Conventional wisdom says that working-class men have less earning power today than they did in the 1960s and 1970s. You’ve read the story plenty of times. Factory jobs were replaced by poorly paid service sector work, leading to a somewhat steady decline of wages for the bottom half of male earners.

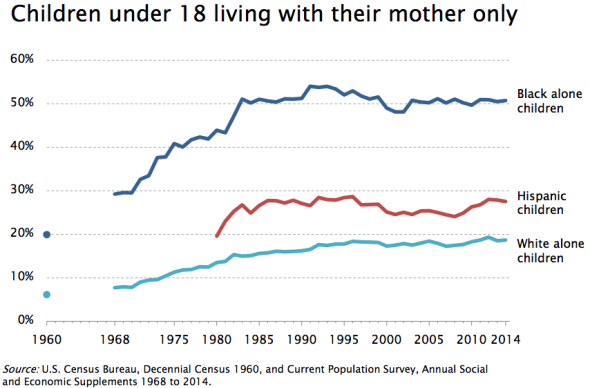

This narrative is a key part of how liberals tend to explain the dissolution of two-parent families over the past half-century. As men lost the ability to fill their old roles as breadwinners, traditional family structures disintegrated. Financial strains kept young couples from marrying, but not from having children, and women—who were entering the workforce and earning more—became wary about wedding fathers who seemed unable to deliver steady paychecks. Thus, the theory goes, we got the dramatic rise of single-motherhood.

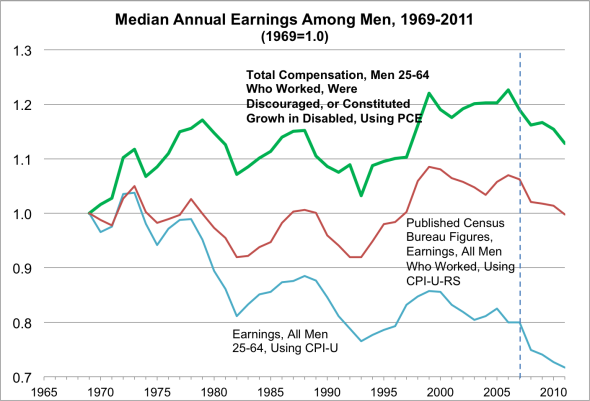

Some conservatives say that this tale is basically a fiction, and this week, as writers have been debating the sources of social decay in blue-collar America, both the Manhattan Institute’s Scott Winship and the New York Times’ Ross Douthat have raised some statistical objections to it. If you look reallllly carefully at the data, they argue, men’s incomes have not in fact declined by much, but instead are more or less flat over time. Aside from arguing about how to appropriately adjust income figures for inflation, they note that more low-income workers today are Hispanic than in the middle of the 20th century. And even if they don’t make much, some of those men are, in fact, far better off than their immigrant fathers. For non-Hispanic men, meanwhile, “the experience of the last four decades looks much more like stability than loss,” Douthat puts it.

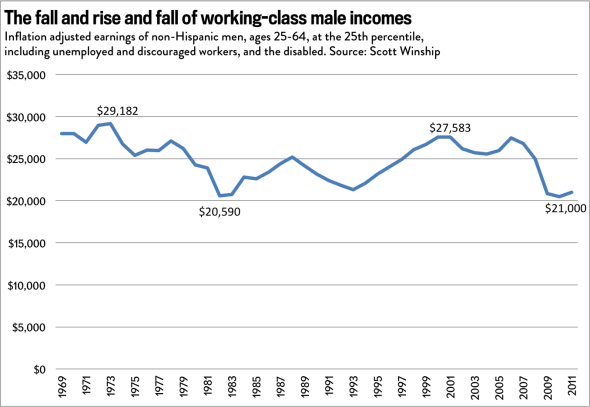

I might not use the word stability. Winship was kind enough to send me his data series, which I used to produce the graph below. In his post, he notes that if you “compare 1969 to 2007, earnings at the 25th percentile among non-Hispanic men rose 7 percent.” While that may be true, his comparison masks the fact that the 1970s and 1980s were a time of relative economic turmoil for that slice of workers. Their annual pay fell 29 percent from 1973 to 1982. It recovered a bit during the later Reagan years, only to plunge once again. They’ve been up and down with the business cycle since.

Jordan Weissmann

Why focus on the roller coaster of the 1970s, ‘80s, and early ‘90s? Because, according to the Census Bureau, that’s when the biggest shifts in American family structure took place, especially for white and black families.

If you reach up the income ladder, things look a little more placid, at least by Winship’s account. According to his favored measure (in green), median male earnings are up since 1979. But, as you can see, that result changes depending on precisely who is counted, and how you measure for the rising cost of living.

Scott Winship

The main point, regardless, is that by Winship’s own analysis, the past 40 years or so have been an incredibly rocky time for at least a quarter of non-Hispanic American males. And it was arguably rockiest at the moment in history when two-parent families were unwinding fastest.

This isn’t to say that the economy, and growing inequality, are the only reasons family structure has changed in this country. As I wrote earlier this week, our cultural mores regarding sex, marriage, and parenthood are almost certainly a causal factor as well. So is the war on drugs, which incarcerated so many fathers. The fact that female pay has been rising this whole time has almost certainly contributed as well; now that they can rely on their own income, women are probably a lot less willing to settle down with a not-so-great guy with a menial job than they were in 1973. In the end, it simply isn’t easy to separate all of this stuff. It’s all inter-related and has created feedback loops that probably did more to break down the ideal of the two-parent family than any one of these changes would have on its own.

But the claim that working-class men have been doing basically OK this whole time isn’t just counterintuitive; it’s simply not true. And you can’t simply write their troubles out of this story.