New college grads may be facing dizzyingly high unemployment this commencement season, but MIT professor David Autor believes we still don’t have enough of them. The famed economist is out with a new paper in the journal Science that aims to remind the world that while much of the inequality debate has focused on the rise of the top 1 percent, the biggest—and arguably most important—change in America’s income distribution has been the widening gap between those with and without college degrees.

“We have too few college graduates,” Autor told the New York Times’ David Leonhardt. If we had more, he argues, the income gap would shrink.

Helping more Americans graduate from college is a worthwhile goal (emphasis on the word graduate; too many already attend and drop out). Everybody deserves their personal shot at a healthy career and financial life, and higher education is often the best path to those goals. But flooding the job market with graduates, as Autor seems to advocate, has always struck me as an odd and maybe counterproductive approach to tackling inequality as a broad economic issue.

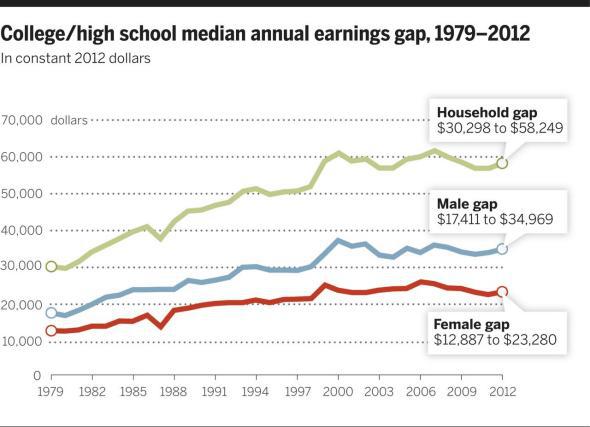

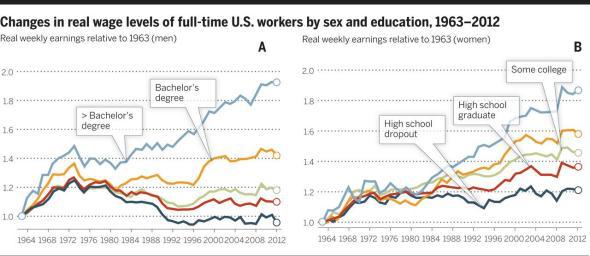

As Autor writes, the relative value of a college degree rose over the past several decades thanks to a handful of trends. First, wages of high school–educated men collapsed, as inflation ate away at the minimum wage, factory jobs disappeared, and unions went into decline. At the same time, the growth of America’s college-educated population slowed down even as demand for graduates grew, thanks in part to the rise of high-tech industries and the digitization of the economy. As a result, wages jumped for bachelor’s degree holders.

But recent research suggests that corporate America’s hunger for brain power—or “cognitive skills,” as economists like to put it—began to decline around the time of the dot-com bust. College graduates aren’t quite the hot commodities they were during the Reagan and Clinton years. Going to school is still, on average, a very good deal. But as Autor’s own graphs show, wages have flat-lined for bachelor’s degree holders, even as they’ve continue to climb for Americans with advanced degrees. And while the extent of underemployment among college graduates is often exaggerated, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York has found that a growing percentage of them are working in jobs that don’t require their degree and pay less than $45,000 a year. Chances are, many of those underemployed B.A.’s and B.S.’s are taking career opportunities from less-educated workers who could desperately use a leg up in the economy.

To make a long story short, unless the overall job market is booming, simply churning out more college graduates risks making everybody a bit poorer.

Of course, there are counterarguments. For instance, even in jobs that don’t traditionally require a bachelor’s degree, employers tend to pay college-educated workers more generously, because they’re more productive. A better-schooled workforce, therefore, might theoretically turn into a better-compensated workforce, since an infusion of college graduates would plump up wages in some traditionally low-pay industries. But that’s a giant hypothetical that assumes companies have a limitless appetite to pay up for higher quality talent. And even if that were the case, it wouldn’t necessarily close the gap between college-educated adults and high school diploma holders. In fact, it might make it worse, as career opportunities for high school grads dried up.

Some employers might also argue that the U.S. is suffering from a “skills gap” that is preventing them from hiring, and which more education would fix. The problem is that most of the industries making that claim tend to be middle-skill jobs that require an associate’s degree. Moreover, the evidence behind their complaints is rather lacking.

It’s also important to remember who would stand to lose the most if a surge of graduates did manage to bring down the college premium. Chances are, alums of elite schools wouldn’t be particularly affected, since any substantial growth would likely come from mid- and lower-tier schools. Graduate degree holders, the real winners of the educational race of the past 30 years, also wouldn’t be much affected. In the end, you’re essentially talking about an approach to inequality that involves bringing solidly, if unspectacularly, middle-class households a little closer to the bottom, while pushing down the bottom even deeper.