The word hysteresis sounds as if it should refer to some sort of 19th-century quack medical diagnosis—a recurring version of female hysteria, perhaps. I can just imagine a mustachioed doctor striding into his waiting room to counsel some perspiring husband. “Sir, your wife is suffering from hysteresis,” he would gravely intone. “And the treatment, I am afraid, is quite expensive.”

But no. Hysteresis is, supposedly, an economic malady—the idea that “a deep recession can cause irreparable damage to the economy,” as the Washington Post’s Matt O’Brien has succinctly put it. With America’s recovery still plodding, more economists seem to believe that we’re suffering an acute case of the illness.

Typically, we expect economies to fully heal after a recession. But if a downturn is powerful enough, and its effects are allowed to linger long enough, the thinking goes, a country can end up permanently scarred. The unemployed drift from the workforce for good. Companies cut back on investing in new tools or research, which makes them less productive and innovative in the future. Ultimately, the economy’s potential—its size if everything were functioning normally, judged by fundamentals like labor availability and capital stock—simply shrinks. Hysteresis sets in.

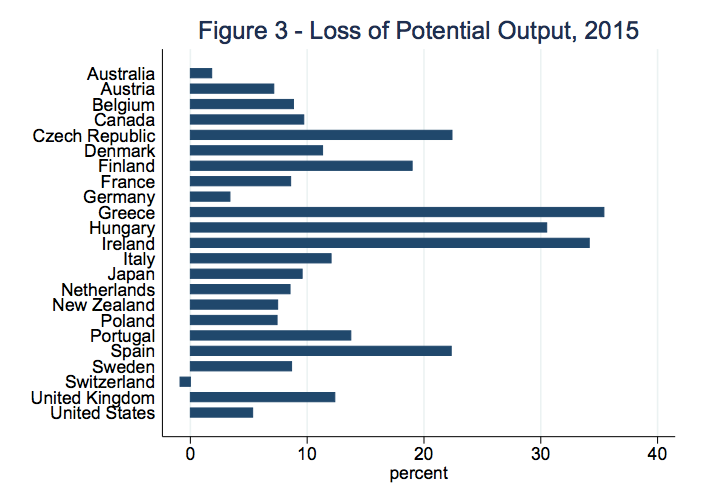

And Americans aren’t the only ones supposedly suffering. Most of the developed world appears to be infected, too. Recently, Johns Hopkins economist Laurence Ball released a working paper looking for signs of hysteresis across 23 countries in the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Based on forecasts for 2015, he finds that the loss of potential economic output comes out to about $4.3 trillion. “The total damage from the Great Recession,” he writes, “is slightly larger than the loss if Germany’s entire economy disappeared.”

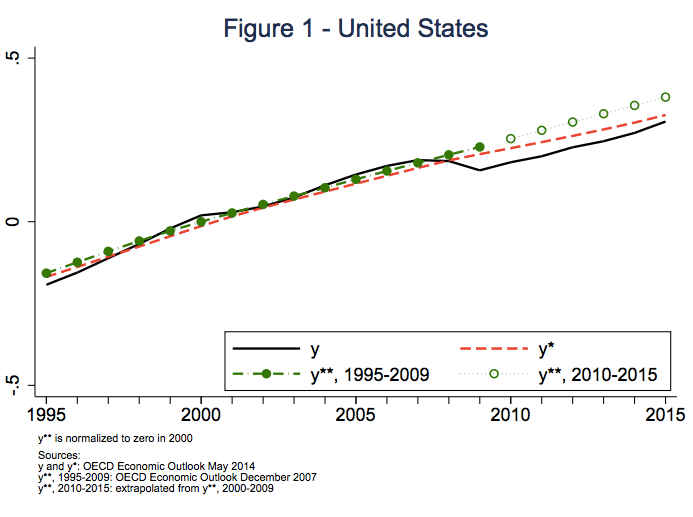

Here, for reference, is how the U.S. evolution looks over time. The green circles show the growth trend for our potential output prerecession. The red line shows the lower-postrecession trend. The black line is what the economy is actually producing. As you might notice, we’re still failing to grab that lower bar.

Now here’s how much potential output each of the 23 countries may have lost, in percent terms. Greece, of course, has it worst, because it’s Greece—by 2015, 35 percent of its economic potential will have evaporated. Only Switzerland came out completely unscathed.

The big question economists are now debating, as Ball writes, is whether hysteresis can be reversed. Some believe that once an economy falls off its old track, it can never really return. For instance, they would argue that a giant recession will cause labor force participation to shrink more than a hiring boom will cause it to grow. We’re going to be poorer, forever more—and no amount of stimulus from Congress or from the Fed will help.

Others believe this is quack analysis. As Paul Krugman has written, the common models used to forecast potential GDP take it for granted that if an economy doesn’t bounce back quickly from a recession, it’s because something has been fundamentally damaged, rather than because the government offered up an insufficient policy response. So stats showing our lost potential might just be the product of bad assumptions and self-fulfilling prophecy. Even if the recession did damage our economy’s foundations, Jared Bernstein argues we still might be able to fix them with enough stimulus. “If you can bend the [growth] trend you can mend the trend,” he writes.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem like our policy makers are ready to try any experimental cures. For now, we seem destined to plod along.