Arkansas: It’s for the kinds of lovers who sometimes need a mulligan on their relationships.

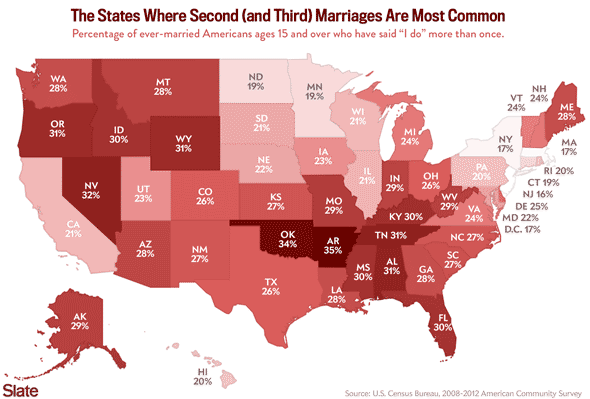

This week, U.S. Census Bureau researchers reported that, of Americans who have ever wedded, nearly a quarter had been married at least two separate times in their lives. But, as always, there were some stark differences state to state. In the Northeast, for instance, second and third marriages are relatively uncommon. In the South and West, on the other hand, people walk down the aisle both early and often. Nowhere is this more the case than in the Razorback State, where around 35 percent of ever-married adults have said “I do” more than once.

Click to enlarge. Vivian Seibo/Jordan Weissmann

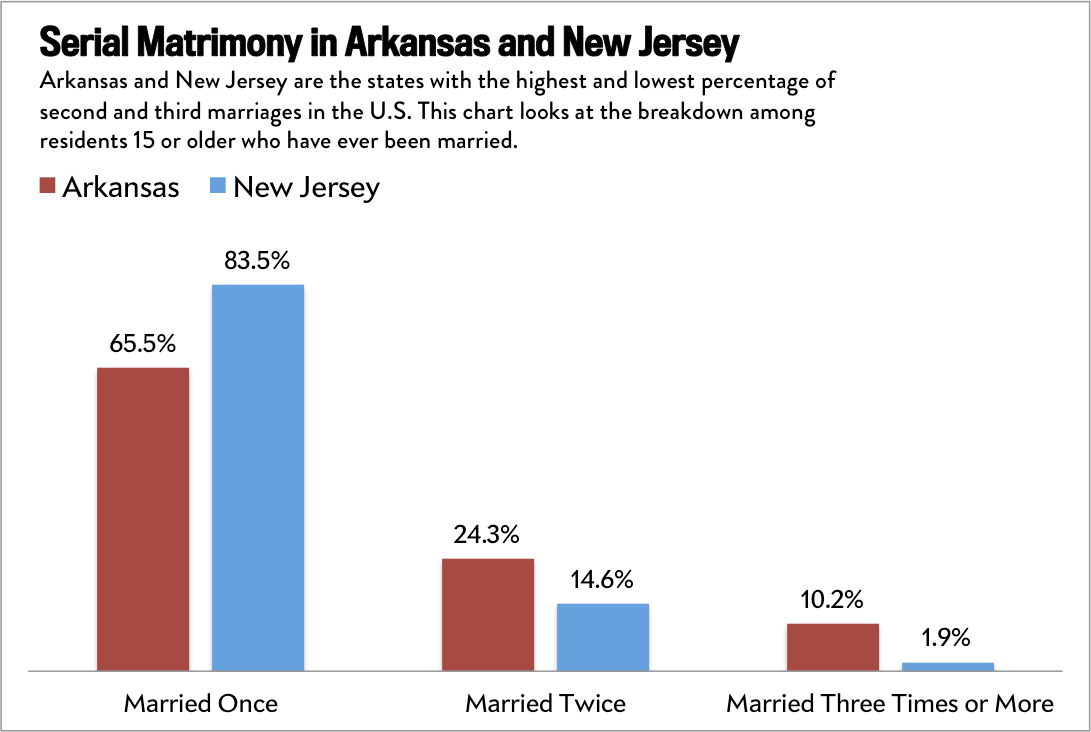

Arkansas also led the nation in third marriages. Of the state’s ever-married population, 1 in 10 had given matrimony at least three different shots. In New Jersey, the state with the fewest remarriages, not even 2 percent had made it to that many wedding days.

Jordan Weissmann

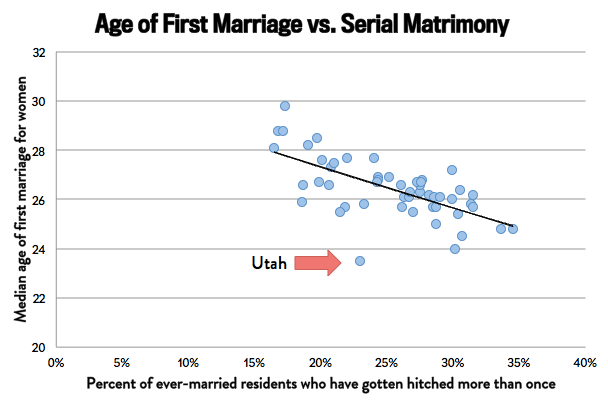

As you might suspect, the fraction of second and third marriages in a state has a fairly strong correlation with divorce rates. It also seems to mirror the rate at which people first get married: In the places where Americans get hitched young, there’s a pretty strong chance they’ll get hitched twice. (The one really notable outlier from that trend is Utah, which may have to do with its large, culturally conservative Mormon population.)

Jordan Weissmann

In a sense, then, remarriage rates are just another way of framing the familiar issue of instability in American families. It’s not especially shocking that in high-divorce, high-poverty states where people wed early, you’d see people marrying over and over. But the numbers do provide one useful illustration of and commentary on a concept that sociologist Andrew Cherlin calls “the marriage-go-round“—the idea that Americans are uniquely prone to cycling in and out of relationships, whether they’re just living together or married, and that the constant churning ultimately takes a toll on children. While that might be part of our romantic character nationally, the issue is far more severe in some corners of the country than others. In the Northeast, you might not hear as much preaching about family values. But people seem to live up to them relatively well.