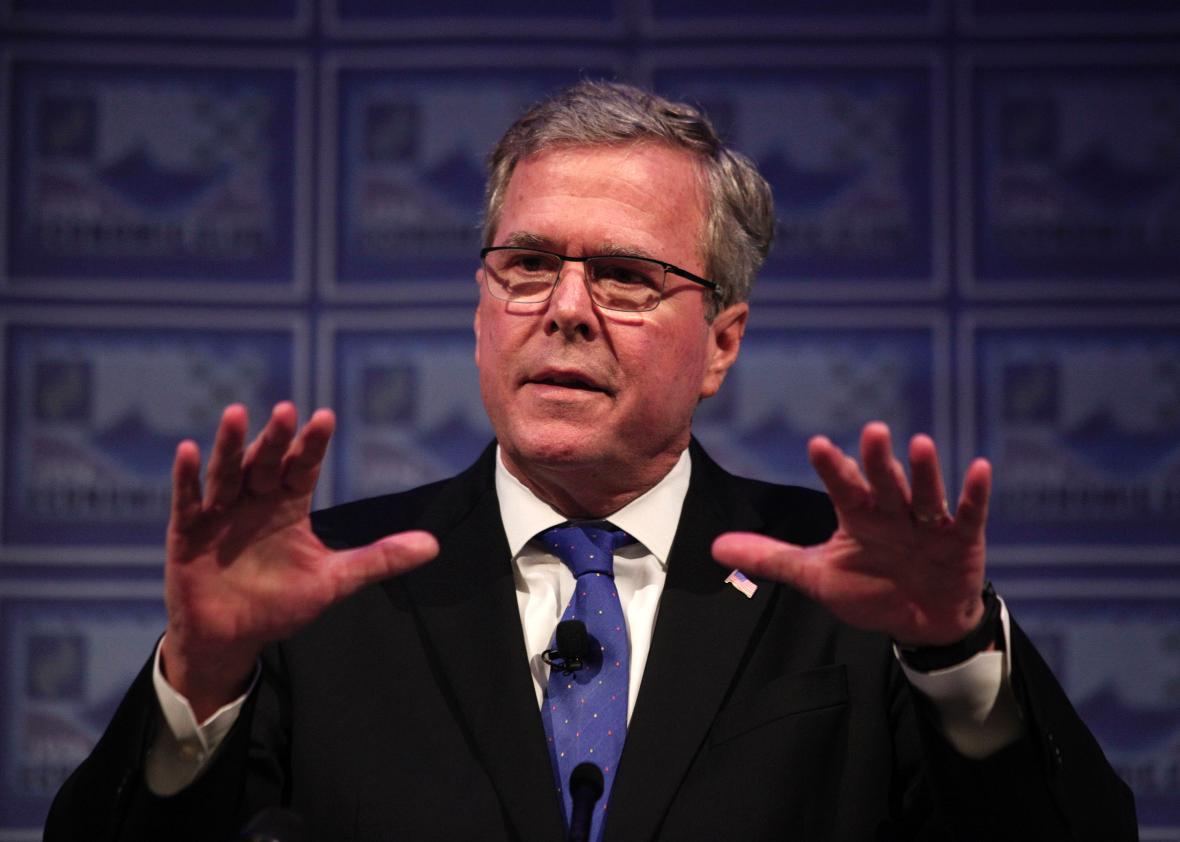

The fact that Jeb Bush isn’t prone to saying colorfully insane things about immigrants, the economy, or foreign policy may turn out to be his most important virtue as a Republican presidential candidate. Donald Trump natters on about Mexican rapists and John McCain’s war record. Scott Walker says he’ll tear up President Obama’s Iran deal on Inauguration Day. And Bush looks mellow by comparison. Meanwhile, he’s famously refused to sign on to Grover Norquist’s no-new-taxes pledge, and, unlike 2012’s crop of GOP contenders, said he’d trade $1 of revenue increases for $10 in spending cuts—which qualifies him as a pragmatist by conservative standards. His biggest misstep so far may have been suggesting that Americans will need to work longer hours if we want the economy to grow faster, which, a bit of outraged liberal chatter aside, wasn’t especially exciting.

