Because they are Democrats running for president in 2016, Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton have promised to raise taxes on the wealthy in order to pay for a generous new set of social spending programs. Sanders, of course, would treat America’s rich like a box of Celestial Seasonings bags, soaking them for all they’re worth. Clinton, being Clinton, is more incremental. But in Tuesday’s Wall Street Journal, Scott Winship of the conservative Manhattan Institute argues that both are basically selling the electorate a bill of goods.

“Proposals to soak the rich by raising their tax rates are unlikely to yield the revenue windfall that Mr. Sanders or Mrs. Clinton are dangling before voters,” he writes. “Leveling with the American people means either scaling back their agendas or admitting that they will have to raise the money from tax hikes on middle-class voters.”

This is a subtly bold statement. Forget, for a moment, Bernie’s plan to turn us into the United States of Denmark. Clinton has only proposed $1 trillion in new spending over 10 years, accompanied by about $1 trillion in new taxes to pay for it—a relatively modest sum in an $18 trillion annual economy. If Winship is right, then the left should pretty much pack it up and forget about funding any substantial new government spending with taxes on the very rich.

Winship’s position is also at odds with the economics literature of the past few years. Most everybody agrees that, in theory, there comes a point where raising taxes will actually cause the government’s revenue to drop, either because people will work fewer hours or will try to hide their money from the IRS. The Laffer curve, in other words, is real. But the U.S. doesn’t appear to be anywhere close to falling off the wrong side of it. Researchers Dirk Krueger and Fabian Kindermann, for instance, have suggested that the government could maximize its revenue if it slapped a 98 percent top marginal rate on the highest 1 percent of earners (right now, we’re at a measly 39.6 percent). Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Stefanie Stantcheva argue the golden number is probably between 57 and 83 percent. Sanders, by comparison, envisions a top income tax rate of a mere 54.2 percent. Clinton? Just 46.1 percent. The nonpartisan Tax Policy Center, which uses pretty mainstream assumptions about how workers and investors change their behavior when taxes rise, thinks both will raise plenty of money.

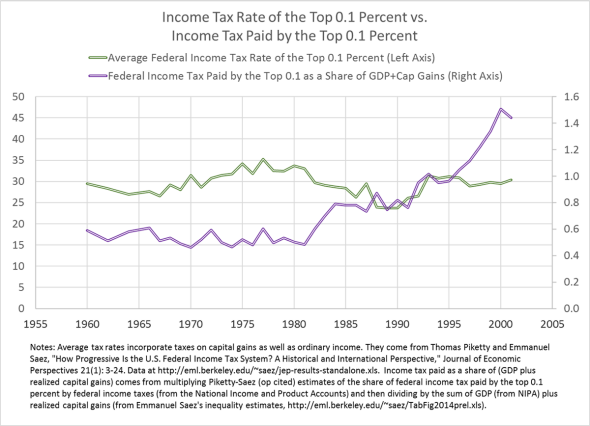

So what’s Winship’s argument? It mostly boils down to this graph, which shows that, even though the government raised rates on the top 0.1 percent during the 1960s and ’70s, their tax bill stayed basically flat or declined as a percentage of the economy, depending on the year you pick as a starting point. Meanwhile, as rates dropped in the ’80s, revenues from the rich shot back up. “This makes intuitive sense,” Winship writes. “Of all Americans, it is the wealthy who are more likely to take advantage of legal ways to reduce their payments when rates rise. Plus, their work and investment decisions are more sensitive to the after-tax payoff.” In other words, the government can’t fill its coffers by taxing the rich, because their accountants will just figure out a way around it.

Scott Winship

That’s reading a lot into two lines on a chart. After all, you could just as easily look at this picture and conclude that what the ultrarich pay in taxes simply has a lot to do with the health of the stock market. The average incomes of the top 0.1 percent fell during during the bear markets of the late 1960s and ’70s, before shooting up again as Wall Street roared back to life in the ’80s. Their tax bills followed a similar course. Maybe the superwealthy would have paid more to the IRS during the Nixon years if their portfolios hadn’t been getting murdered. Maybe they would have paid even less had their tax rates been lower. Winship can’t say.1 That’s why it’s a far leap from his brief history lesson about one particular era to the idea that the laws of physics have made it impossible to squeeze significantly more revenue out of the wealthy. At best, he can say that rates aren’t the only thing that determine the government’s tax haul, but everybody already agrees on that.

So until proven otherwise, soaking the rich still seems like a perfectly fine course of action. Carry on.

1It’s possible he could argue that rising capital gains rates dissuaded people from selling their investments and booking profits that would have been taxed, but even that’s a controversial subject.