This post originally appeared in Inc.

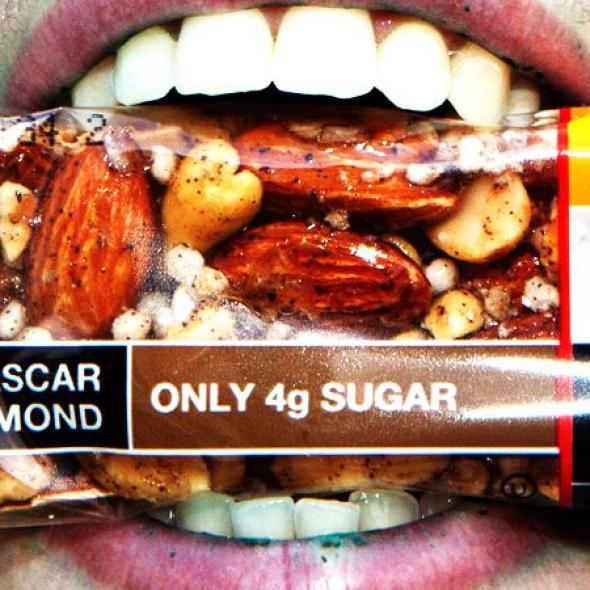

Kind is known primarily for its snack bars brimming with dried fruit, nuts, granola, and other ingredients, served up in a distinctive, see-through wrapper, suggesting transparency as well as health.

But since the spring, the company has been caught up in a quiet battle with the Food and Drug Administration over whether it can use the term “healthy” to describe some of its products and on portions of its website. While Kind has agreed to make changes to the offending labels, it is also firing back.

On Tuesday it sent the FDA what’s known as a citizens petition, signed by 16 experts, including nutrition professionals and doctors, urging the FDA to change its guidelines around fat, which it says have not been updated in more than 20 years, and which should include a greater allowance for healthy fats.

“At a minimum, we hope that this petition will spark a conversation that will help educate consumers about the importance of eating real foods and foods made with nutritionally-dense ingredients,” Kind founder Daniel Lubetzky said in an emailed statement.

In March, the FDA sent the New York–based company a warning letter saying its advertising was in some instances misleading, in part because the fat content of four of its bars is higher than the FDA allows for use of the word healthy.

An FDA warning is a big deal for any small company, let alone one that defines its brand entirely as being a healthy alternative to competing snack foods. Yet Kind’s response is a clever one, business experts say. On the one hand, KIND has cast itself as David to the FDA’s Goliath in a way that everyone likes to get behind, particularly other small-business owners who often despair about the number of federal regulations to which they must adhere. On the other hand, through its petition, it has also indulged in some creative rebranding, business experts say, which may allow the company to nudge the dialogue over healthy labeling into new territory.

“[Kind’s] main marketing is that they are a healthy snack, and that basically is what they’ve built their brand around,” says Bradley George, an associate professor of entrepreneurship at Babson College, who adds that the FDA warning letter is potentially a roadblock for a company that’s positioned its brand this way.

Certainly Kinc, an Inc. 5000 company founded by Lubetzky in 2004, can still be considered small. It has 300 full-time employees. And though it hasn’t publicly released revenues since 2012 when it noted it had $125 million in sales, it says revenues have doubled every year since it launched. The company has 50 varieties of bars, of which it sold 450 million units in 2014, according to a company spokeswoman.

Yet what Kind is going through has parallels, albeit in much higher profile examples from much larger companies, George says. In 2000, for example, BP, launched a campaign entitled “Beyond Petroleum,” to try to burnish its credentials as a company that supports sustainable energy, not only the drilling of oil. Tobacco company Philip Morris also underwent a similar transformation in the 1990s, to distance itself from its history as a cigarette manufacturer, rebranding itself as Altria.

The key difference, George says, is that these multibillion dollar companies have deep pockets for repositioning, whereas Kind does not.

“For younger [and smaller] firms, this is a little tougher because branding is expensive, and my guess is this is what the petition is about,” George says, adding that the petition is a relatively cost-free way for Kind to reposition itself with consumers.

Certainly there’s a yawning divide between Kind’s current dilemma and rebranding stemming from multibillion dollar settlements of much larger companies. Indeed, Kind’s case essentially boils down to a few grams of fat.

Currently the FDA claims that the term healthy may only be used for products with nutritional claims of 1 gram or less of saturated fat per 40 grams, and no more than 15 percent of calories from saturated fat.

The bars in question had between 2.5 and 5 grams of saturated fat, and rather than change its recipe, Kind will change its packaging in the coming months to remove the term “healthy” from the back panel of the bars, a company spokesman said.

Yet fat standards have changed significantly over the past two decades. And Kind hopes to make changing the FDA’s standards into something of a national campaign.

“It’s critical that the FDA reconcile and update these regulations so that they conform to what we now know to be true about healthy eating,” David Katz, a senior nutrition adviser to Kind, and founding director of Yale University’s Yale-Griffin Prevention Research Center said in an email. “There are some very nutritious foods that are part of optimal diets—including nuts, avocado and salmon—that may have a high inherent fat content.” Katz is one of the petition’s signers.

Kind is no doubt onto something, especially since it’s not the first company that has petitioned the FDA to change its labeling standards over the past few years. As Quartz reported in November, the Sugar Association, Sara Lee Corp., and the Grocery Manufacturers Association have all recently filed citizens petitions with the FDA over qualifications for the word “natural.”*

And that’s potentially all good for the way Kind hopes to continue marketing itself.

*Correction, Dec. 4, 2015: This post originally misidentified the Grocery Manufacturers Association as the Grocers Manufacturers Association.