There’s been a lot of attention focused on the welfare reform bill that legislators in Kansas passed last week because it was such an obviously demeaning jab at the poor. Along with strip clubs, casinos, liquor stores, and cruises ships, it bans families from spending cash benefits at movie theaters or swimming pools—as if we should consider it a moral outrage for an impoverished parent to take her kid swimming because she relies on government help. The law would also stop beneficiaries from withdrawing more than $25 of their aid in cash each day, a rule that exists in not one other state. Originally, the limit was going to be set at $60, but legislators for some reason settled on the lower figure, despite the fact that ATMs don’t usually give out $5 bills. In Topeka, making life harder for the needy apparently didn’t involve a great deal of thought.

Still, keeping the poor out of the local AMC theater wasn’t really the main point of the bill. In the end, the law was mostly designed to kick more Kansans off of cash assistance altogether, in part by lowering the maximum length of time that families could receive help from 48 to 36 months. That’s not as colorfully vicious as telling parents that it’s a crime to take their kid to go see Cinderella, but in the grand scheme of things, it’s the much more important change.

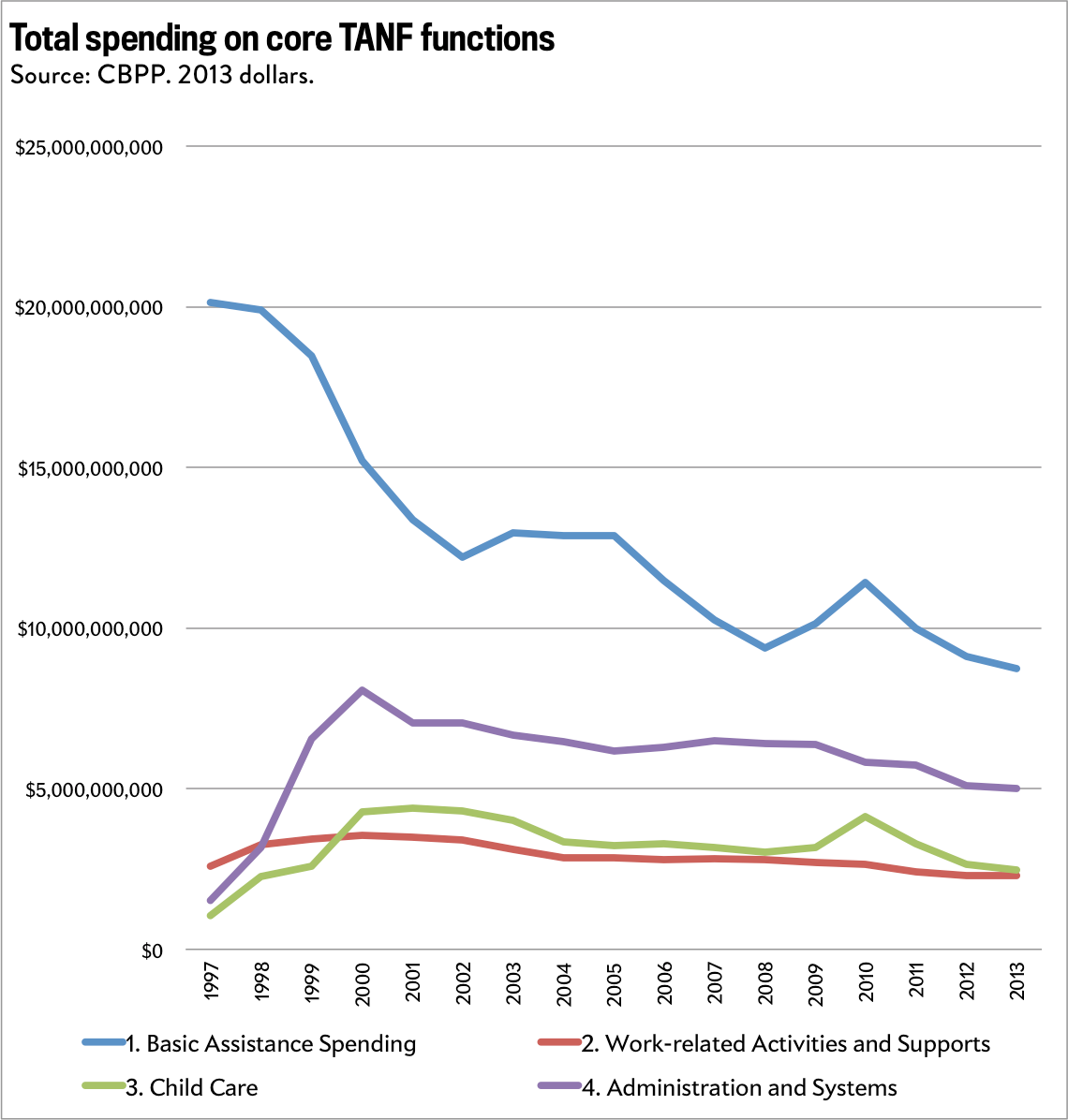

It’s also in keeping with a national trend. States today spend far less on cash aid to the poor than they did when Bill Clinton signed welfare reform and created the modern Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program. That was part of the plan. Clinton’s legislation was meant to give states more freedom to experiment with moving low-income parents from welfare to work and allowed them wide latitude to run their versions of TANF as they saw fit. At first, that led them to dedicate more resources to things like child care and helping jobless adults find work. But spending on those efforts peaked around 2000 and has more or less gradually shrunk once you account for inflation.

Chart by Jordan Weissmann

And there’s a very good reason for that. The federal block grants that help fund today’s welfare program aren’t adjusted for inflation, meaning that they’re worth a little less to the states every year. As a result, lawmakers have an incentive to gradually weed out beneficiaries to preserve resources. Worse yet, because of the somewhat loose guidelines governing how TANF dollars can be used, some governors may be tempted to divert the program’s funding in order to fill their states’ budget holes. As the Center on Budget Policy and Priorities notes, about one-third of the program’s money is now devoted to a diffuse category of activities they refer to as “other,” which covers things like child welfare services and early education—things that states might well fund anyway, whether or not TANF existed. Money saved on cash assistance is money that can be spent on those functions instead.

There have been some positive changes in welfare over the past 15 years. Many states, including Kansas, are using an increasing portion of their funds to buttress their own versions of the federal Earned Income Tax Credit, which boosts pay for low-wage workers. But ultimately, the pot of money devoted to helping needy families find work or support their families while they look is being whittled down. In the future, you’re not just going to see more states trying to make life harder on the poor. You’re going to see more states simply turning their backs on them altogether.