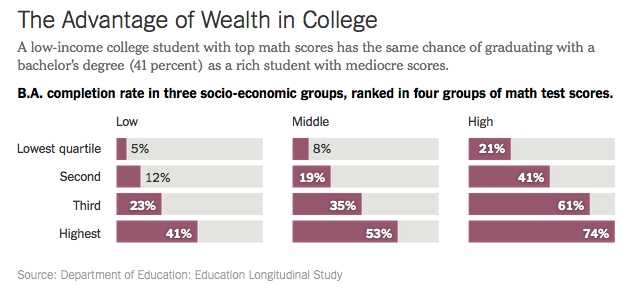

In case you needed a reminder that the deck is stacked against poor kids in this country, University of Michigan professor Susan Dynarski has offered a simple and grim illustration of that fact at the New York Times. In 2002, the Department of Education began tracking a large, nationally representative group of high school sophomores, whom it tested for math and reading skills. Ten years later, the agency found a troubling, though not exactly surprising, pattern. At every level of academic ability, the low-income students were less likely to finish college than their wealthier peers. Yet more depressing: Exceptionally smart poor kids, whose math scores ranked them among the top quarter of the study’s participants, were no more likely to attain a bachelor’s degree than scholastically middling rich kids.

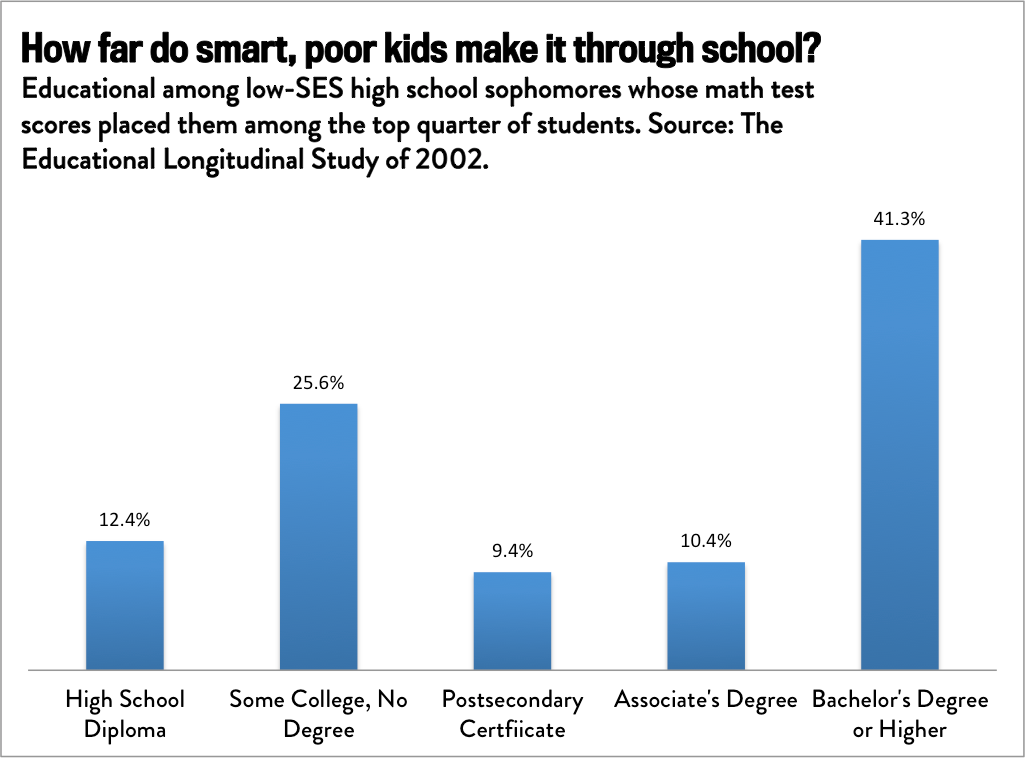

What happens to these bright, low-income students? It’s not so much that they don’t attend college—only 12.4 percent skip higher ed entirely. The problem is that most don’t finish, or settle for less than a bachelor’s degree, which of course limits their earning power later in life. Sometimes they try to save money on tuition by attending community college, even though most two-year schools have a spotty track record when it comes to helping students graduate. Sometimes they get lost or overwhelmed in a college’s bureaucracy, because they don’t have educated parents who can help guide them along. Sometimes they try to work through school and simply can’t balance the demands of a job with their academics. For one reason or another, they don’t make it as far as their talent suggests they should.

Jordan Weissmann

Part of the problem is our free-for-all college application process. Economists have found that most high-achieving, low-income students don’t apply to any selective colleges, even though those schools may be more likely to give them financial aid, or offer them the academic support they need to graduate. The reasons why these kids undersell themselves aren’t crystal clear. But it’s likely a combination of the fact that many of them attend poor high schools where few students aim high and college counselors rarely encourage them to, while at the same time, colleges don’t try particularly hard to find or recruit them.

But even at “good” schools, these students don’t always get the help they need. In their revealing book Paying for the Party, sociologists Elizabeth Armstrong and Laura Hamilton documented the ways that one large state flagship university sacrificed the needs of poorer undergrads in order to cater to the desires of mediocre but wealthy students looking to spend four years tailgating and doing keg stands. They found that without much in the way of institutional guidance or support, some ambitious low-income student flailed and then dropped out.

There’s another sad fact that underlines all of these issues. High-achieving, low-income students are rare. The Department of Education found that slightly less than 10 percent high schoolers from poorer families had top math scores, compared to 48 percent of those from wealthier backgrounds. Not many people can overcome poverty to excel academically. And we’re failing far too many of those kids who do.