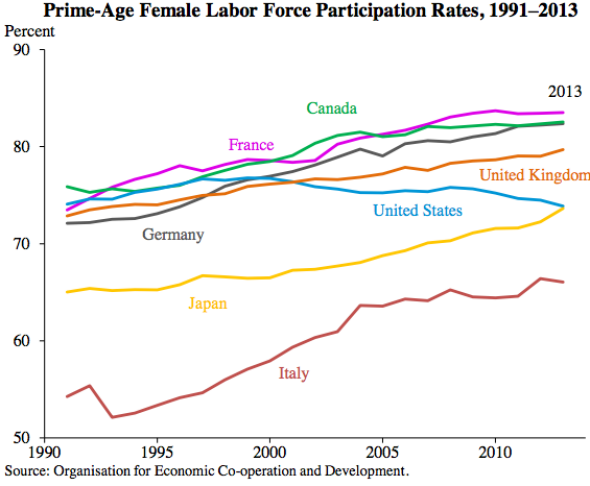

By global standards, the United States used to be a great country for working women. But these days, we look hopelessly behind the times. As the White House noted in a recent economic report, American women between the ages of 25 and 54, which are considered an adult’s prime career years, are now less likely to be employed or on the job market than women in much of the developed world. On that score, we’re closer to Japan, a country still trying to overcome its history of hostility toward women in the workplace, than we are to Canada or Europe.

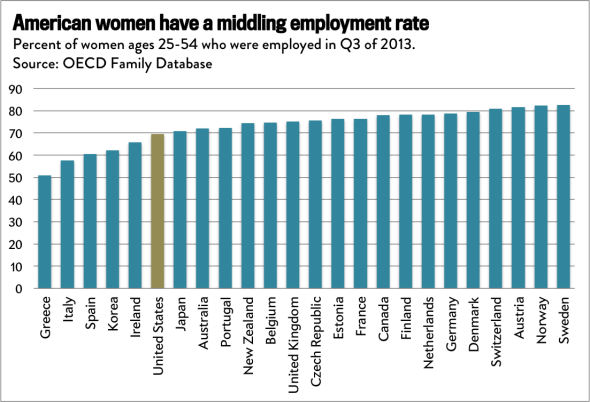

The picture doesn’t improve much if you broaden it out. According to the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development, there were at least 18 rich countries where prime-age women were more likely to be employed than the United States in 2013, the last year with data. Aside from South Korea, which has a strong patriarchal culture, we were faring better than Greece, Italy, Spain, and Ireland—countries that were still digging their way out of economic crisis.

Jordan Weissmann

The reason for all of this isn’t much of a mystery: It’s our pitifully stingy public policy toward women and families. We are one of three countries in the world, along with Papua New Guinea and Oman, that doesn’t guarantee paid leave for new mothers. We also offer few protections for part-time workers, which makes it harder for women to keep a foot in the workforce after children. A study by economists Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn of Cornell University found that, if U.S. family policy looked more like Europe’s, employment among U.S. women would have been 7.2 percentage points higher in 2010.

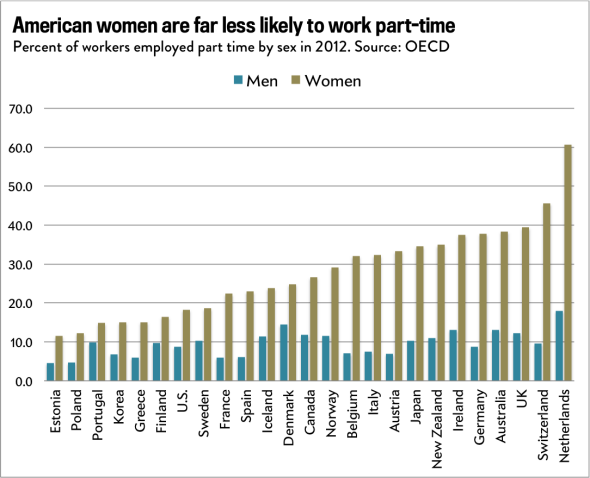

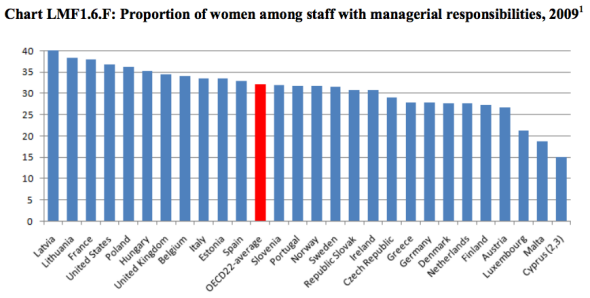

Europe does have its own struggles with this issue. While women there are more likely to stay in the workforce, Blau and Kahn find that the long leaves and flexible schedules guaranteed to them by law encourage them to work part time. That can stunt their careers, preventing them from moving into management. The U.S., in contrast, has relatively low rates of part-time work among women. (As an aside, that’s also why, even though our labor force participation rate for women is on par with Japan’s, it’s misleading to suggest, as some have, that our problem with working women is as bad as theirs.)

Jordan Weissmann

That said, some countries clearly get the balance right. One of the best examples may be France. France has a higher rate of part-time work than the U.S. (22 percent versus 18 percent). But because more females work overall, a similar percentage of all women are employed full time there as they are here. It also has a somewhat smaller gender wage gap than the U.S., as well as European neighbors like Germany or even famously egalitarian Sweden. And, perhaps most tellingly, women make up a higher percentage of managers in France than just about any other truly rich nation tracked by the OECD. It’s clearly possible to offer women bountiful social support without sidetracking them from their careers. They’re also near the top for the percentage of women on corporate boards (though they trail far behind Norway, which has a legal quota for females on board seats). And should you be wondering, French women manage all this while having more children than American women.

A generous family policy can be a bit of a double-edged sword, capable of keeping women in the workforce, but out of top jobs. But as France shows, it’s possible to hit the balance correctly. We could certainly stand to take a few of their lessons.