How ‘bout them oil prices, huh? Crude continued its long slide today, with the U.S. benchmark price dipping below $60 a barrel for the first time since July 2009, when the country was just fresh off the recession. The cause? Well, OPEC cut its estimate for how much oil the world will need next year, and Saudi Arabia, the cartel’s most powerful member, reiterated that it had absolutely zero plans to cut production, which would theoretically take some of those excess fossil fuels off the market and push prices back up.

“Why should I cut production?” Ali al-Naimi, the Saudi oil minister, told reporters yesterday. “This is a market and I’m selling in a market. Why should I cut?”

Nami’s quip is more than a delightfully dismissive retort to the question on the mind of just about every global oil executive (who would all surely love it if the Saudis cut back, you know, just a bit). It’s also a nice reminder that some countries stand to suffer a lot more in this oil market route than others—and the Saudis, by most standards, have just about nothing to fear. So, I thought this would be a good moment for quick review of the winners and losers.

There are at least three numbers that you have to remember when we talk about whether falling oil prices are a problem for a country:

- The fiscal breakeven: The oil price necessary for a government to avoid running a budget deficit.

- The accounting breakeven (or what most people just call the “breakeven”): The oil price necessary for an oil drilling project to be profitable

- The cash cost: The oil price necessary for drillers to keep their pre-existing projects operating.

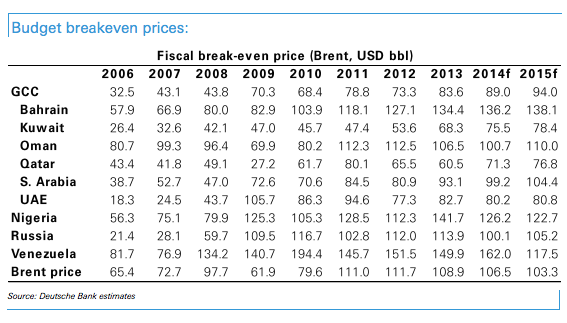

First stop: fiscal math. For countries like the United States that don’t generate a great deal of tax revenue from oil production, falling prices are generally good economic news, since cheaper fuel puts more money in consumer profits. But for the oil dependent nations of OPEC, cheap crude is a budget nightmare. And, as Deutsche Bank pointed out in an October analysis, oil producers like Russia, Venezuela, and Nigeria all need prices above $100 a book to balance their books. Even Saudi Arabia needs around $99 to support its spending.

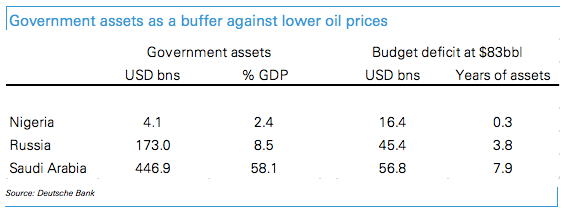

But deficits are a bigger problem for some countries than others. Thanks to their massive dollar reserves, the Saudis can afford to overspend for a while. Russia, too, has a little bit of a cushion. Countries like Nigeria that barely have any reserves are in far greater trouble.

