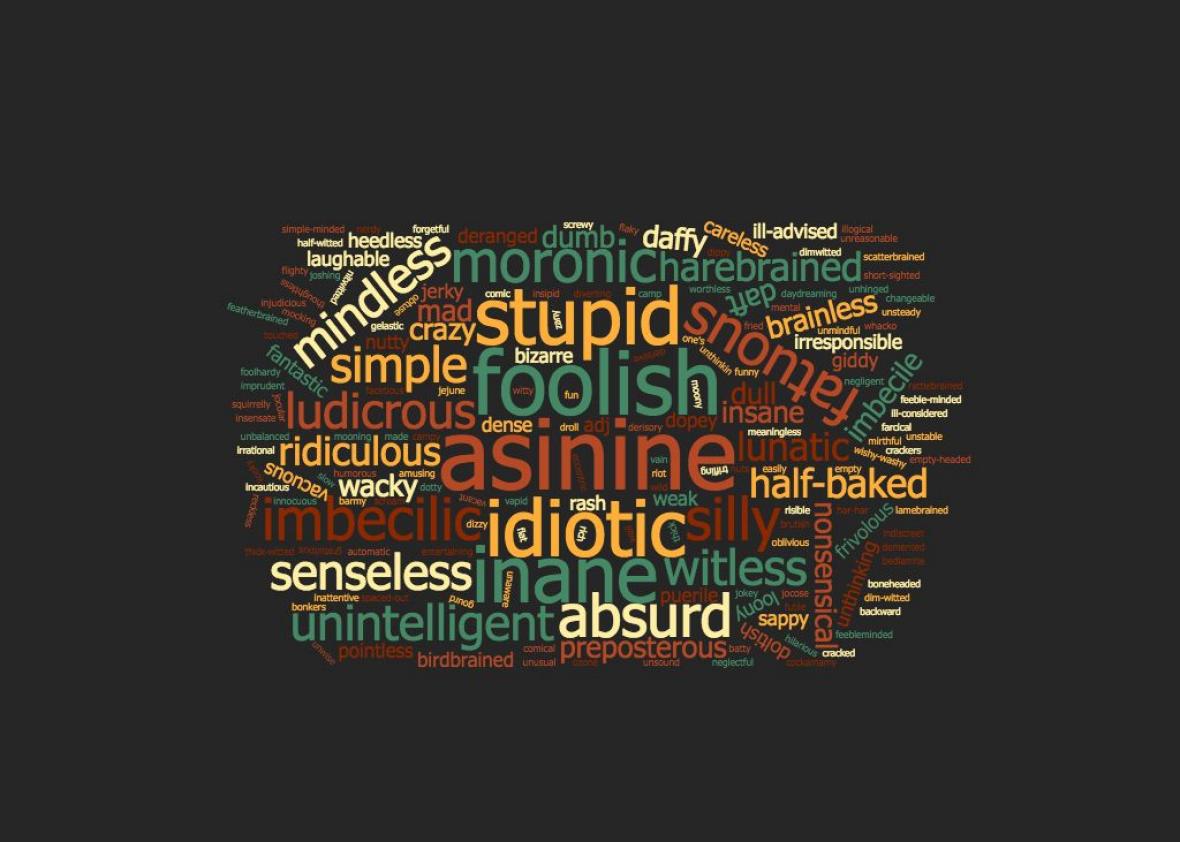

The story would have been delightful enough had Ferdman and Ingraham confined their analysis to prose. That, however, would have violated the first rule of data journalism, which is that you don’t just talk about the data. You must also visualize it. And so, we readers are treated as a bonus to two of my all-time favorite forms of data visualization: the word cloud and the heat map.

wordclouds.com

Both turn out to be shining examples of their respective genres. The word cloud is dominated by the words China, Restaurant, and Chinese, surrounded by a bunch of other words that one might commonly associate with Chinese restaurants. The heat map of Chinese restaurants in the United States, meanwhile, looks an awful lot like … well, I’ll let Ferdman and Ingraham tell you themselves. “Yes, this is essentially a population map,” they acknowledge. “Where there are people, there are Chinese restaurants.” (A second heat map, in which they control for population density, is only slightly more instructive, showing hot spots in New York, the Bay Area, Hawaii, and … the Nevada desert?)

Let’s pause here to give these journalists credit for coming right out and saying what anyone with half a brain who looks at a heat map is thinking. Throughout the piece, they forthrightly acknowledge that the findings of their great Chinese restaurant investigation are, essentially, not that interesting. And now they’re admitting that their data visualization doesn’t really convey a whole lot, either. This is a level of honesty rare enough in data journalism that it almost reads as a send-up of the genre, like #overlyhonestmethods or lolmythesis.

I don’t actually think it was intended in quite that spirit, because Ferdman and Ingraham go out of their way a bit to highlight the few tidbits they uncovered that might not have been utterly obvious in advance. For instance, they find more than 1,500 restaurants with the word “new” in their name, but only 31 with the word “old.” (Not that you’d ever gather this from the word cloud.)

Wait, was that only one tidbit?

Another, admittedly charitable, way to interpret this piece would be to view it in the context of the noble battle against the “file drawer problem,” which stems from the propensity of scientists to publish only those studies that turn up positive results. Less generously, one might imagine that the authors figured that after wasting so much time analyzing the names of Chinese restaurants, it would be a shame not to at least publish something.

“Taken together,” the authors sum up, “these maps do show the surprising ubiquity of Chinese restaurants all across the country.” Unless, of course, you’re in one of those places where they aren’t ubiquitous. But otherwise, they conclude, “you’re never really that far from Chinese cuisine—or from the very specific words that denote that cuisine in the American imagination.”

Like Chinese. And restaurant.