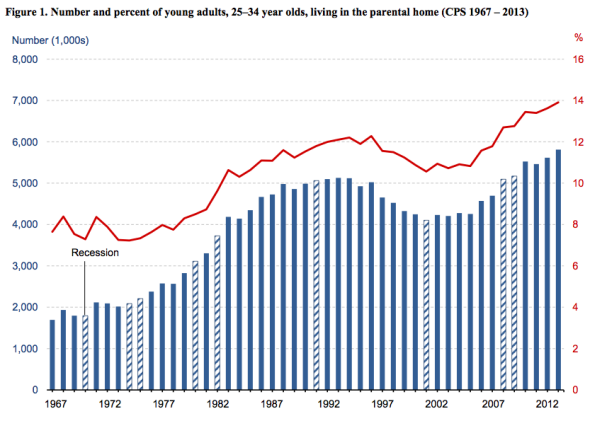

Last year, even as the job market picked up speed, the fraction of 25-to-34-year-old Americans living with their parents stayed stuck at record highs nearing 15 percent, according to the Census Bureau. Seems odd, right? After all, millennials have been moving home in historic droves mostly because of the weak economy, haven’t they?

Maybe not. In the past several months, a handful of studies have suggested that the reasons grown children are returning to the nest in greater numbers than ever may have less to do with the rise and fall of the unemployment rate, and more to do with lasting changes to young adult life, such as the growth of student debt and delayed marriage.

To put it another way, when it comes to twenty- and thirtysomethings living with Mom and Dad, it’s possible we’re looking at something close to a new normal.

In September, a working paper by Federal Reserve board economists Lisa Dettling and Joanne Hsu found that rising student debt levels could explain about 30 percent of the increased rate at which young adults, ages 18 to 31, began moving in with their parents between 2005 and 2013. Local unemployment rates had a far smaller effect. And once falling housing prices were taken into account, the authors concluded that economic conditions should have actually decreased the number of boomerang kids (after all, even if jobs are hard to come by, cheaper real estate makes it easier to live solo). But debt was driving adults back into their childhood bedrooms.

Those findings were largely echoed in a November staff report by researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Home prices and rising unemployment rates “may have increased parental coresidence,” the authors wrote, but “student debt could play an even larger role in keeping young people at home, possibly explaining as much as 50% of the increase since 2003.” In general, they found that in states where college graduates finished school with more debt on average, young adults were more likely to live with their folks.

The Federal Reserve studies share at least one minor shortcoming. Both rely on credit report data, which identifies individuals based on their address, but doesn’t explicitly reveal whether people who live together are actually related to one another. To make up for this, the papers work from the assumption that young adults live with their parents if they share a home with a significantly older adult. It’s possible, therefore, that a 26-year-old renting a couple’s basement in Washington, D.C., while working on Capitol Hill would be incorrectly treated as a boomerang kid in their analysis. So would a 23-year-old who, thanks to whatever odd quirk of Craigslist fate, shares an apartment with a 45-year-old roommate. But in both studies, the authors argue that census data suggest those situations are fairly rare.

Still, there are some obvious reasons to be skeptical about both Federal Reserve studies. First, it seems possible that looking at home prices may have underestimated the role of real estate, since median rents actually rose through part of the recession. Beyond that, living-at-home rates grew faster during the recession for young adults who never attended college than those who did. Presumably, most of them didn’t have any education debt, and something else was at play.

On the other hand, neither study suggests that student loans, or economic factors, explain the entire migration of millennials back home. So what else might play a role? One answer could be marriage. An analysis by the U.S. Census Bureau’s Jonathan Vespa and Laryssa Mykyta found that the growing proportion of never-wedded 25-to-34-year-olds could entirely explain why more of those young adults moved in with their parents during the Great Recession than in past downturns.* The unemployment rate, in contrast, didn’t seem to make a difference (which makes sense when you consider that relatively fewer young adults boomeranged during the 1980s double-dip recession, even though joblessness peaked higher).

“The relatively earlier ages at marriage during the 1970s and 1980s acted as a brake on living with parents during that period,” they wrote, “whereas later ages at marriage in the 2000s accelerated the share of young adults living with parents.”

Like the Federal Reserve studies, Vespa and Mykyta’s paper needs a few caveats. To start, it doesn’t factor student loans into its analysis, which seems like an obvious blind spot. Second, it compares recessions to other recessions; implicitly, it still suggests that the percentage of young adults living at home will eventually fall a bit when as unemployment continues to fall.

But the decline of young marriage is an appealingly straightforward explanation for some of the trends we’ve seen in the past several years. It’s easier for a couple to pay rent on an apartment than someone who’s single. When they run into financial trouble, spouses can rely on each other for support (and, you know, not many of us want to move in with our in-laws). But beyond that, marriage rates have declined most among Americans who never went to college, that same group among whom living with parents is commonest and has grown fastest.

So, what are the takeaways? In the end, all three of these analyses are still very preliminary. But let’s say they’re directionally correct, and debt and postponed marriage are really the dominant forces driving young adults home rather than unemployment. One conclusion might be that young adults are simply more susceptible to a bad economy, or plain old career trouble, than they used to be. It’s not high unemployment, per se, that’s a problem so much as the fact that we’re less prepared to deal with it, thanks to the fall of marriage and the rise of debt. And what about when the job market finally gets back to full health? We should probably still expect more young people to live at home than in the past. Student loans aren’t disappearing any time soon. Americans aren’t getting hitched any earlier. Parents might want to think about keeping that extra bed around, just in case.

*Correction, Feb. 10, 2015: This post originally misspelled the first name of Laryssa Mykyta.