This month, Stanford University’s Pathways magazine gave new meaning to the phrase “third-world America” when it published an article reporting that, in any given month of 2011, 1.65 million U.S. households with children were living on less than $2 per person, per day—the sort of extreme poverty threshold usually associated with developing nations. According to H. Luke Shaefer of the University of Michigan and Kathryn Edin of Johns Hopkins, the number of families living under that low, low line has grown 159 percent since 1996. This, they argued, may have partly been the result of Bill Clinton’s welfare reforms, which made it harder for many families to receive cash assistance.

“The prevalence of extreme poverty in the United States may shock many,” the pair wrote. But is it really as prevalent as they suggest? A new report from the Brookings Institution argues: maybe not.

Part of the reason Shaefer and Edin’s headline number was so startlingly high—they calculated that the extreme poverty rate among households with children was a chilling 4.3 percent—could be attributed to a very narrow definition of income that ignored all noncash safety net benefits. Today, most of the government’s poverty-fighting efforts don’t involve straightforward cash. Food stamps? Housing vouchers? Tax credits? None were included. Once they accounted for those programs, only 613,000 families were living below the $2-a-day mark in 2011—still up by about half since the Clinton years.

At a bare minimum, then, hundreds of thousands of American households are living in true destitution. (For a family of three, the federal poverty line works out to about $17 per day, per person.)

According to the new Brookings report, however, even Shaefer and Edin’s most conservative estimates of extreme poverty might have been too high. If you look at data on income, the pair’s estimates essentially hold up. But Brookings fellow Laurence Chandy and MIT Ph.D. student Cory Smith found that if you examine U.S. consumption statistics, then the number of families surviving on less than $2 each per day falls close to zero.1

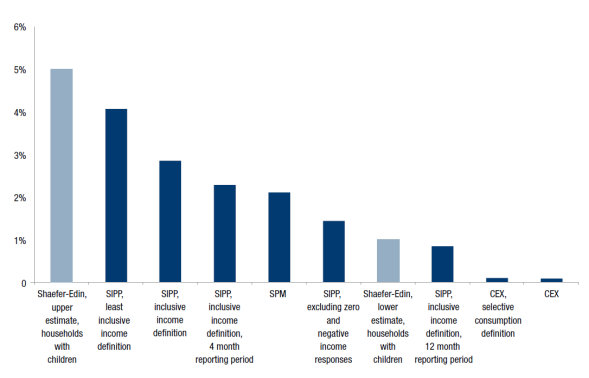

The Brookings chart below shows how estimates of extreme poverty can change, depending on your definitions and data source. Estimates based exclusively on cash income are on the far left; estimates including cash income and noncash government benefits are in the middle; and consumption-based estimates are on the far right.

Different Estimates of the $2 a Day Poverty Rate

America’s consumption data, which generally comes from the Department of Labor’s Survey of Consumer Expenditures, is notoriously shoddy. But critics generally complain about its failure to capture spending by wealthier households, which tend to underreport their personal budgets. Generally speaking, it’s thought to be a decent gauge of how middle-class and poorer families use their money.

So why does using consumption statistics lead to such drastically lower estimates of extreme poverty? It might be a data problem. It’s possible that the consumer surveys simply miss America’s poorest households, or that low-income families fail to report some of their income when asked. And even if the true extent of extreme poverty is ambiguous, the possibility that it exists at all should trouble us. “While the estimates we obtain vary,” Chandry and Smith write, “the fact that even some have millions of Americans living under $2 a day is alarming.”

1 Footnote: Interestingly, they also find that if you use the exact same methods researchers use to estimate developing world poverty, then the number of Americans living on $2 per day also falls to zero.