If you’ve ever found yourself fretting about the possibility that software and robotics are on the verge of thieving away all our jobs, renowned MIT labor economist David Autor is out with a new paper that might ease your nerves. Presented Friday at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s big annual conference in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, the paper argues that humanity still has two big points in its favor: People have “common sense,” and they’re “flexible.”

Neil Irwin already has a lovely writeup of the paper at the New York Times, but let’s run down the basics. There’s no question machines are getting smarter, and quickly acquiring the ability to perform work that once seemed uniquely human. Think self-driving cars that might one day threaten cabbies, or computer programs that can handle the basics of legal research.

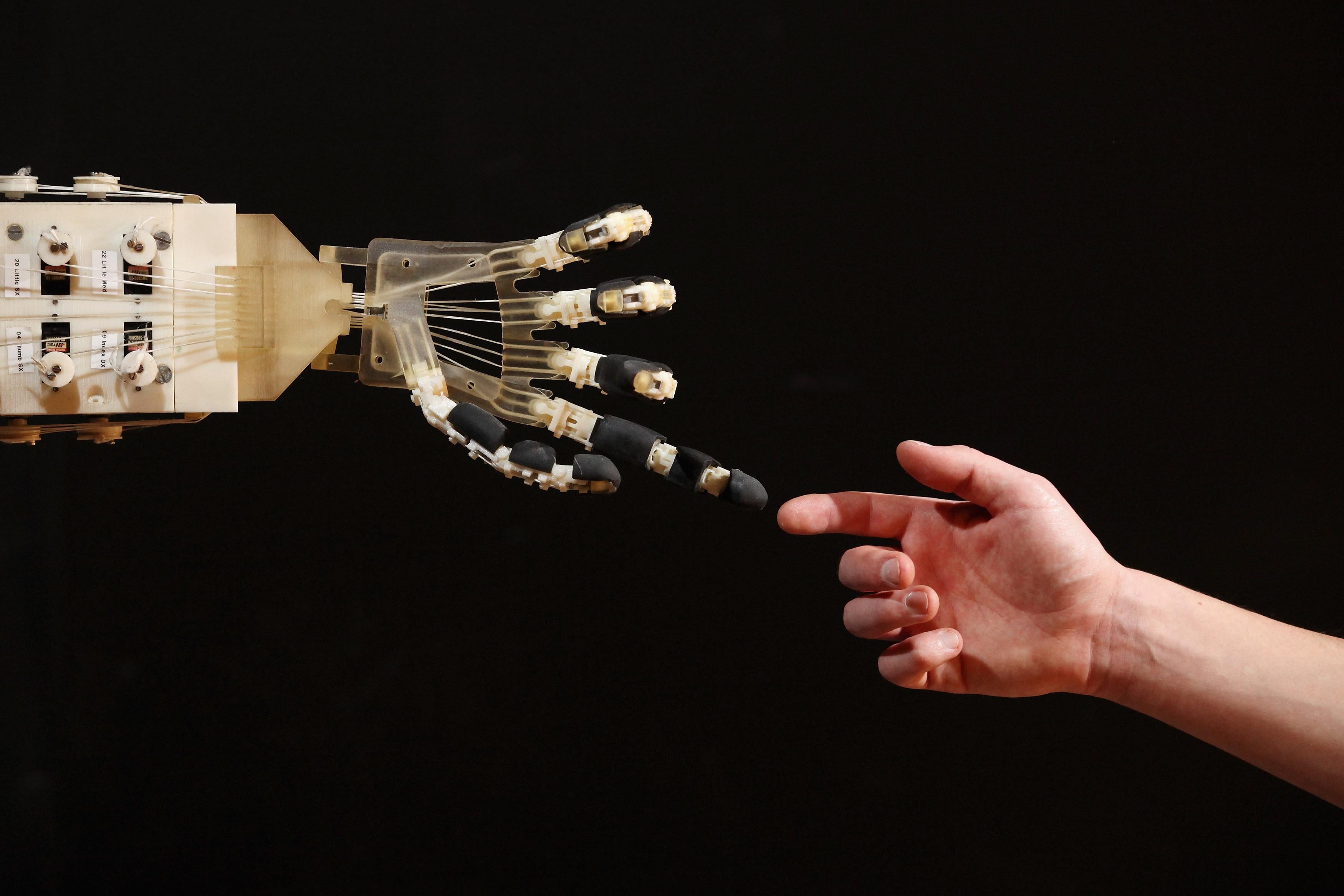

But artificial intelligence is still just that: artificial. We haven’t untangled all the mysteries of human judgment, and programmers definitely can’t translate the way we think entirely into code. Instead, scientists at the forefront of AI have found workarounds like machine-learning algorithms. As Autor points out, a computer might not have any abstract concept of a chair, but show it enough Ikea catalogs, and it can eventually suss out the physical properties statistically associated with a seat. Fortunately for you and me, this approach still has its limits.

For example, both a toilet and a traffic cone look somewhat like a chair, but a bit of reasoning about their shapes vis-à-vis the human anatomy suggests that a traffic cone is unlikely to make a comfortable seat. Drawing this inference, however, requires reasoning about what an object is “for” not simply what it looks like. Contemporary object recognition programs do not, for the most part, take this reasoning-based approach to identifying objects, likely because the task of developing and generalizing the approach to a large set of objects would be extremely challenging.

That’s what Autor means when he says machines lack for common sense. They don’t think. They just do math.

And that leaves lots of room for human workers in the future.

Technology has already whittled away at middle class jobs, from factory workers replaced by robotic arms to secretaries made redundant by Outlook, over the past few decades. But Autor argues that plenty of today’s middle-skill occupations, such as construction trades and medical technicians, will stick around, because “many of the tasks currently bundled into these jobs cannot readily be unbundled … without a substantial drop in quality.”

These aren’t jobs that require performing a single task over and over again but instead demand that employees handle some technical work while dealing with other human beings and improvising their way through unexpected problems. Machine learning algorithms can’t handle all of that. Human beings, Swiss army knives that we are, can. We’re flexible.

Just like the dystopian arguments that machines are about to replace a vast swath of the workforce, Autor’s paper is very much speculative. It’s worth highlighting, though, because it cuts through the silly sense of inevitability that sometimes clouds this subject. Predictions about the future of technology and the economy are made to be dashed. And while Noah Smith makes a good point that we might want to be prepared for mass, technology-driven unemployment even if there’s just a slim chance of it happening, there’s also no reason to take it for granted.