Back in November, two economists released a draft paper arguing that the abundance of cheap online porn had made American men less likely to get or stay married by providing a ready substitute for sex. Or, as they put it, “We assert that increasing ease of accessing pornography is an important factor underlying the decline in marriage formation and stability.” Now, this study is the subject a credulous write-up in the Washington Post that’s being widely shared and parroted on other sites, because, you know. Pornography. Tearing our society apart. Or something.

To be blunt, this paper is deeply silly. Mostly, it’s a good illustration of why, even when economists break out lots of math to show that correlation equals causation, it’s good to be skeptical.

Here’s how the authors—West Chester University of Pennsylvania’s Michael Malcolm and George Naufal of Timberlake Associates—went about their project.* Using data from the General Social Survey, they found that, adjusting for personal traits like education and income, men between the ages of 18 and 35 were less likely to be married if they admitted to visiting porn sites or spent lots of time on the Internet. (They tested the effect of overall Internet usage because they figured some men would lie about their porn habits.)

So they had correlation covered. But causation? This, they acknowledged, was trickier to prove. After all, one could easily conclude that many men enjoy porn because they’re single, not that they’re single because they enjoy porn. So, in order to show that the ability to stare at naked people on the Internet actually discouraged America’s young gentlemen from tying the knot, Malcolm and Naufal decided to use a statistical technique known as an “instrumental variable” test. Here’s where things get the tiniest bit technical, but it’s important.

In principle, instrumental variables are a neat tool researchers can use to show, or at least suggest, causation when they can’t run a true randomized experiment. Here’s a classic example. Let’s say you wanted to test the effect of cigarettes on public health, and your data tells you that people who smoke tend to be sicker than the rest of the population. Unfortunately, that still wouldn’t prove cause and effect, because there are lots of reasons cigarette users might just happen to be unwell (for instance, smokers are often less educated, so they may just make lots of poor health decisions that have nothing to do with inhaling nicotine). To build a stronger case, you could also test an instrumental variable—something that could only affect public health by changing cigarette consumption. One example would be tobacco taxes. The sole way increasing the price on cigarettes can realistically change public health is by lowering the smoking rate. If raising taxes on Camels correlates with less disease in a community, it’s a pretty sure sign that cigarettes do in fact make people sick.

The key thing about instrumental variables is that they can only affect the final outcome you’re studying (like the probability a man will get married) through the specific channel you’re testing (like his predilection for porn). If your “instrument” can influence the outcome through other means, then it’s pretty useless.

And that brings us to the first big problem with this porn paper. To test causation, the authors picked two instruments. The first was the subject’s father’s level of education, which meant to show if time spent on the Internet affected men’s chances of getting married. The second instrument was whether they lived an urban area, which was supposedly meant to show if porn use itself influenced marriage. The authors reasoned that the sons of educated fathers would be exposed to more technology as children, so they would be more likely to use the Internet as adults. They figured that cities have better online infrastructure, so urbanites would be more likely to use porn.

Does that reasoning sound strange to you? It is. The problem is that there are lots and lots of other ways, aside from Internet or porn usage, that having an educated dad or living in a city could change your propensity to get married. People who live in major metro areas have lots of dating options and might not want to settle down. College-educated parents often teach kids to put their careers before their love lives. Malcolm and Naufal basically admit all of this in their paper. But, then they plead for leniency, writing: “Nevertheless, better instruments are not available in the dataset.” In other words, “Well, it’s all we got.”

But what they’ve got is meaningless, because, again, the instruments they chose could affect marriage rates in any number of manners. To their credit, the authors do hedge a bit. “Limitations of the dataset do not allow us to conclusively state that we have identified the true causal effect, but we will argue … that our results suggest such an effect,” they write. But that’s still arguing too much.

There are other problems with Malcolm and Naufal’s paper. The pair also shows causation by noting that porn users and nonusers are largely similar in ways captured by the General Social Survey, which is a regular poll that has asked Americans about their backgrounds, lifestyles, and beliefs since 1972. But that may just mean the survey fails to capture a lot of relevant information about its participants. Meanwhile, the GSS doesn’t track its participants over time, so many of these men who allegedly choose porn over wedded bliss may indeed get married later. And, as has been well-established, people who get married older are less likely to get divorced. Delayed marriage isn’t a bad thing.

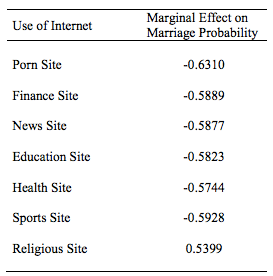

Or try this odd discovery. Yes, Malcolm and Naufal find that men who visit porn sites are less likely to be married. But, according to their research, so are men who visit sports sites, finance sites, news sites, or education sites. The only exception? Religion sites.

So in conclusion, this paper seems to suggest that men who look at porn avoid the trap of early marriage—but for reasons that cannot be discerned from its statistical approach—and that reading sites like Yahoo! Finance, among others, is associated with a lower chance of having found a spouse. But writing that wouldn’t be quite so sexy, now would it?

*Correction, Dec. 23, 2014: Due to a typo, this post originally misspelled Michael Malcolm’s first name as “Micahel.”