Who is Alan Krueger and why did his name come up when Bernie Sanders, Hillary Clinton, and Martin O’Malley were arguing over the minimum wage Saturday night at the Democratic debate on CBS? And is he a Wall Street crony like O’Malley suggested, or a progressive economist like Hillary said?

Krueger, the former chair of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers and a professor of economics at Princeton University, published a paper in 1994—along with David Card at the University of California, Berkeley—looking at the impact on employment after New Jersey raised its minimum wage in 1992. The two men studied hiring patterns at fast food outlets located near the border between New Jersey and Pennsylvania, a neighboring state that did not raise its minimum wage at the time. The result? No job loss for the New Jersey dining establishments. There was, in fact, a slight move toward more full-time work.

This was an unexpected result, to say the least. Economists believed jobs would be lost when the minimum wage was increased, because employers wouldn’t be able to afford to hire as much labor. Some have since performed other studies to show that raising the minimum wage does result in job losses. (As Annie Lowrey noted in the New York Times a few years back, “As always in economics, nobody seems to agree on anything.”) So, based on these other studies, the idea that job losses go up when the minimum wage does remains the conventional wisdom in conservative and Republican circles. Jeb Bush, for example, claimed a few months ago that an increase in the federal minimum wage would “make it harder and harder” for people to get on the “first rung” of the employment ladder. It was a big issue in the last Republican debate as well, with multiple candidates adamantly opposing minimum wage increases. (There is also the idea that a higher minimum wage will lead companies to send jobs to countries where they can pay employees less, which is what Donald Trump was referring to when he claimed “wages [are] too high,” in that debate).

On the other hand, supporters of the raising the minimum wage now use Krueger and Card’s work, in part, to make their case. Why wouldn’t they? As Matthew Yglesias put it a few years back in Slate, “The David card/Alan Krueger empirical study showing no negative employment impact from a minimum wage increase is famous because it showed what liberals wanted to believe.”

But what is too low and what is too high? Sanders and O’Malley both support the goal of a $15 an hour minimum wage that is being pushed by groups like Fight for $15 and put into practice in cities like Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. “You have no disposable income when you make 10, 12 bucks an hour,” Sanders argued on Saturday night. “When we put money into the hands of working people, they’re going to go out and buy goods, they’re going to buy services and they’re going to create jobs in doing that.”

But that only works if people remain employed. That’s where Krueger comes back in. Last month, he published an op-ed in the New York Times saying an increase of the minimum wage to $15 an hour could “risk undesirable and unintended consequences.” The reason? There is, Krueger said, “no international comparison” for an increase of that magnitude. We would be sailing into the unknown. “Although some high-wage cities and states could probably absorb a $15 an hour minimum wage with little or no job loss, it is far from clear the same could be said for every state, city and town in the United States,” he added.

Clinton said Krueger’s position is why she supports a $12 an hour minimum wage. “I do take what Alan Krueger said seriously,” she noted, adding that—like Krueger—she supported efforts by individual states and cities to raise their minimum wage.

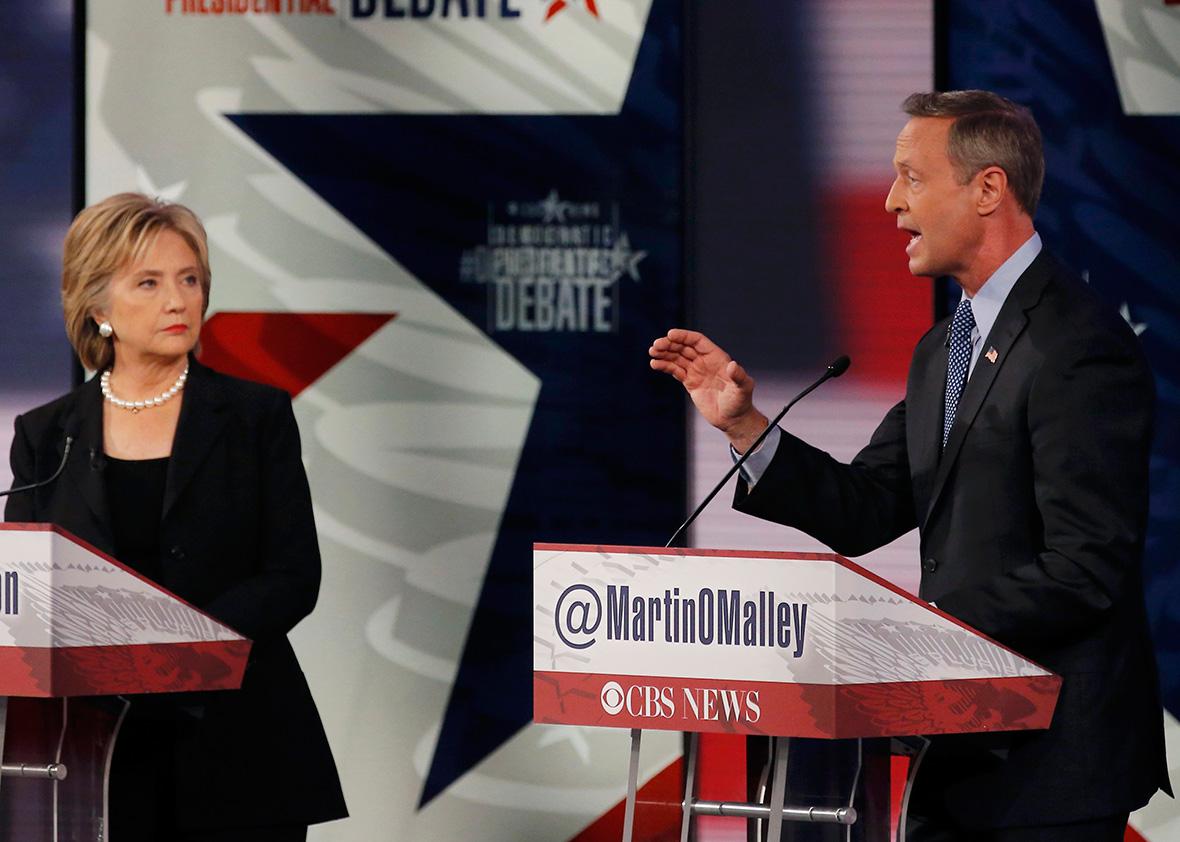

That’s when O’Malley jumped in with this attack: “We need to stop taking our advice from economists on Wall Street.” Hillary was quick to respond by defending the primary source for her argument: “He’s not Wall Street. That’s not fair. He’s a progressive economist.” And she’s right! O’Malley might not agree with Krueger, but he is wrong about his work history. No longer a member of the Obama administration, he’s now back at Princeton University. He does not work on Wall Street. And Hillary is right to note that Krueger’s old work formed the basis for the progressive case for increasing the minimum wage, which means it’s fair to ask progressives to listen to him now.