Pretty much the entire academic-industrial complex has an interest in convincing high school students that it’s really, really hard to get into a good college. Universities love to brag about their low acceptance rates, which help them scale the rankings. Test-prep companies and admissions consultants play up the competitiveness of the admissions race to justify their fees. And so we get a regular diet of articles about how it’s harder than ever for kids to win that ticket to the school of their dreams.

That might be the case for an 18-year-old who has eyes only for Yale. But as the New America Foundation’s Kevin Carey argued in the New York Times this weekend, it’s much easier to get into a great college than the panicked stories about collapsing acceptance rates would suggest. How easy? According to Carey, “80 percent of top students were accepted to at least one elite school” this year.

When writers rant and rave about how hard it is to get into college these days, they tend to focus on how schools like Harvard and Stanford now accept fewer than 6 percent of applicants, or how former safety schools have suddenly become competitive. But, as Carey and others have pointed out, looking at admissions rates for individual institutions is misleading if you’re interested in figuring out the odds of getting into a good college in general. That’s because high school students, ever fearful of rejection, and assisted by the common app, are applying to more colleges than in the past. That’s driven acceptance numbers down. Beyond that, many of the kids taking a shot at the University of Chicago or Wesleyan or the University of Michigan simply aren’t qualified, so they aren’t really making the process any more competitive than in the past for students with high grades and SATs.

When it studied the issue a few years back, the Center for Public Education found “it was no more difficult for most students to get into college in 2004 than it was in 1992.” In fact, for the smartest kids, it was slightly easier. Applicants in the top 10 percent of their high school classes had a 68 percent chance of getting into a “highly competitive” college, up from 61 percent 12 years earlier.

Those numbers, of course, are very different from Carey’s ever-so-comforting 80 percent figure. And like all sticky stats, his needs some explaining—and caveats. Its based on data from Parchment.com, which 800,000 students used to submit transcripts. The company looked at students with SAT scores above 1300 who applied to one of the 113 most selective schools in the country, according to Barron’s Profiles of American Colleges. The average admission rate for these schools was 32 percent. But the ace test-takers managed a 51 percent rate. And overall, eight out of 10 got into at least one of those 113 top institutions.

The first thing to realize about this method is that not every parent might consider the “elite” college in Parchment’s study particularly elite. Along with the likes of Columbia and Amherst, Barron’s top tier includes schools like the University of Rochester, University of Richmond, the Webb Institute (a small engineering college), and the University of Miami. By most sane standards, these are very good colleges. But in the eyes of a hypercompetitive helicopter parent in a wealthy suburban school district (or, worse yet, one with kids at an expensive private school) they might not make the grade.

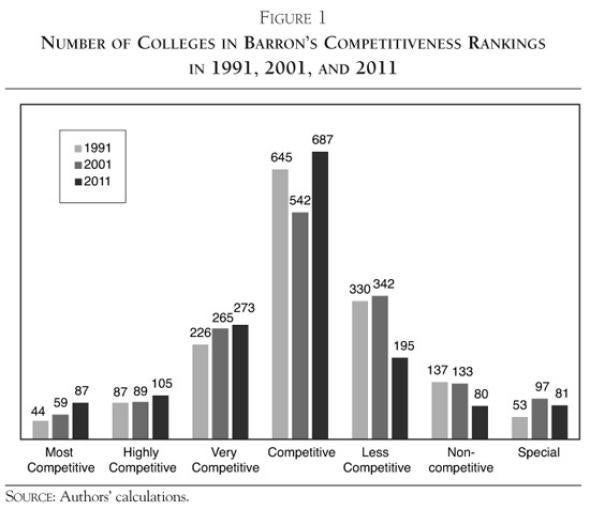

Second, according to Barron’s, there are a lot more competitive schools than there used to be. How come? Well, the guide bases its rankings partly on acceptance rates. And, as we’ve discussed, acceptance rates have fallen in part because students now apply to more schools. As this chart from the American Enterprise Institute shows, the number of colleges in Barron’s “most competitive” tier nearly doubled between 1991 and 2011. Academia may be suffering from a bit of “rankings” inflation, so if your notion of a top school is stuck in 1992, you may be a bit disappointed about where your kid ends up.

Finally, some elite schools are more exclusive than they used to be. First, while students have driven down acceptance rates by sending out a flurry of applications, the college-age population has also grown. Meanwhile, international students are now vying for more spots that might have once gone to Americans. Take Yale. In 1993, 4 percent of its class came from abroad. Now, it’s 10.5 percent.

So take Carey’s 80 percent figure with a bit of caution. But quibbles aside, he’s right about his big picture point: The college admissions race isn’t nearly so vicious as the people who profit from it would have you believe.