Liberal policy wonks have generally been, shall we say, a bit cold on Bernie Sanders, especially when it comes to his plan for creating a single-payer health care system, which they’ve criticized as undercooked and unrealistic. But hostilities escalated this week when four former chief White House economic advisers issued a harsh open letter accusing the Vermont senator of embracing “extreme claims” about how his policy ideas would boost American growth and of sullying Democrats’ entire reputation for caring about “responsible arithmetic.” The spreadsheet-wielding wing of the party has basically declared that the Sanders campaign is deluded about economics.

Is it? Either deluded, or sloppy. Which is an especially bad sign if you care about policymaking.

Why are economists freaking out about Sanders’ math?

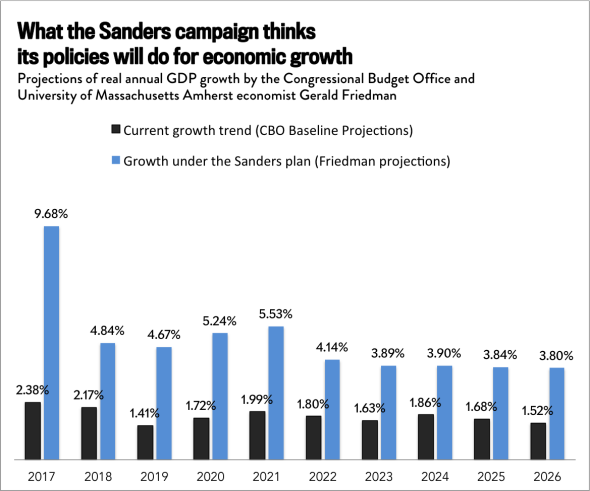

The latest kerfuffle is focused on an analysis by Gerald Friedman, a professor at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, which concludes that if Sanders passed his entire platform—including, among other bits, a $15 minimum wage, single-payer health care, a $1 trillion infrastructure spending bill, and new taxes to pay for it all—U.S. economic growth would rocket to an average of 5.3 percent per year over a decade. (Right now, we’re hovering just above 2 percent.) On its face, that number is very, very hard to take seriously and would set off alarm bells among most economists. The last time we hit 5 percent growth in a single year was 1984. Liberals (myself included) widely mocked Jeb Bush for promising to unleash 4 percent annual growth, partly because he vowed to do it mostly with tax cuts but also because it’s simply very, very unlikely that an advanced economy with an aging population can sustain that pace of economic expansion. Friedman’s forecast makes Bush’s look downright modest.

Sanders did not commission the Friedman report, but his campaign has embraced it. “Its gotten a little bit of attention, but not nearly as much as we would like,” Warren Gunnels, Sanders’ policy director, told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette last week. “Senator Sanders has been fighting establishment politics, the establishment economics and the establishment media. And this is the last thing they want to take a look at.” Gunnels also stood by the estimates in an interview with CNN, explaining, “We haven’t had such an ambitious agenda to rebuild the middle class since Presidents Roosevelt, Truman and Johnson.” When I called about Friedman’s paper on Wednesday, a Sanders spokeswoman said the campaign was sticking with its previous comments and didn’t have anything extra to add.

None of this is sitting well with the Democratic Party’s policy establishment. The letter criticizing Friedman’s analysis was written by Alan Krueger, Austan Goolsbee, Christina Romer, and Laura D’Andrea Tyson, all former leaders of the Council of Economic Advisers under Presidents Obama and Clinton. “As much as we wish it were so, no credible economic research supports economic impacts of these magnitudes,” it states. “Making such promises runs against our party’s best traditions of evidence-based policy making and undermines our reputation as the party of responsible arithmetic. These claims undermine the credibility of the progressive economic agenda and make it that much more difficult to challenge the unrealistic claims made by Republican candidates.” In the world of liberal econ, this is a bit like the Vatican ringing up a small church to chew it out for celebrating Mass wrong.

Other writers and economists have piled on, too. At the New York Times, Paul Krugman said Sanders’ embrace of 5 percent growth shows his campaign was just “not ready for prime time.” Brad DeLong at the University of California–Berkeley, wrote a post titled: “We Need to Hold the Line on Analytical Standards Here” (that counts as impassioned, I swear). Mother Jones’ Kevin Drum declared in a headline that the “Sanders Campaign Has Crossed Into Neverland.”

My instinct was, basically, to agree. But I also wanted to understand how Friedman was reaching his conclusions, and maybe get some insight into the Sanders campaign’s thinking. So I gave the professor a call.

What does this paper actually say?

Before we get into the macro-modeling thicket, a brief aside. I talk to a lot economists for my job, and few, if any, have ever struck me as so politically guileless as Friedman. He tells me he’s actually a Hillary Clinton supporter and donates to her campaign. (He prefers Sanders’ policy positions but thinks Clinton has a better shot at making progress on her priorities.) And while the professor had previously scored the cost of Sanders’ single-payer plan after being asked by the campaign—he’d done a similar analysis for the pro-single-payer group Physicians for a National Health System—the oh-so-controversial growth estimates were his own passion project. “I did it as a naïve academic,” he told me. Friedman ran the numbers by Sanders’ staff to make sure he had the details of their plans right, but that was the extent of their involvement.

All of which is to say, I think the man really made a good faith effort here.

