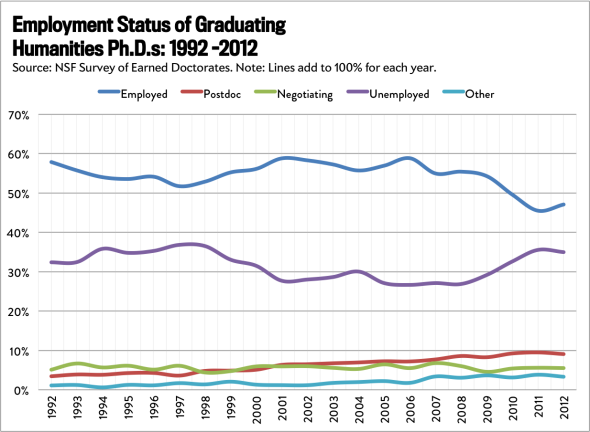

The weak job prospects facing humanities Ph.D.s are sort of a dog-bites-man story by now, and most budding classics scholars probably don’t need another reminder that they may have trouble ever getting a mortgage. But while working on my piece about surprisingly mediocre employment trends among young scientists, I gathered some data that I think uniquely spells out the consistent horror of the humanities market over the past 20 years.

The numbers come from the National Science Foundation’s Survey of Earned Doctorates, which asks Ph.D.s during their graduation year whether they:

- Have a definite job commitment from an employer, whether in industry or in academia;

- Have a definite commitment for a postdoctoral research appointment;

- Are negotiating with at least one organization;

- Are still job hunting (meaning unemployed); or

- Have other plans, such as pursuing yet another degree.

Meanwhile, the NSF uses the label “humanities” broadly, covering foreign languages, literature, philosophy, history, performing arts, and other specialties.

Now on to numbers. The most important line is that purple squiggle, which tracks joblessness. In 2012, the last year available in the data, about 35 percent of graduating humanities Ph.D.s were still seeking work and weren’t negotiating with any potential employers. In happier economic times, the rate was just under 30 percent—certainly better, but still high.

Jordan Weissmann

Even in scientific fields where jobs are scarce, unemployment rates at graduation simply don’t rise that high. Take the life sciences and chemistry. In 2012, fewer than a quarter of new Ph.D.’s in those fields reported that they were employed. Yet outright unemployment among these students was also under 25 percent, because they could still find postdoctorate positions—temporary research posts that let them train under a tenured professor and possibly burnish their resume. They don’t pay especially well, but they offer opportunities for those who can’t find better.

In the humanities, postdocs are far rarer, for the simple reason that literature and foreign language professors usually aren’t running large research labs requiring many pairs of hands. In the end, most grads either find a job, or they find nothing.

Then again, job is a tricky word here. When the NSF asks students whether they have a definite commitment from an employer, it doesn’t differentiate between short-term or part-time jobs and stable, permanent work. In other words, it tosses together adjuncts and teaching fellows along with graduates who end up in the tenure track—meaning the real market might be even a bit worse than this graph lets on.