Etsy, the artisanal online marketplace and standard-bearer of the “quaint economy” and burgeoning Brooklyn startup scene, did a very unquaint thing on Wednesday: It applied to be listed on the Nasdaq Stock Market in an initial public offering that, according to preliminary documents, could raise as much as $100 million.

Etsy, which values itself at about $1.7 billion, has yet to turn a profit. In 2014, it recorded a net loss of $15.2 million, according to its prospectus. The two years before that, it lost $796,000 and $2.4 million. At the same time, its revenues have grown substantially. In 2012, Etsy said it produced $74.6 million from its marketplace, seller services, and “other” things; in 2013 that figure climbed to $125 million and in 2014 it reached nearly $200 million.

Where is all this revenue coming from? Etsy says it had 1.4 million active sellers and 19.8 million active buyers as of Dec. 31, 2014, and that year the average seller on it platform contributed $1,400 of revenue. That said, it also defines these things rather loosely. An active buyer is someone who had made “at least one purchase in the last 12 months”; an active seller “has incurred at least one charge from us in the last 12 months.” Etsy makes money by charging 20 cents to sellers for each product listed on its platform and taking a 3.5 percent cut of each transaction.

Etsy

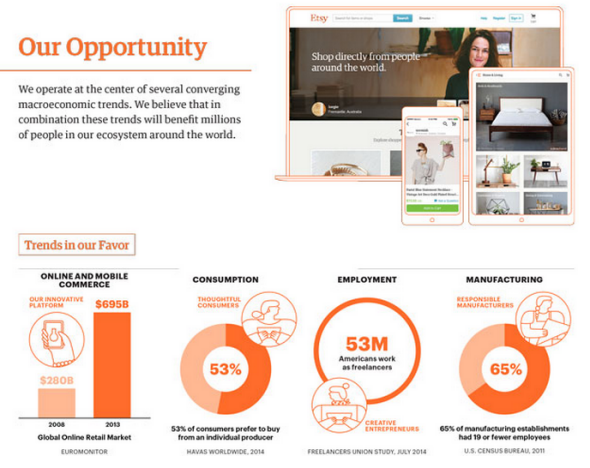

With its IPO plans, Etsy sees itself capitalizing on several promising economic trends, or what is best summed up as the quaint economy (TQE). These include increased consumer interest in local or handmade products, a trend toward freelance work, and of course a ballooning market for mobile and online shopping. Etsy notes in its prospectus that failing to maintain the image of an “authentic, trusted marketplace” that values “unique offerings” and “handmade goods” could be a risk to its business.

And yet, sellers on Etsy’s platform are among the first to admit that the company long ago departed from its authentic and handmade roots. In late 2013, Etsy changed its policies to allow sellers to partner with outside manufacturers to produce their goods. The shift angered many of Etsy’s earliest users, but some still found it hard to leave because of the company’s huge customer base. “I think Etsy has already lost some of its quaintness, but as long as buyers can differentiate between the genuine handmade goods and the imported impostors, then it’s OK,” Rachel Pfeffer, a jeweler on Etsy, wrote me in an email.

It’s anyone’s guess whether Etsy will be able to hold onto what’s left of its image as it goes public. The important point would seem to be that to succeed it might not have to, despite what the risk factors say. The inherent irony in the quaint economy, after all, is that so much of “quaint” is tied up in keeping things small, and so much of “economy” is about scaling up to just the opposite. There’s nothing quaint about an IPO being led by Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and Allen & Company. And similarly, there’s nothing quaint about a $1.7 billion valuation, no matter how many ceramic water-lily coasters are behind it.