America’s nagging problem with college dropouts managed to get the tiniest bit worse this year. The National Student Clearinghouse reports that 55 percent of first-time undergraduates who matriculated in the fall of 2008 finished a degree within six years, versus 56.1 percent of those who began in fall 2007. Keep in mind, we already had the lowest college completion rate in the developed world, at least among the 18 countries tracked by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Much like American health care, American higher education continues to set a global standard for inefficiency.

Our dropout crisis doesn’t get discussed a great deal outside of education circles. But it should, since the issue is directly tied to other problems the public rightly obsesses over like rising tuition and student debt. Lots of Americans take at least a few college classes, which stretches state resources thin and drives up costs for everyone. But because relatively few finish their degrees, we get poor bang for our buck compared to other countries. And since dropouts are much more likely to default on their student loans, both borrowers and taxpayers end up suffering.

So it’s worth taking a close look at where and how the dropout problem is concentrated in the education system. Here’s the simple way to think about it: Traditional students—kids enrolled full time at four-year colleges by their 20th birthday—are very likely to finish school. Nontraditional students—pretty much everybody else—aren’t.

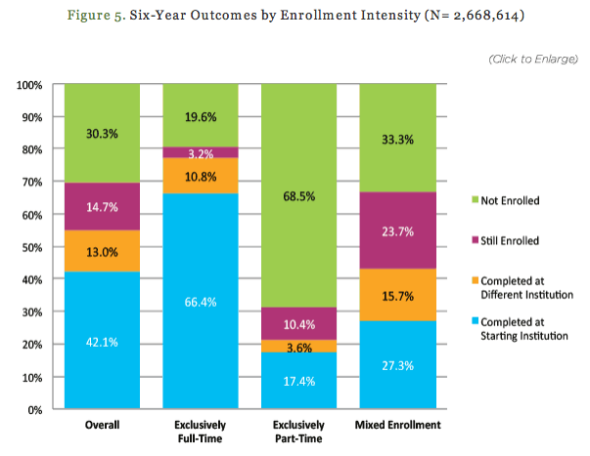

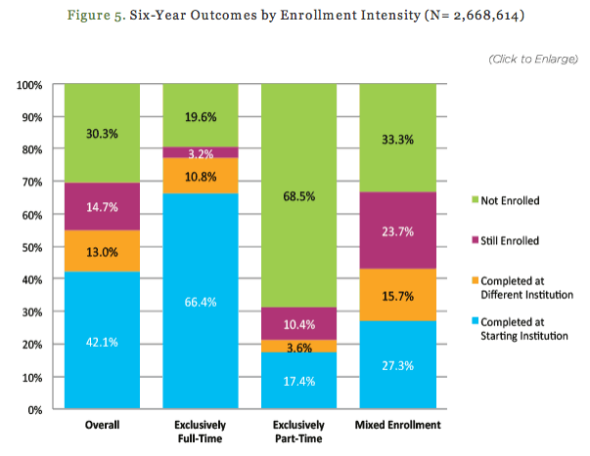

According to the NSC, only 39.6 percent of undergrads attended full time during their whole stint in school. They fared well: More than three-quarters of them finished up their degree within six years. On the other hand, the 53 percent of students who attended both full and part time struggled. One-third had dropped out entirely. Meanwhile, almost a quarter were still taking classes. Given that few students who spend more than six years in school finish, chances are most of them will drop out as well.

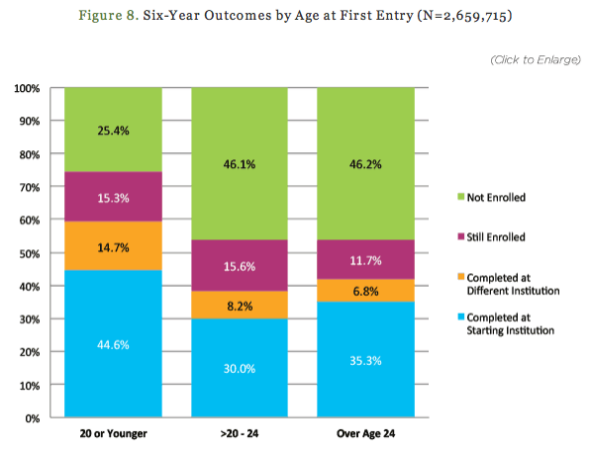

Now let’s take a look at age. Of those who started school at age 20 or younger—as 76 percent of 2008 enrollees did—about 59 percent complete a degree. For older students, graduation rates were closer to 40 percent.

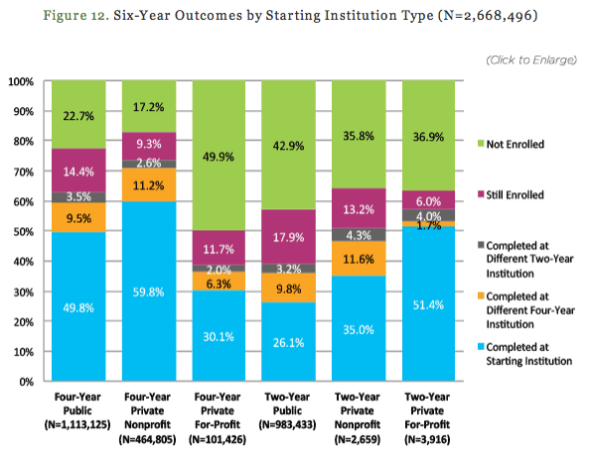

As you might expect, students at public and nonprofit four-year institutions—about 59 percent of the cohort—had far higher graduation rates than undergrads at two-year schools. A lot of this is self-selection: If you’re prepared to go seek a bachelor’s degree, chances are you’re better prepared to stick with higher ed. An enormous fraction of students at two-year schools aren’t prepared for college-level work and end up stuck in remedial classes, which lengthen the time to degree and make it less likely they’ll ever finish.

But even at four-year institutions, the distinction between full-time and part-time students still matters. Taking a few classes while working simply isn’t a very realistic path to a degree for most people.

Again, we have a higher education system that works fairly well for the traditional college student—the teenager who shows up on campus ready to dedicate the next four to six years of their lives to school. But a very, very large chunk of American undergraduates don’t fit that profile. They’re older, juggling classes and a job or family, and not necessarily up to speed academically. Our education system isn’t built to cater to their needs, and its results are extremely wasteful.