Greece, it seems, has finally locked up a bailout deal. In principle, at least. This morning, following an 18-hour negotiating session, the country agreed to terms with its European creditors for a package of aid worth up to €86 billion in return for more economic reforms and budget austerity. National legislatures will have to give their stamp of approval, but it seems like the world will soon officially get a break from wondering whether Greece will be able to remain in the eurozone.

A temporary break, anyway. If you’re the sort of person who was hoping never to hear the phrase “Grexit” ever again, the details of this rescue don’t seem especially promising. The problem? In order to pay its debts, Europe still expects Greece to run unrealistically large primary budget surpluses. Here’s how the Wall Street Journal sums it up:

Already this year, Greece will have to limit its primary budget deficit, which strips out interest payments on government debt, to 0.25% of gross domestic product—a tough call for an economy expected to shrink as much as 2.3%.

In 2016, the government will have to run a surplus of 0.5%, which has to go up to 1.75% in 2017. From 2018 onward, Greece is expected to run primary surpluses of 3.5% of GDP to help pay off its debt, which few advanced economies have managed to do for years on end.

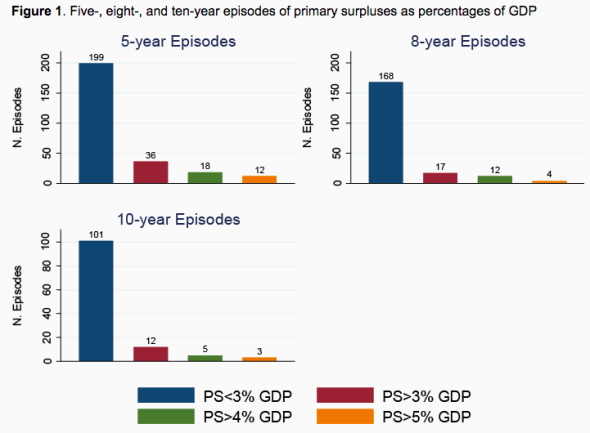

The International Monetary Fund has already derided the idea that Greece can run that large a surplus into the foreseeable future, and for good reason—countries rarely manage that sort of restraint, and politically, the ones that do tend not to look a whole lot like Greece.1 The most recent work on this issue comes from University of California–Berkeley economist Barry Eichengreen and Ugo Panizza of the Graduate Institute in Geneva, Switzerland. They looked at a group of 54 economies between 1974 and 2013 to find how many ever managed to run large primary surpluses for an extended period of time. It didn’t happen often. They were able to find just 36 instances in which a country managed to hit a 3 percent surplus for at least five years. There were just 12 in which a country managed to do it for a decade.

The countries that accomplished those amazing feats of fiscal prudence usually managed it under somewhat unusual circumstances. Ireland famously managed to slash government spending and tame its deficits in the early 1990s so it could qualify for eurozone membership, all without dashing its economic growth. But it was able to do so in part by devaluing its currency (which Greece can’t do, since it’s on the euro) to improve its exports and by turning itself into an international tax haven for large multinationals (again, not an easy trick to replicate). Norway kept its budget in the black with the help of copious oil money. New Zealand self-imposed massive budget and government reforms during the late 1980s and early 1990s that led to years of surpluses, but the lesson most economists have taken away from that episode, as Eichengreen and Panizza write, is that countries with a “strong rule of law, low levels of corruption and strong institutions and markets are in the best position to emulate its example.”

Suffice to say, that doesn’t exactly describe present-day Greece.

Eichengreen and Panizza also offer another reason why we should be skeptical about Greece’s ability to keep spending in check long term: Countries are more likely to pull off sustained surpluses “when growth is strong.” That makes sense: A stronger economy means more tax revenue and less stress on the social safety net. It also gives the government the political room to implement reforms, because people don’t suffer the same kind of pain that they do when you, say, cut their pension or welfare check in the middle of a recession.

Greece’s economy is expected to shrink this year. It’s expected to shrink next year. When it does begin to grow again, it will still be digging itself out from a deep depression, and the government is going to feel pressure to spend on the people who have spent the last several years suffering. Any debt deal that assumes otherwise seems destined to collapse under the weight of its delusions.

1Of note: Europe would like the IMF to help pay for this latest bailout, but the fund says it won’t chip in until Greece’s creditors offer it some debt relief, in order to make its burden sustainable. The eurozone’s leaders say they will discuss that possibility in the fall, according to the WSJ, but if the surplus targets are any hint, it doesn’t exactly look like they’re going to offer the scale of debt restructuring or forgiveness the IMF wants.