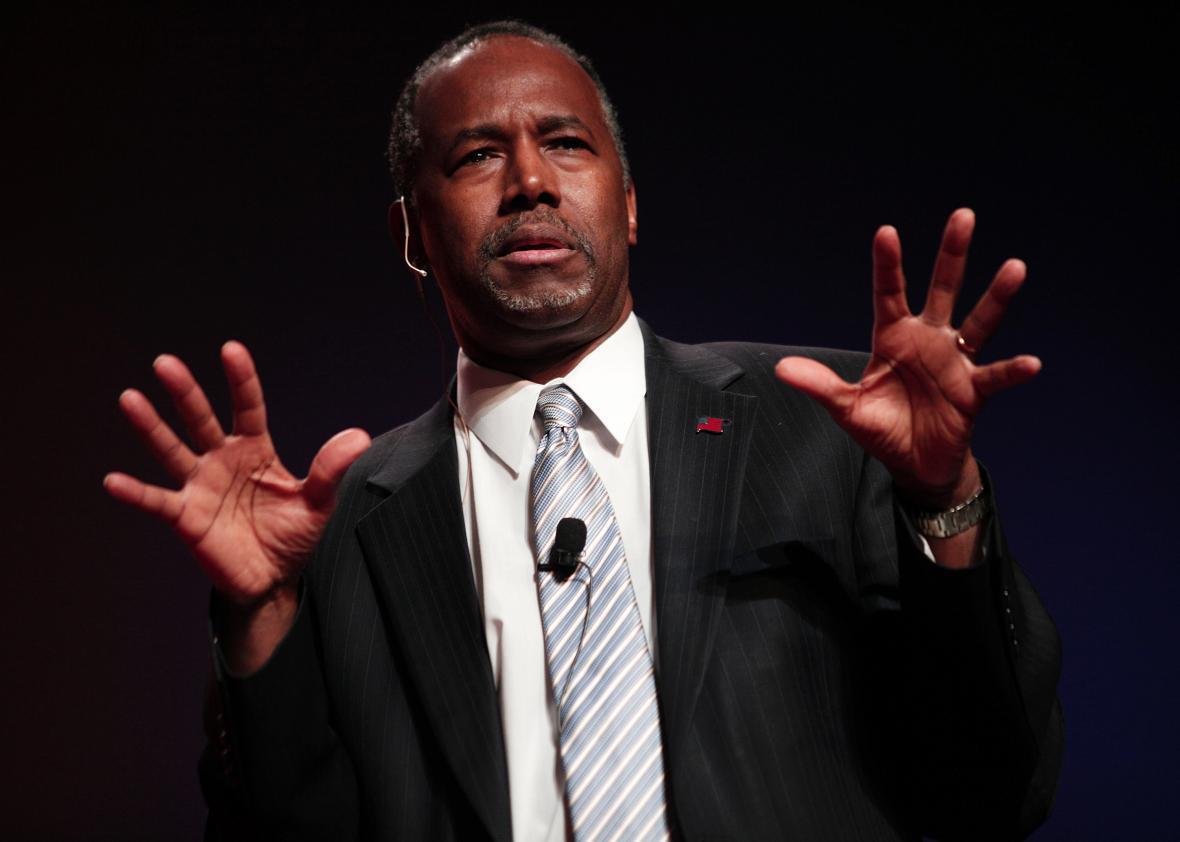

Retired neurosurgeon Ben Carson has risen to second place in the Republican presidential primary by presenting himself to voters as the accomplished, affable, soft-spoken face of conservatism’s lunatic fringe—the sort of guy who will suggest that evolution was influenced by “the forces of evil” (aka Satan), that there are meaningful parallels between the United States in 2015 and Nazi Germany, and that next year’s elections might just get canceled due to social unrest. With that in mind, his relative lack of expertise on subjects like the federal budget or monetary policy are neither the most shocking nor worrisome aspects of his candidacy, especially considering that the current GOP poll leader is the human embodiment of belligerent ignorance and even the established candidates have staked their runs on fantastical policy platforms.

Nonetheless, given that Carson is attempting to become president of the United States, it seems worth noting that he appears to understand little about how the government he would lead actually functions or relates to the economy. On Wednesday, Marketplace ran an extensive interview in which the candidate discussed his thoughts about economics with host Kai Ryssdal, and it makes for some harrowing reading. I’ve broken out a few of the takeaways.