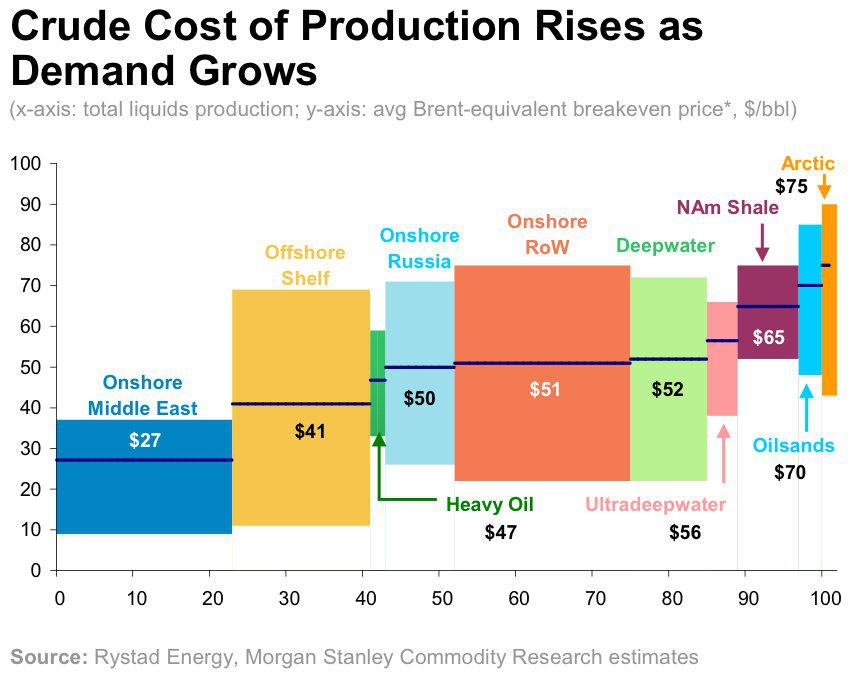

Now let’s forget government for a while. What about the basic price necessary just to keep oil projects profitable? That number varies enormously across the globe, and it incorporates expenses including the cost of oil exploration, building rigs, drilling, daily production, and marketing, among other bits. It’s much more costly to go hunt for oil in the frozen arctic deep, or to use techniques like fracking and horizontal drilling to extract oil out of U.S. shale deposits, than it its to pump conventional oil straight out of the Arabian desert. As this graph from Morgan Stanley (posted by Business Insider) nicely illustrates, the Middle East indeed has the lowest breakeven prices—generally falling well beneath the $40-a-barrel mark. The number can be far higher in other parts of the world, such as Russia, or in America’s shale basins.

Morgan Stanley

The breakeven price is especially important in the United States, because the unconventional wells that have fueled our domestic oil boom deplete quickly, meaning that companies need to keep drilling new ones to keep production up. If it’s suddenly not profitable to do so, then we should expect the flow of crude to taper off (as I wrote last week, that wouldn’t necessarily be a bad thing). This is one reason that many analysts think, rightly or wrongly, that the Saudis are essentially waging a war of attrition to drive down U.S. production and preserve their market share.

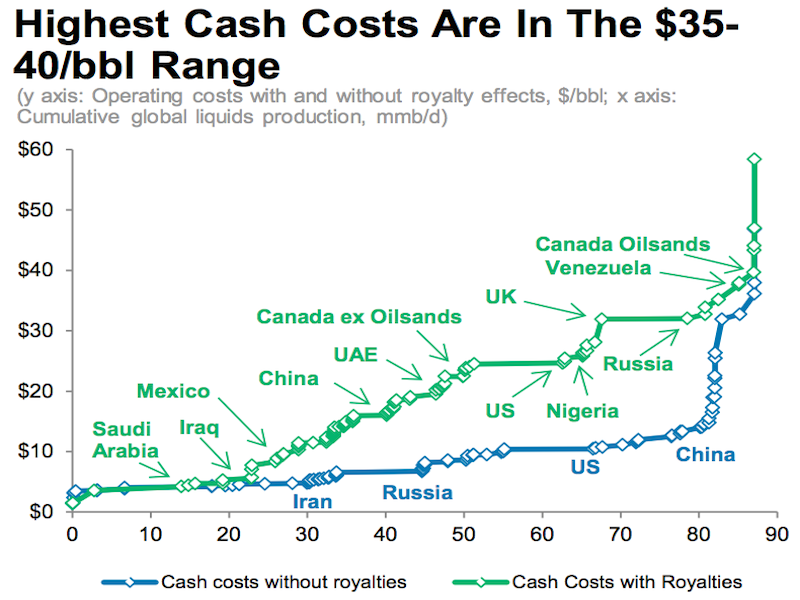

But even if a pre-existing well stops being profitable based on the cost it took to find and drill, that doesn’t mean Exxon or Shell will suddenly shut it down. No, the price to keep your eye on at which oil companies will suddenly start pulling the plug on projects that are already operating is known as the “cash cost”—the bare amount of money necessary to cover daily production, taxes, and marketing. And that figure can be quite low, as shown in this graph from Morgan Stanley. The green tracks the cost including royalties paid to the government, whereas the blue is raw production expense.

Morgan Stanley

The cash cost for most oil is still far below the $50 a barrel mark. But again, Saudi Arabia has some of the lowest costs of all. In some countries, including Venezuela, the magic price for keeping the lights on is in the $35-to-$40-per-barrel range. And some market watchers think its conceivable oil will indeed fall that low. So, why should Saudi Arabia cut production? Only if it wants to make sure Venezuela doesn’t implode, I suppose. But in pretty much any scenario, the Kingdom will be just fine.