Bernie Sanders famously likes to refer to himself a “democratic socialist.” Not content to label his views as merely liberal or progressive, the presidential candidate reaches all the way for the S-word, which has been basically verboten in post–World War II American national politics. This has led to some debate over what, exactly, a “democratic socialist” actually is, and whether one can accurately or usefully call the man any kind of socialist at all, given that his views actually line up quite well with those of many fairly mainstream members of the American left. The discussion has even sucked in the prime minister of Denmark, which Sanders has held up as a possible model for the United States. (Denmark, the prime minister would like us to know, is “far from a socialist planned economy.”)

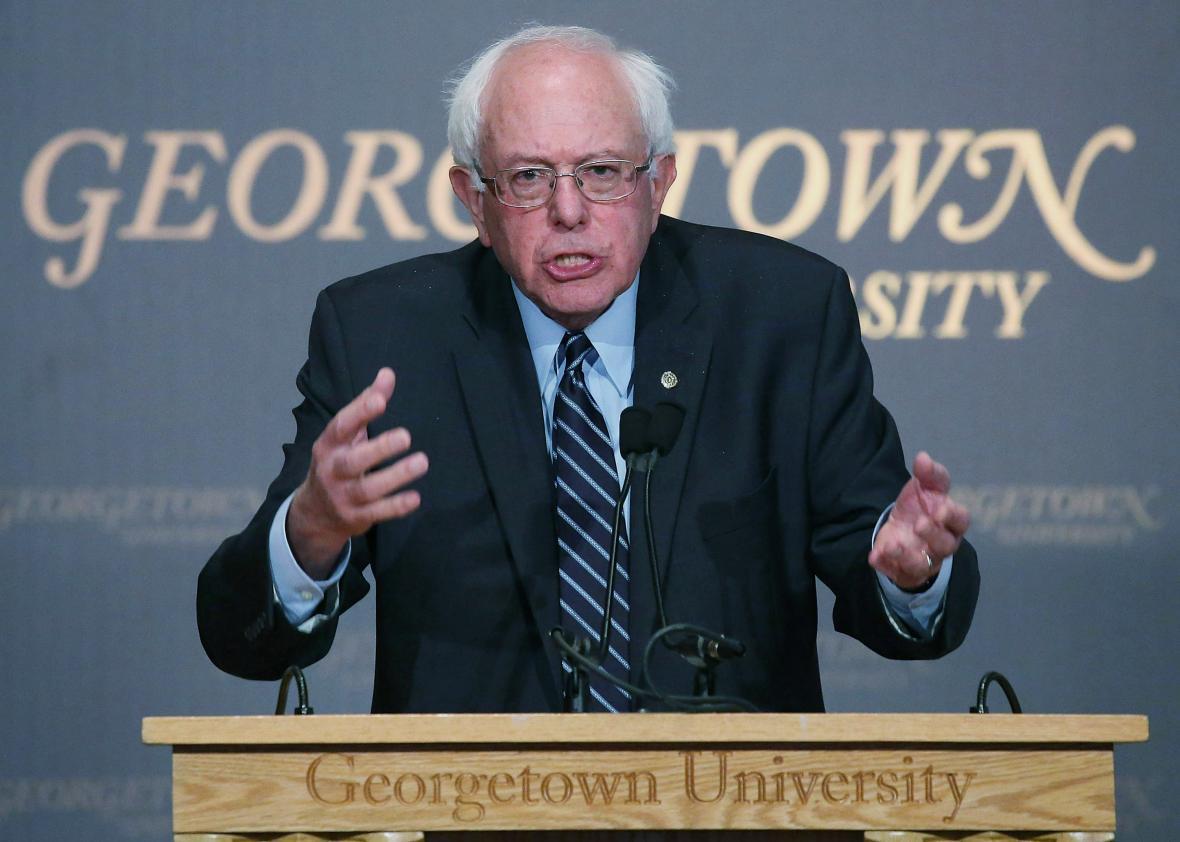

So Thursday, during at speech at Georgetown University, Sanders defined his terms. His talk didn’t contain any huge surprises. “I don’t believe government should take over the grocery store down the street or own the means of production,” he said, thus disavowing the strict Marxist definition of socialism with a dose of grandfatherly humor. “But I do believe that the middle class and the working families who produce the wealth of America deserve a decent standard of living and that their incomes should go up, not down. I do believe in private companies that thrive and invest and grow in America, companies that create jobs here, rather than companies that are shutting down in America and increasing their profits by exploiting low-wage labor abroad.”

In short, Sanders believes in a basic market economy with a large welfare state and a healthy amount of regulation. He would like a $15 minimum wage. He would like free tuition at public colleges. He would like the wealthy and corporations to pay more taxes. He would like single-payer health care.

Whether you think it makes strict sense to call all of this “democratic socialism” is obviously going to depend on your view of the term “socialism.” As I’ve written before, it’s certainly not what revolutionaries in 19th-century Europe had in mind, given that they very much wanted to seize the means of production. Bhaskar Sunkara, founder of the socialist magazine Jacobin, is upset that Sanders doesn’t emphasize “power” more in his formulation. But as Dylan Matthews has argued, it’s also fair to think of modern socialism as a reform movement that evolved from the hardcore Marxist parties of old, and decided to accept capitalism while sanding off its rough edges with a larger welfare state. In that view, the European social democracies that Sanders so admires are just socialism’s more mellow grandkids.

In the end, it’s not really useful to get bogged down in arcane arguments about terminology. Sanders uses socialist because it signifies that he wants to see fundamental changes in politics. He talks sincerely about a “political revolution” that will bring more Americans out to vote for their interests, and in that sense, take power. “When I use the word socialist, and I know some people are uncomfortable with it, I say it is imperative that we create a political revolution, that we get millions of people involved in the political process, and we create a government that works for the many, not the few,” he said during a question-and-answer session. It’s a lot easier to talk about “revolution” and distinguish yourself in the eyes of voters when you’re willing to rhetorically signify a hard break with the rules and mores of mainstream American politicking. And, given the way so many Democrats have responded, it’s turned out to be surprisingly good branding. Strictly apt or not, calling himself a socialist might have been one of Sanders’ smartest moves.