From time to time, you’ll hear economists argue that the best long-term solution to economic inequality is education. There is an enormous, and growing, pay gap between those with a college degree and those without. Push more people further through school, the thinking goes, and you’ll close the divide. MIT’s David Autor has pressed this point recently. And even though he’s better known for advocating a global tax on wealth, so too has Thomas Piketty. “So at the end of the day, the main policy to reduce inequality is not progressive taxation, is not the minimum wage,” the author of Capital in the Twenty-First Century has said. “It’s really education. It’s really investing in skills, investing in schools.”

What these analyses usually lack is a clear picture of what the world might look like if we successfully increased college graduation. But today, economists Larry Summers, Melissa Kearney, and Brad Hershbein have stepped up to offer an answer in a short paper for the Hamilton Project. The team finds that, yes, boosting bachelor’s degree attainment would slightly decrease inequality, mostly by bringing lower-income workers a bit closer to the middle class. But it wouldn’t do much at all to shrink the growing gap between the very rich and everybody else. In other words, if you’re worried about the power of the 1 percent (or .1 percent), expanding higher ed isn’t the solution you’re looking for.

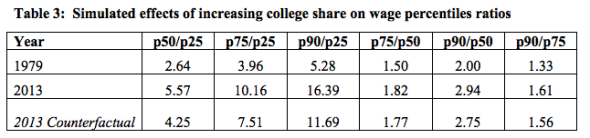

In their analysis, Summers, Kearney, and Hershbein run a simulation in which they give a bachelor’s degree to 1 out of every 10 working-age men who never went to college. “To be clear, this would be a tremendous accomplishment,” they write. “It is only slightly less than the observed increase in the college share over the entire 34-year period of 1979 to 2013.” What happens as a result? First, overall pay for college graduates goes down, since there are more of them on the labor market. However, all those new degree holders would see their own pay go up substantially. As a result, total earnings would ultimately rise, with bigger gains going to those near the bottom of the income ladder than those near the top, and the distance between low-earners and the middle class would shrink. According to the paper, the median American would earn about 4.25 times as much as someone at the 25th percentile, as opposed to 5.57 times, like they do today. The middle and upper-middle class would be crunched closer together, as well.

Hamilton Project

But income distribution would still be extremely uneven across the economy. The researchers find that the U.S. Gini coefficient—a standard measure of inequality—would barely drop, slipping from 0.57 to 0.55. The reason, Hershbein told me, is that the richest Americans would continue to take home an incredibly outsized chunk of the national paycheck.

In some ways, Summers, Kearney, and Hershbein may be too optimistic about the impact of education on inequality. For instance, their model assumes that as the number of college graduates rises, all current bachelor’s holders would see their earnings fall by about 9 percent. That seems a bit unrealistic. If more students start finishing degrees at average four-year schools, it might bring down their classmates’ pay. But I doubt those same B.A.’s will be competing for jobs with the alums of selective institutions. Brooklyn College grads might feel the pinch. High-earning engineers who went to Georgia Tech might not.

Another slightly technical but important point: The researchers assume that their new batch of graduates will be a completely random assortment of students from across the whole income distribution. That, too, seems a bit far-fetched. If extra Americans start graduating from college, they’re more likely to be middle class than poor.

All that said, the broad strokes of this paper are useful. Expanding educational opportunity could, theoretically, be a way to increase standards of living and make the country slightly more egalitarian. It just wouldn’t do much about the rise of the very rich.