On Thursday, Uber filed a motion to oppose letting a major lawsuit that could undermine its business model proceed as a class action. The suit, which argues that Uber has misclassified its drivers as independent contractors when they are in fact employees, could have huge ramifications for Uber’s worker structure as well as the entire “sharing” or “1099” economy. Uber is very rich, with billions upon billions of dollars of funding, and so far very successful. But a ruling that its drivers should be considered employees could unleash a cascade of new and quite expensive costs, such as health benefits and reimbursement for on-the-job expenses like gas. It would also open Uber up to lots more liability, as drivers would gain the legal protections afforded to traditional employees.

Not surprisingly, Uber is going all out to fight this potential doomsday scenario. And in a 52-page filing, the company, which is being represented by attorneys at Gibson Dunn, lays out its arguments against treating the case as a California class action covering 160,000 current and former Uber drivers.

At the heart of Uber’s arguments is the notion that, fundamentally, there is no such thing as a typical Uber driver, and so lumping the concerns of 160,000 together would be entirely wrong. The plaintiffs “based their motion on a facially implausible theory that each and every one of these individuals had an identical relationship with Uber and has been misclassified as an independent contractor,” the filing states. To support this, Uber first notes that its drivers in California (and in the rest of the country) operate under one of 17 different licensing agreements. The various agreements evolved both as Uber revised its terms over time and at the discretion of local teams in different cities, and they differ in some fairly substantial ways. Some contain an arbitration provision; others do not. Some prohibit the driver from accepting tips; others don’t. Perhaps most crucially, some give Uber and its drivers the mutual right to terminate their relationship “without cause,” while others reserve that right unilaterally for Uber.

The arguments against a typical Uber driver don’t stop there. Uber also insists that every driver on its platform has a unique relationship with the company. Alongside its motion against the class action, Uber has filed a 102-page declaration from UC–Berkeley law professor Justin McCrary that repeatedly and somewhat tediously makes just that point. McCrary, who says he was paid his “standard billing rate” of $750 an hour for the report, spends about half of his pages detailing all the different ways that Uber’s drivers choose to use the “lead generation platform.” As McCrary explains, citing liberally from declarations made by Uber drivers, those working for the service include people who used to be taxi drivers, people who drive for multiple apps at once, people who also work part-time jobs, people who came out of retirement to drive for Uber, and people who subcontract out to other drivers. Because Uber allows drivers to set their own schedules—a point the company has emphasized throughout this case—McCrary adds that they have great control over when and where they accept jobs, and “highly individualized work circumstances.”

Uber has gone to great lengths in its motion to dismiss the idea that many drivers are required to accept a certain percentage of rides—often upward of 85 or 90 percent—or else risk deactivation. A policy like this could be construed as employer-like control on Uber’s part. “Many agreements provide drivers with unfettered discretion ‘to accept, reject, and select among the Requests received via the Service,’ ” the motion states. Similarly, it’s been reported that Uber will deactivate drivers who fall below a certain threshold on the company’s five-star rating system. To this point the motion contends, “several agreements incorporate no policies with respect to Uber’s star rating system.”

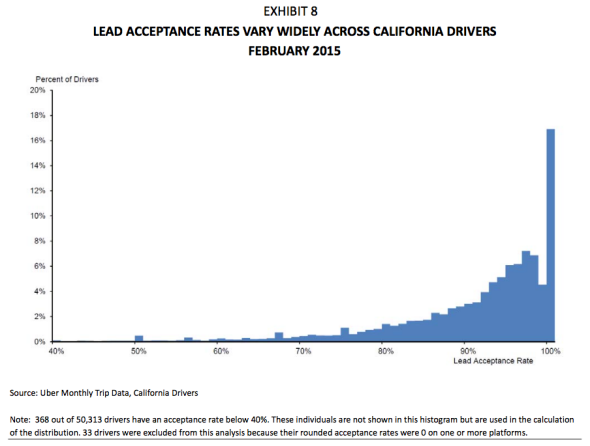

What’s interesting is that when you look at one of the charts in the McCrary report, ostensibly showing how “lead acceptance rates vary widely across California drivers,” a striking majority of them are accepting upward of 85 or 90 percent of rides. That could be because drivers tend to log onto the platform when they want to work, and from there accept a high percentage of jobs. On the other hand, it could be because most of Uber’s drivers have at one point or another been told that if they don’t accept a minimum percentage of rides, they’ll lose their access to the app. The first explanation supports Uber’s argument that its drivers are entrepreneurial independent contractors; the second suggests the company is exerting more control than it would like to admit. A spokeswoman for Uber said that the minimum acceptance rate “varies by city” and that drivers who don’t wish to accept trips “can simply log off the app.”

Uber filing

Much of Uber’s motion and McCrary’s declaration fits that pattern: They are filled with seemingly damning statements and facts that omit small yet crucial details. With the 17 different driver arrangements, for example, it’s unclear whether they all still exist because they need to, or because it’s now a convenient legal defense against a class action. (Uber’s spokeswoman said the company is not interested in moving all its drivers to the same agreement, calling the various forms “natural in the evolution of a company’s life.”) Uber also says drivers, like independent contractors, are able to “negotiate” for higher rates by strategically accepting rides during surge pricing and requesting “fare adjustments” when necessary—but it doesn’t say how often those requests actually occur. It’s also worth pausing briefly over the company’s use of “lead generation,” which is presumably a strategic pivot from “ridesharing,” “transportation network company,” and other terms Uber has used to describe its service in the past. A “lead generation” service sounds much less like an employer.

At the same time, Uber is right that the hundreds of thousands of drivers who use and have ever used its service don’t all do so in the exact same way, or for the exact same reason. The company has collected statements from more than 400 drivers, many of whom say they would not still work for the service if they were considered employees. “Plaintiffs seek a remedy—an employment relationship with Uber—that irreconcilably conflicts with the interests of countless drivers, and that could even subject a substantial number of drivers to legal liability or the loss of a job,” the motion states. Were drivers found to be employees, it “could force Uber to restructure its entire business model, thus jeopardizing the very attributes (e.g. flexibility, autonomy) that make the Uber App so appealing to drivers.”

To some drivers, sure. But certainly not to all—because then that would be typical. And there is no typical Uber driver. Remember?