It’s been a decent couple of weeks for America’s underpaid retail workers. First, Walmart announced it was raising wages for 500,000 of its associates—up to a minimum of $9 an hour this spring, and $10 next year—in a bid to increase morale and performance. Wednesday, TJX, the owner of clothing discounters T.J. Maxx and Marshalls, said that it was following suit. Target is still holding out, but companies are obviously feeling some pressure to up their remuneration for the people who make their stores run.

Why now? There are lots of little reasons, to start. States are hiking their minimum wages—in all-important California, the floor will be $10 in 2016—meaning that these companies would have faced higher payroll costs regardless. Meanwhile, Walmart is trying to combat its toxic public image as the king of low-wage employment, which hasn’t been helped by the steady protests organized by the worker group OUR Walmart. At the same time, its labor practices, designed to ruthlessly minimize expenses, have become a major business liability in recent years, as badly understaffed supercenters haven’t been able to keep merchandise stocked on shelves, leaving it to stack up in storage while customers head elsewhere. The company’s new chief executive, Doug McMillon, thinks that improving customer service is key to turning around its performance and is betting higher pay will lead to happier, more productive staff (and the best research suggests he’s right).* And if Walmart is offering higher wages, its competitors will probably need to do the same to compete.

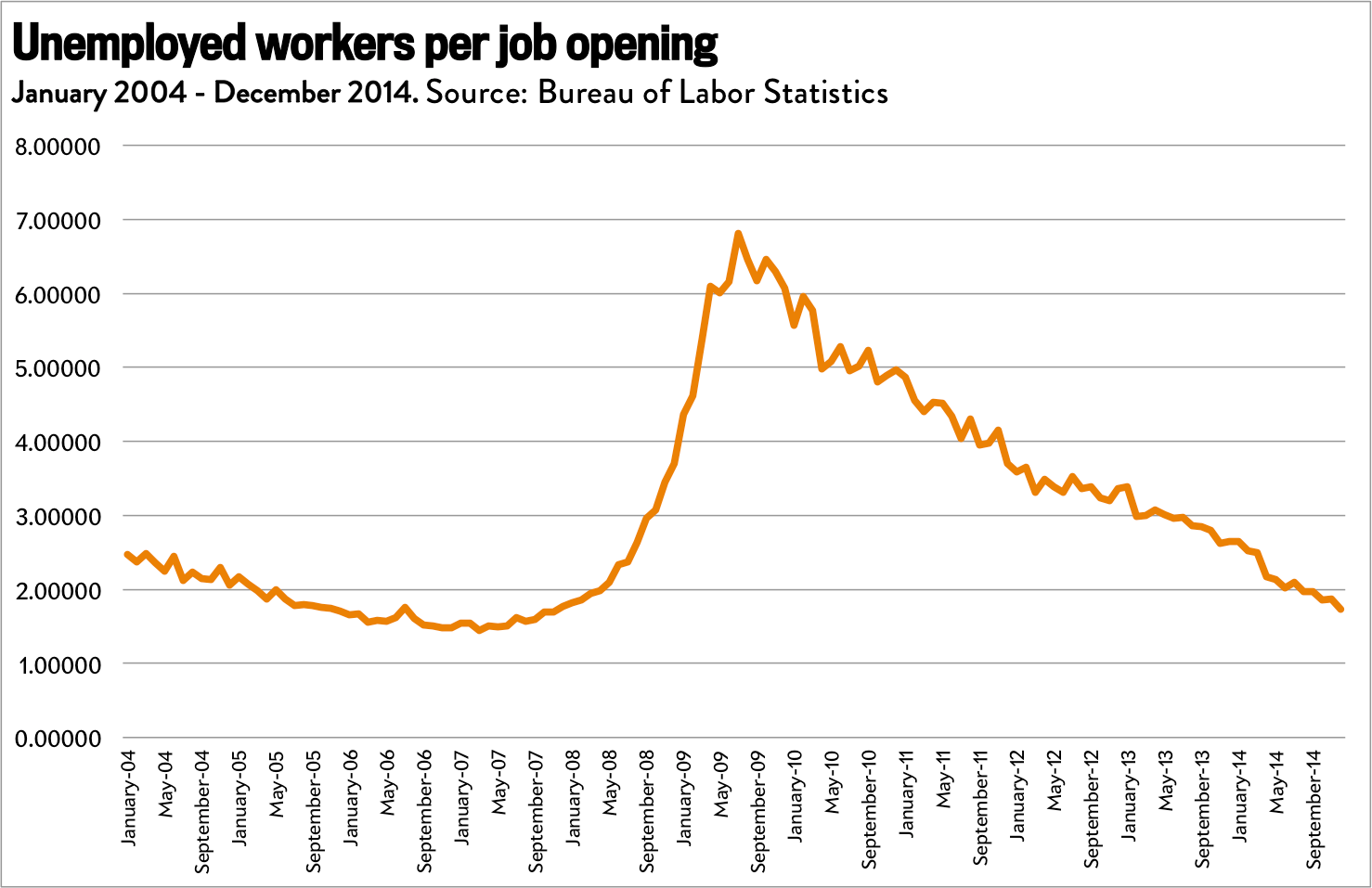

But that brings us to the big issue. The job market isn’t just healing. It’s now getting somewhere close to normal again. There are about 1.7 unemployed workers per job opening now, close to the lows of early 2007. That line you’re looking at? The lower it falls, the more impetus companies will have to raise their compensation, since employees will feel more comfortable quitting to go looking for a higher paycheck elsewhere. And indeed, as Matt Yglesias notes today, more and more Americans have been saying “so long” to their bosses lately.

Jordan Weissmann

There is one potential sour note here. Since the recession, many Americans have simply given up on finding work after facing grueling stretches of unemployment. One reason the job market looks like it’s getting tight now is that many of those people are sitting on the sidelines, and it’s unclear if the recent good news will bring them back. The labor force participation rate for workers between the ages of 25 and 54—basically, people who are too young to be retiring—has ticked up slightly in recent months after a period of decline followed by stagnation. But it’s too early to tell if that’s a blip or the beginning of a sustained trend.

We want those missing workers to return to job market. If they do, that should help alleviate the need for companies to increase wages. If they don’t, well, at least a few more Americans should be in for a raise.

*Correction, Feb. 26, 2015: This post originally misspelled Walmart CEO Doug McMillon’s last name.