On to the econ: To understand Friedman’s forecast, it helps to look at his projections year by year (sadly, those numbers aren’t in the main paper, but are in a separate file he’s been sending to reporters). Notice that in 2017, he thinks that Sanders’ raft of proposals would send U.S. real GDP growth spiking to 9.68 percent (currently, the Congressional Budget Office expects roughly 2 percent growth), which looks a bit like China back before things started going haywire, or the U.S. when it was bouncing back from the Great Depression. After that, there’s a sharp drop, and growth slowly drifts down to a bit below 4 percent—still an improvement over our current pace of growth, but not exactly 5 percent from here until eternity.

Jordan Weissmann

So what’s going on? It’s not stated clearly in the paper, but Friedman starts from the premise that the U.S. is still essentially in a depression—not in the sense that we’re staring at mass job losses and bread lines, but in the sense that the country is operating at far, far below its economic potential. As a result, he thinks a sufficiently massive amount of government stimulus spending could create a fast burst of growth, pushing the economy’s output back to where it naturally belongs and returning the U.S. to full employment.

By Friedman’s accounting, the first few years of Sanders’ plan would give us just that sort of a jolt. In 2017 alone—again, assuming Sanders can pass all his proposals—the country would get a roughly $400 billion boost from things like government infrastructure projects and increased consumer spending resulting from an increase in the minimum wage. It would get roughly another $400 billion injection due to single-payer, since Washington would start paying premiums before increasing taxes to cover them. Loosely speaking, it would be like dumping the entire Obama stimulus package on the country in one year.

Over time, Friedman thinks the push largely from government spending will bring the U.S. back to full employment. As the labor market gets tighter, the improved economy will attract more immigrants, expanding the size of the workforce, and employees will simultaneously become more productive. More people producing more stuff per hour will then sustain the relatively speedy pace of growth under President Sanders, even as things like tax increases take more of a bite.

Is that really so absurd?

The problem with Friedman’s forecast is that it involves a series of questionable assumptions that, stacked on top of each other, aren’t really credible.

Take his stimulus math. In general, economists believe that government spending is more effective at sparking growth—in academic speak, it has a higher “fiscal multiplier”—when the economy is weak than when it’s strong. If we’re in a severe recession, $1 of extra federal cash could create $2 or so in growth, as businesses rev back up and the unemployed return to work. But if the economy is already firing on all cylinders, that same dollar probably won’t lead to much extra growth at all, since there won’t be a lot of jobless Americans to hire or unused factory lines to turn back on. Instead, it’s more likely to bring about inflation, in which case the Federal Reserve would likely intervene by raising interest rates to slow the economy and keep prices from rising.

Friedman believes government spending could be enormously helpful at first because, again, in his view the U.S. is still stuck in a ditch. He told me he thinks the economy would be roughly $1 trillion larger if it were operating at its potential. The Congressional Budget Office, in contrast, thinks the output gap is about half that size, and its guess is on the high end. Even if Friedman is right on that point—and he might be, since estimating this stuff is tricky—he still assumes that new spending will have an fairly strong effect way past the point at which the economy should hit full employment in his model, when you’d expect the fiscal multiplier to be closer to zero. All the while, inflation averages 3 percent, which is above the Federal Reserve’s target, and yet the bank never steps in to cool things off. Both the inflation estimate, which still seems a bit low, and the idea that the Fed would stand pat seem like a stretch.

And it goes on. In order for more spending to grow the economy once you hit full employment, the U.S. either needs a larger or more productive labor force. Friedman argues that in spite of retiring Baby Boomers, the influx of ready-to-work immigrants he envisions will still boost the country’s employment-to-population ratio to 65 percent. That has never happened before. He also thinks productivity growth will average 3.2 percent per year, which the U.S. has also never managed on any kind of sustained basis in the modern era. His basis for that particular prediction is a concept known as Verdoorn’s law, which says that lower unemployment drives productivity higher. It’s a very interesting idea, but not exactly a mainstream one.

There are more bits to nitpick—Friedman’s estimates about the effect of minimum-wage increases on consumer spending growth seem atypically large, for instance—but you probably get the idea. In a vacuum, any one of Friedman’s predictions about productivity or the labor force or inflation might just seem a bit sunny. But in the end, he’s predicting one low-probability outcome after another. As Jared Bernstein from the liberal Center on Budget and Policy Priorities said to me, “When you throw all those assumptions together, they’re implausible.”

What does this mean about Sanders?

Again, the Sanders campaign didn’t hire Friedman to score its economic plan. But touting the results suggests his staff is less than dedicated to empirical rigor, or at least a bit too eager to accept unrealistically flattering forecasts about its own proposals. You know how conservatives often argue that tax cuts will mostly pay for themselves? This is the liberal equivalent.

Should anyone care? To state the obvious, absolutely nobody is voting for Sanders because they think his policy director has impeccable taste in economic modeling. He’s a values candidate. Likewise, nobody, outside of a few econ departments and offices in Washington, is really voting against Sanders because of arithmetic. People either buy into his incredibly idealistic brand of politics and utter focus on economic inequality, or they don’t. And frankly, that’s a fine way to judge your president.

If you are inclined to worry about the nuts and bolts of policymaking, however, this is all a little disconcerting. If Sanders is surrounding himself on the campaign trail with aides who are willing to indulge in magical thinking, you can’t help but wonder who will be advising him in the White House. In theory, paying close attention to empirical evidence and taking a skeptical approach to happy claims about future growth that would make your grand plans easier to finance should lead to better, more careful policymaking. It may just sound like a bunch of details. But when you’re trying to fundamentally reshape the world’s dominant economy, details matter.

Read more Slate coverage of the Democratic primary.