Ben Carson Has No Grasp of the Federal Budget

Like many a candidate before him, Ben Carson thinks the federal government would be more effective if it ran “like a business,” which in his mind would mean applying some corporate management techniques, like Lean Six Sigma, to make it more efficient. Unlike most candidates, he seems to think this will eliminate the government’s deficit. Asked how he plans to balance the federal budget, as he has said he would like to, Carson explains:

What I would do is first of all, allow the government to shrink by attrition. Don’t replace the people who are retiring, thousands of them each year. And No. 2: Take every departmental head, or sub-department head and tell them, “I want a 3 to 4 percent reduction.” Now anybody who tells me there’s not 3 to 4 percent fat in virtually everything that we do is fibbing to themselves.

This is a preposterous answer. The Congressional Budget Office reports that last fiscal year, the federal budget deficit was $435 billion (which, by the way, was the lowest since 2007 and below the 50-year average as a percentage of GDP). If you were to cut all federal outlays, including Medicare, Medicaid, military spending, and social security, by 4 percent, you would save less than $150 billion. It is unclear, however, whether Carson actually thinks he would need to cut any entitlement program spending—when Ryssdal pressed him on this point specifically, Carson said he was in favor of an “across the board” cut, but then went back to talking about “fat” in departments, which isn’t typically how people discuss Medicare benefits, for instance. Meanwhile, the CBO believes that reducing the entire federal workforce by 10 percent through attrition would only save about $50 billion over a decade.

It is a popular delusion that Washington could solve its long-term fiscal issues by eliminating waste and inefficiency. The reality is that we spend a great deal of money on benefits for the elderly and the poor while maintaining a massive military; the government, as the joke goes, is basically an insurance company with an army attached. The fact that a semiserious contender for president doesn’t seem to recognize this is slightly dispiriting.

Ben Carson Does Not Understand What the Debt Ceiling Is

By now, you are likely familiar with the debt ceiling. By law, the Treasury is only allowed to borrow a limited amount to cover all of its obligations. Every so often, Congress has to vote to raise that amount, so that the government can pay its bills. Failing to do so would result in an economically catastrophic default, but in recent years Republicans on Capitol Hill have tried to hold the debt ceiling hostage by threatening not to raise it without policy concessions from President Obama, a trick that they pulled off somewhat successfully in 2011, and far less so in 2014. As of now, it appears the government will need to increase the borrowing limit again in November.

The essential fact in all of this is that raising the debt ceiling does not authorize new spending. It lets the government pay for old spending. Ben Carson does not seem to understand said fact. Here is his exchange with Ryssdal on the subject.

Ryssdal: All right, so let’s talk about debt then and the budget. As you know, Treasury Secretary Lew has come out in the last couple of days and said, “We’re gonna run out of money, we’re gonna run out of borrowing authority, on the fifth of November.” Should the Congress then and the president not raise the debt limit? Should we default on our debt?

Carson: Let me put it this way: if I were the president, I would not sign an increased budget. Absolutely would not do it. They would have to find a place to cut.

Ryssdal: To be clear, it’s increasing the debt limit, not the budget, but I want to make sure I understand you. You’d let the United States default rather than raise the debt limit.

Carson: No, I would provide the kind of leadership that says, “Get on the stick guys, and stop messing around, and cut where you need to cut, because we’re not raising any spending limits, period.”

Given the repeated showdowns over this issue, it is simply mystifying that Carson is still missing the distinction between increasing the budget and raising the borrowing limit.

Ben Carson May Not Understand Anything About Monetary Policy

As conservatives are wont to do, Ben Carson professes to be very worried about the federal debt. How come? For one, he cites the famous and controversial Reinhart-Rogoff paper that suggested countries with debts equal to more than 90 percent of their GDP tend to grow more slowly. Of course, later analysis of their data that corrected for things like spreadsheet errors and the influence of outliers found that the relationship between debt and growth was seemingly nonexistent, but at least Carson is just buying into a popular misconception.

Then there’s this: “You know, one of the things that happens with this level of debt is that it’s very difficult for the Fed to raise interest rates.”