So Bush has managed to clear the ankle-high bar of looking relatively adult in the quadrennial freak show known as the Republican primary. This is not the same, however, as demonstrating that his ideas are particularly thoughtful or moderate. While he breaks with his party’s rabid base on immigration and education, when it comes to the all-important issues regarding the size and role of government, his positions seem to be GOP boilerplate mixed with a dash of hardcore conservative fantasy, all dressed up with some rhetorical gimmicks. Bush might be the grown-up in the room. But you have to consider the room.

Take the speech Bush delivered Monday in Tallahassee, Florida, in which he outlined plans for shaking up Washington. First on his to-do list: a balanced budget amendment. This is the sort of idea that has somehow transformed into a mundane perennial of our political discourse, even though it is, in fact, an objectively radical concept that would deeply alter just about everything about how our government and economy function. This is in part because it is also treated as a harmless flight of fancy. Constitutional amendments, after all, are not really proposals. They are shiny objects politicians dangle in front of supporters whose intelligence they don’t particularly respect, because passing legislation that requires a two-thirds majority in Congress and ratification by the states is not something that happens in a polarized political environment. But by rehashing this old trope, Bush is acknowledging, albeit in the most boring possible way, that he shares the Republican base’s radically austere vision of government.

Next, Bush would like a line-item veto to make it easier to scratch out supposedly wasteful spending programs. The trouble is that the Supreme Court struck down the original line-item veto, which gave the president unilateral power to nix budget items, as unconstitutional back in the 1990s. Paul Ryan has proposed a watered-down, “constitutionally sound” version, which would basically help the president to suggest specific cuts for Congress to vote on. While not exactly a sea change, it would tip the legislative process further in favor of those who favor budget cuts.

Like many conservatives, Bush is also convinced that the 2.1 million-strong federal workforce is a bloated and wasteful bureaucracy that should be trimmed. And so, like others have proposed before, he wants to reduce its size by 10 percent over the next four years through attrition. For every three employees who retire, he would only allow agencies to hire one new staffer. That’s roughly 200,000 jobs, spread without rhyme or reason across the federal government. Inexplicably, Bush says the reductions would save billions of dollars “without adding to unemployment,” which is pretty obviously untrue in the short-term, since cutting back on government hiring will reduce the number of new jobs available each month.

What else would Bush like to do? This is where things largely turn to inane anti-establishment posturing (as can only be delivered by the establishment GOP’s favored candidate and relative of two former presidents). Bush says he would try to limit the influence of lobbyists in Washington, in part by making it harder for former lawmakers to go through the revolving door. This might seem more sincere coming from a man who wasn’t presently raking in donations from K Street. He also wants to fine Congress members who miss votes. Because the big problem with Capitol Hill is apparently that members aren’t there to vote on repealing Obamacare yet another time.

The same way Bush’s deeply conservative positions on federal spending are orthodox enough so as not to arouse much controversy, his proposals for ethics reform are banal and unrealistic enough not to generate outsize attention. The same goes his bumper-sticker-ready goal of magically achieving 4 percent economic growth every year, which is sort of the public policy equivalent of making a New Year’s resolution to lose 25 pounds by beach season. Is it silly? Sure. But not in an extravagant, headline-grabbing way.

And that’s sort of the name of the game for Bush. To win the presidency, he needs to present himself as acceptably conservative to his party without alienating mainstream voters or the media. And so he seems to be signaling his bona fides through the dullest means possible, while filling space with meaningless inspirational talk about growth and changing how Washington does business. This also fits the Republican Party’s needs rather well. As Jonathan Chait has pointed out, Republican party activists would be completely happy electing a cipher for president as long as said nonentity is willing to sign a version of Paul Ryan’s slash-and-burn budget. Bush, who has praised the Ryan budget, is positioning himself as the perfect empty suit for the job.