The near-simultaneous rise of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders has often been described as a working-class revolt against globalization and free trade—a bipartisan protest by blue-collar voters who are angry after watching factory after factory close thanks to foreign competition. But some analysis of the recent Michigan primary is complicating that picture, especially when it comes to Sanders.

There are lots of good reasons to assume that Trump and Sanders are winning hearts and minds by lambasting trade deals. First, it’s been a big part of both their campaigns. Trump, especially, talks about trade constantly. In Trumpland, we’re losing to China. We’re losing to Mexico. We’re even still losing to Japan. “In fact, to judge by how much time he spent talking about it, trade may be his single biggest concern—not white supremacy,” the liberal writer Thomas Frank concluded after watching hours of Trump’s speeches. (Side note: I guess that’s mildly comforting?) The Republican front-runner has been especially popular among voters without college degrees, who’ve suffered most from the decline of American manufacturing. And the working-class whites who support him tend to say the economy is their top concern.

As for Sanders, well, he’s trying to woo the white working class, as well, and the man has never met a free-trade deal he likes.

Social science also gives us lots of reasons to think Trump and Sanders could be riding an anti-trade groundswell. Researchers have found that, as you might expect, Americans who live in parts of the country where industry has been hit hardest by foreign imports tend to vote against incumbent presidents. After two decades of free-trade consensus from both parties, Sanders, who dares describe himself as a democratic socialist, and Trump, who is Donald Trump, are campaigning as the ultimate anti-incumbents. The Michigan exit polls seem to bear this out, as Trump and Sanders both triumphed with voters who said that trade took away American jobs.

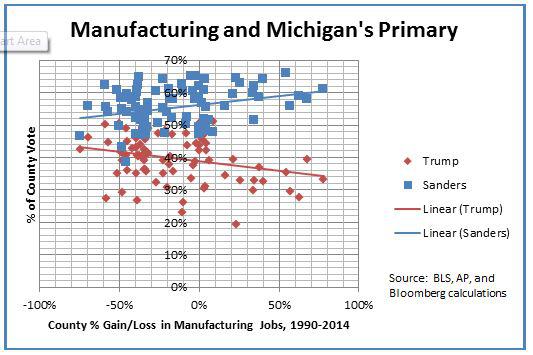

Brandon Greeley/Bloomberg

But then look at this graph from Bloomberg’s Brendan Greeley. It shows that, as you’d expect, Trump generally won a bigger share of votes in Michigan counties where manufacturing jobs declined the most between 1990 and 2014. But for Sanders, the opposite was true; he won a greater share of the vote in places were manufacturing declines were smaller.

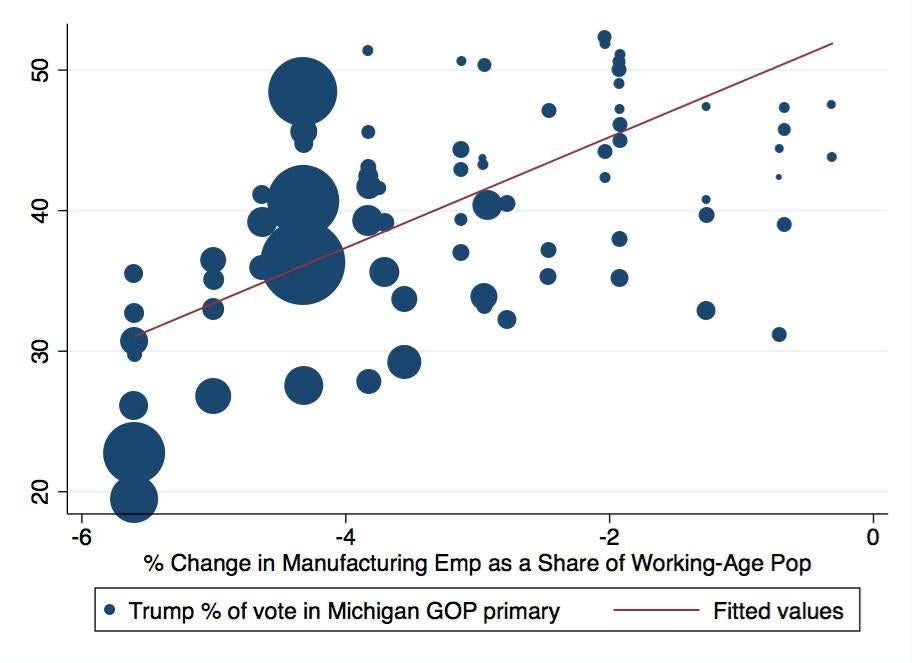

Evan Soltas

Using a slightly different approach, economics blogger Evan Soltas comes to the conclusion that neither Trump nor Sanders outperformed in areas especially hurt by trade. He compares the vote share won by each candidate to the local decline of manufacturing jobs as a percentage of the entire working-age population. For Sanders, he finds no statistically significant relationship: He wins about half the vote everywhere. Trump, surprisingly, tended to win more votes in areas where manufacturing employment declined least. In other words, he did best in counties where manufacturing should have mattered less.

Based on these graphs, the idea that Sanders won Michigan based on his trade stance looks fairly flimsy (notably, the exit polls said he only got 56 percent of the vote from those who said trade killed jobs). Regarding Trump, the evidence is contradictory, but I’m inclined to side with Soltas’ analysis. By looking at manufacturing declines as a percentage of population, he’s probably using a better proxy for trade’s impact on the local economy.

I don’t want to overstate the importance of these two charts. They’re just simple correlations based on the primaries in one state. But again, I do think they at least call into question the degree to which these candidates are actually winning among globalization’s losers.

Read more Slate coverage of the 2016 campaign.