Writing a recipe for startup success is like trying to bottle lightning. Estimates, after all, put the startup failure rate as high as 90 percent; there’s a reason “fail fast, fail often” is a Silicon Valley mantra. Several years ago, a study of venture-backed firms by researchers at Harvard University found that entrepreneurs who have succeeded once are more likely than first-timers to succeed in the future, but that still just scratched the surface of what works for company founders and why.

Last week, a new study published in Science, “Where Is Silicon Valley?,” attempted to come a little closer to identifying what separates the startups that make it from the ones that don’t. The researchers’ findings: Startups that are more likely to succeed have short names, are not named after their founders, and are located in regions associated with “high quality” ventures. In particular, the authors write that eponymous firms are more than 70 percent less likely to succeed than others while firms with short names (defined in their paper as three or fewer words) are 50 percent more likely to succeed than those with long names. Menlo Park, Mountain View, and Palo Alto are the top-rated cities for so-called entrepreneurial quality. Successful firms were considered ones that achieved an initial public offering or an acquisition within six years of being founded.

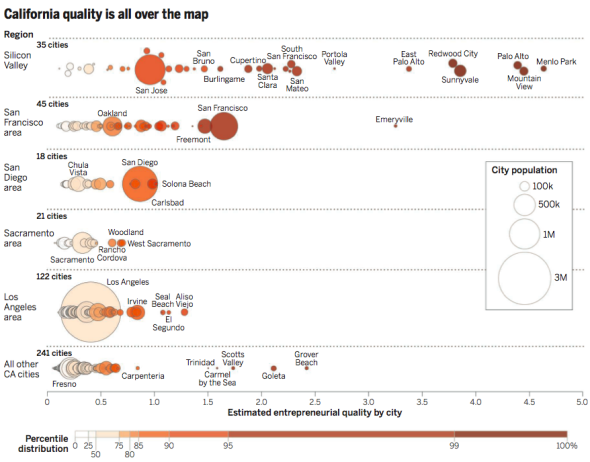

To conduct their study, the authors looked at data on for-profit business registrations in California between 2001 and 2011, as well as data from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and Thomson Reuters. After rating the firms for their entrepreneurial quality, the researchers estimated the average quality of firms in each California city and ZIP code. The records they used in the process were important because they let the authors look at companies right from their founding—before venture capital had been invested or anything else. So when Menlo Park and Mountain View and Palo Alto emerged as the best cities for entrepreneurial quality, it wasn’t necessarily because the companies in that area had more funding off the bat that allowed them to set up shop there.

From “Where Is Silicon Valley?”

“What we’ve been able to do here is move one step back and sort of get the raw material at inception rather than the impact of venture capital,” Scott Stern, one of the study’s authors and a professor of management at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told me. “We’re trying to measure things that companies do naturally when they have the ambition and potential to grow.”

That startups with shorter names tend to perform better is consistent with other research on naming. In 2013, a report from career site TheLadders found that shorter first names were correlated with higher annual salaries. With companies, particularly in tech, there has been a tendency to form names by misspelling common words, dropping vowels, or appendly “ly” (think: Flickr, Feedly, Pinterest, and so on). While the study in Science only examined name length in terms of number of words, Stern says the principles of eliminating letters are probably the same. “Firms are looking for names that are easy to remember, that will come up in a search,” he says. “If you have a smaller number of letters and you’re missing a vowel, you will have that distinctive search pattern.”

Of course, all this isn’t to say that startups will succeed just because they launch in the best-ranked areas for entrepreneurship and come up with short names. Rather, it’s that ambitious startups with ambitious founders tend to do the things that the ultimately successful companies do. “Our indicators are the digital trail of ambitious, high-potential entrepreneurs,” Stern says. “Simply having those digital trail markers is not enough—what needs to be true is the founders need to have ambition and potential so that those choices make sense in their overall business plan.”

That said, anyone narrowing down a list of possible monikers for their new venture might want to pre-emptively strike any long or eponymous name ideas from their list. It can’t hurt.