Jeff Smith, a New School professor and former Missouri state senator, had a sensational op-ed in this weekend’s New York Times that dived into the economic forces that have helped shape the strife in Ferguson. His big point is that the local police have a strong financial incentive to arrest, ticket, and otherwise harass the city’s black residents for minor offenses, because that’s how the department funds its budget.

How so? From Smith:

St. Louis County contains 90 municipalities, most with their own city hall and police force. Many rely on revenue generated from traffic tickets and related fines. According to a study by the St. Louis nonprofit Better Together, Ferguson receives nearly one-quarter of its revenue from court fees; for some surrounding towns it approaches 50 percent.

Municipal reliance on revenue generated from traffic stops adds pressure to make more of them. One town, Sycamore Hills, has stationed a radar-gun-wielding police officer on its 250-foot northbound stretch of Interstate.

When you split a metro area into dozens of tiny local governments (St. Louis County, to be clear, doesn’t include the actual city of St. Louis, which spun off from it in the 19th century), they tend to duplicate each others’ services, which is of course extremely expensive. But raising taxes so that each tiny borough can afford its own police and fire department is a nonstarter, since wealthy residents can always just move one town over. End result: You have police departments that self-fund by handing out tickets. And thanks to the delightful racial dynamics of U.S. law enforcement, black residents are disproportionately stopped and accosted, even though police in Ferguson are less likely to find contraband when they search black drivers than when they search whites.

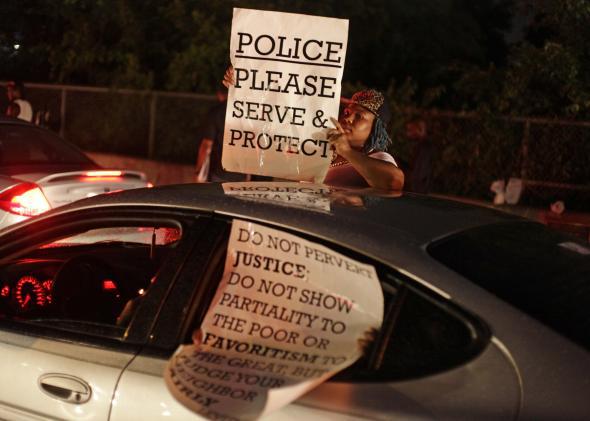

Michael Brown wasn’t being pulled over for speeding when he was shot. But we’re talking about the broader issues that poison the relationship between a community and the cops who are, theoretically, paid to protect them.

In a way, you can think of it as a small-bore version of the problem with civil forfeiture laws, which allow state and federal governments to confiscate property allegedly involved in crimes and which are often accused of encouraging “for-profit policing.” The same way the Justice Department puts the heat on its lawyers to increase forfeiture claims in drug cases—because that’s where they can skim money—local police have every incentive to crank up their traffic stops.

Smith’s solution to the problem is to remerge St. Louis and its nearby suburbs, which will help the metro area feel less fragmented and help give the black community of Ferguson more political power to demand better treatment from police. As I wrote last week, while the city is two-thirds black, its government is mostly white, because the young, poor, and often transient black community has trouble mobilizing votes. In St. Louis, by comparison, the black population has been able to establish stronger civic institutions and exerted more influence. Of the many formidable problems that Ferguson has come to symbolize, we can add for-profit law enforcement to the list.

Read the rest of Slate’s coverage of the protests in Ferguson.