Come again? Is Ben Carson really suggesting the Federal Reserve hasn’t raised interest rates because of the national debt? Why yes, yes, that appears to be the case. Asked about Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s performance, he says:

Carson: Well, you know, I’ve known Janet Yellen for a long time. We’ve served on boards together, and she’s a very intelligent individual, very responsible, and obviously is trying to do what she thinks is right. But she’s caught between a rock and a hard place, and I understand that. And that’s why I would tend to really put the emphasis on driving down our debt, because that’s how we begin to correct the problem.

I’m first going to reach for the most charitable possible interpretation here. Carson thinks debt slows down growth. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve hasn’t felt comfortable raising interest rates because GDP and job growth has been pretty tepid during these post-recession years. Therefore, Carson might think that if we erased the debt, we’d get higher interest rates.

That line of thinking would lead us back to the most fundamental problem with the Reinhart-Rogoff paper—it doesn’t really offer a convincing story to explain why a country’s total stock of debt would slow down its growth rate (theoretically, a country borrowing to finance a large annual deficit could force up interest rates and crowd out private investment, but that’s a somewhat different, if related, issue). In fact, it’s just as reasonable to think causation runs the other way—that countries with slow growth end up with high debts because they don’t collect enough tax revenue. The U.S. debt ballooned after the Great Recession, for instance, because of both stimulus spending and because IRS collections plummeted.

The less charitable possibility is that Carson thinks Janet Yellen is really just eyeing the federal debt when she’s contemplating a rate hike. Which is something nobody else anywhere actually believes.

Ben Carson Doesn’t Understand Inequality

One way in which Carson does diverge from the typical conservative line is that he professes to be very worried about inequality. But his explanations for it are bit strange. Whereas we know the income gap has been primarily driven over the long term by skyrocketing pay for successful professionals and corporate managers, he seems to blame a combination of low interest rates and regulations. Regarding the former:

Well it used to be that Joe the Butcher would take 5 percent of his earnings every week and put it into a savings account. And he would watch that grow over two, or three, or four decades. And by the time he was ready to retire, he was in good shape. Now, poor people and middle-class people really don’t have a mechanism to grow their money. The only people who can grow their money are people who have a certain risk tolerance. And those tend to be upper-income people who can utilize the stock market. And therefore you see that income gap growing.

Some of this is true to a limited extent. (Emphaiss on limited: In reality very few Americans, including the elderly, have ever gotten much of their income from interest on savings.) However, it really has very little bearing on the general story of inequality. Yes, the post-recession bull market helped the rich recover much faster than the poor, but that would have been the case even if Bank of America were offering a few extra percentage points of interest on its savings accounts. The real problem for middle-class and low-income families, both in recent years and the long term, has been relatively lackluster wage growth. And on this front, Carson has some odd thoughts:

The other thing that’s growing—that income gap, I think that’s a severe problem for us—are the numerous regulations, and every single regulation costs in terms of goods and services. It is passed on. But who is most adversely affected? Poor people and middle-class people. It doesn’t hurt the rich very much. So again, you see the buying power of the middle class and poor people going down. These things are increasing the gap.

So in Carson’s mind, the rising cost of living is fueling the income gap. This is a bit tangled. On the one hand, he does make a potentially solid point: Some regulations, like restrictive development and housing policies as well as pricy vocational licensing requirements, definitely make life more expensive for the poor and middle class. But those tend to be local and state issues, not federal ones. On the other hand, by definition, the cost of living can’t really explain much about the growing income gap, because inequality statistics are adjusted for inflation. And, contrary to what Carson says, inflation actually seems to affect the wealthy more severely than lower-income families.

The upshot is that Carson spends a lot of energy trying to come up with explanations for inequality that lend themselves to conservative solutions, like deregulation. But the results, however, are awkward.

You Know Nothing, Ben Carson

Again, none of this is quite so colorful as Carson’s talk of Nazis and Satan. But it’s disconcerting nonetheless. Carson is more genial, and given his storied career in neurosurgery, certainly smarter than Trump. But he demonstrates only the slightest bit more thoughtfulness when it comes policy, and an equally willful, talk-radio-ish disregard for math. Meanwhile, these two men combined are currently carrying about 40 percent of the Republican vote. It truly is the modern know-nothing party.