Norway’s $900 billion sovereign wealth fund may soon have to drop its investments in the coal industry, thanks to a new set of rules making their way through the country’s parliament. Starting next year, the fund would be forced to pull its money from companies such as mining firms or utilities that make at least 30 percent of their revenue from coal, according to the Associated Press. The law received bipartisan support in committee and is widely expected to pass during a final vote early next month.

This is a notable victory for climate change activists who have been lobbying institutional investors to divest from fossil fuels. A number of university endowments and foundations have already joined the cause, but Norway’s sovereign wealth fund is the globe’s largest, laying claim to roughly 1 percent of all the world’s stocks and bonds. Environmentalists just landed a very, very big ally in their crusade.

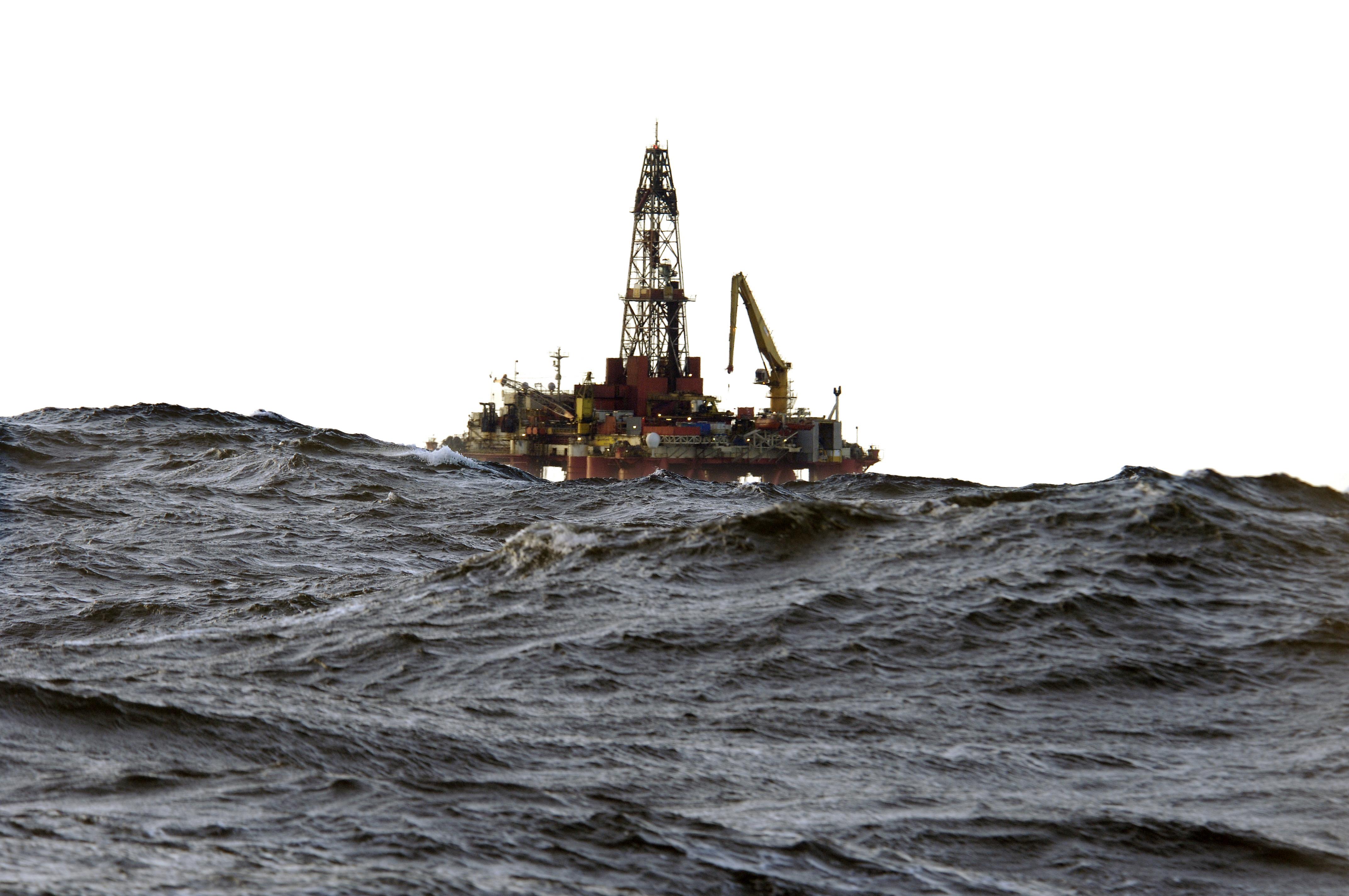

The turn of events is also a little ironic. Norway’s sovereign wealth fund is sometimes referred to as its “oil fund” because it was created in order to manage the country’s substantial petroleum revenues. Thanks to its extensive offshore oil resources, Norway is among the world’s biggest crude exporters, which makes the business of drilling up and shipping out fossil fuels a large and critical part of its economy. Some Norwegian politicians have seemingly attempted to get around the cognitive dissonance by pointing out that coal is an especially noxious contributor to climate change—“Coal is in a class by itself as the source with the greatest responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions,” said one member of parliament—but there is at least a little humor here.

It’s worth dwelling on the exact message Norway is sending with this gesture because, in the end, divestment movements are mostly about public relations. As Rebecca Leber recently explained at the New Republic, there is scant evidence that these campaigns harm their targets financially. And even in the land of hypotheticals, it’s hard to imagine a scenario in which they ever could. Most investors are relatively amoral when it comes to where they park their money. So even if some get queasy about an industry like tobacco or fossil fuels and decide to divest, there are plenty more out there in the market who will be willing to buy, especially if share prices are only being driven down for essentially political or idealistic reasons. If worst comes to worst, a corporation could just start buying back its own shares to prop its price back up (which they do plenty of already).

That’s why the real goal of divestment is to politically stigmatize an industry—to demonstrate that some businesses are so reprehensible that colleges and even entire countries feel the need to avoid investing in them, even if it means accepting slightly smaller profits.

What’s going on in Norway is a tiny bit different, however. There, some politicians, and even the sovereign wealth fund’s management, have played up the idea that they need to reduce the amount of “climate risk” in the country’s portfolio. The idea is that the world can only burn a limited fraction of its fossil-fuel reserves before the earth’s temperature rises to dangerous levels, and any concerted action to reduce greenhouse emissions could end up leaving a whole bunch of oil wells and coal veins completely valueless. So, in order to avoid holding on to a bunch of stocks that will suddenly be worth bupkis when the globe gets around to serious carbon regulations, Norway needs to wind them down now. In that light, the idea of an important oil exporter ditching coal investments seems a bit less laughable—the country just wants its fiscal future to be a little less tightly hitched to the fortune of fossil fuels.

Unfortunately, it’s difficult to tell whether the professionals charged with managing the wealth fund sincerely believe this. On the one hand, the fund indeed nixed 32 coal companies from its holdings in 2014, citing the threat of climate regulations. On the other, it’s been accused of quietly increasing its overall investment in coal while merely paying lip service to divestment. And although the fund says it’s actually been unloading its coal holdings in recent quarters, the fact that Norway’s parliament is forcing its hand through legislation muddies the picture a bit.

In any event, there is now a global oil power that officially wants to wash its hands of the coal business. The reasons might just boil down to the fact that politicians want to send a message about climate change, or they might also involve a dose of economics. Make of it what you will.